For children growing up in turbulent households the outcomes are stark. Young people in receipt of social care attain drastically lower than average GCSE grades, have an increased chance of suffering poor physical and mental health and, worryingly, are more likely to have offspring who endure a similarly detrimental childhood.

Social services play a crucial role in improving these outcomes but there is still limited evidence on what works to best help parents meet the needs of their children. That is why the Department for Education (DfE) commissioned the Social Work Innovation Programme in 2013, and required the projects be rigorously evaluated.

Our evaluation of one such project, Project Crewe, has just been published by the DfE. We’re proud to have contributed one of the first successful Randomised Controlled Trials in this field.

What is the project?

Project Crewe is an intensive early intervention for children on the first rung of statutory social support, delivered by non-social work qualified staff who are managed by social workers and supported by volunteers.

What distinguishes the project is its more personalised and frequent support offered to families using a solutions focussed approach. On top of visiting families three times more frequently than in traditional models, Family Practitioners worked with the individuals to identify their issues and strengths.

Our trial randomly allocated 132 families, comprising 326 ‘children in need’ (CIN), to either receive normal social worker support, or the revised Project Crewe model. We then measured the number of cases resolved, and rate of re-referral over a twelve month period.

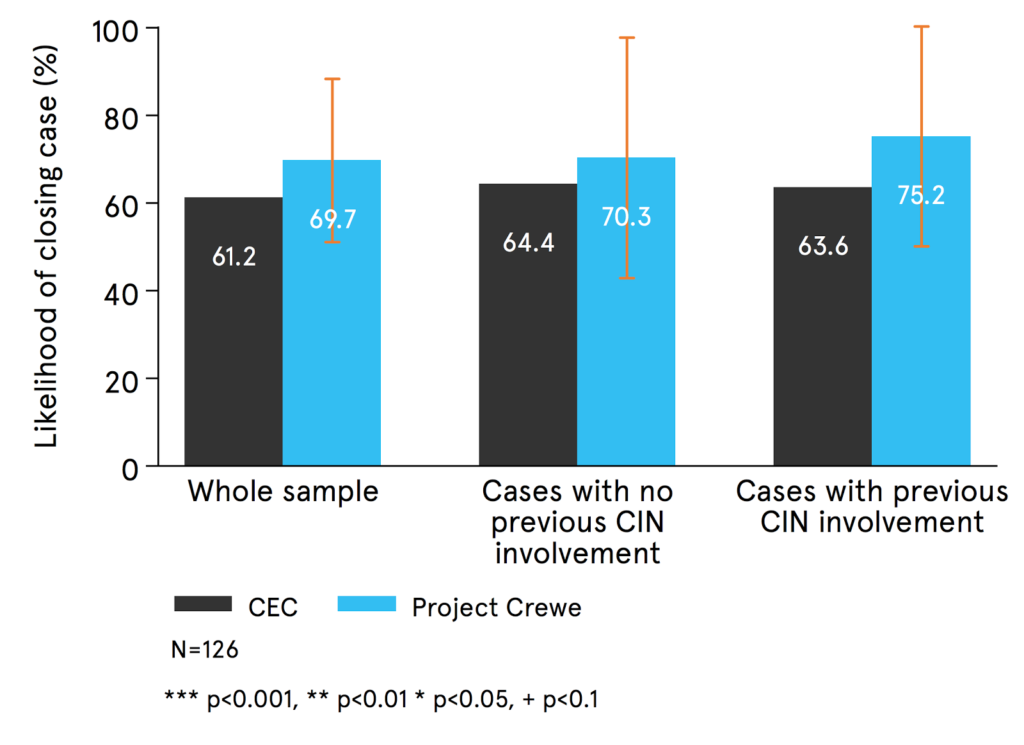

Figure 1: Likelihood of closing cases

What we found

Our results provide promising indications of impact:

- More CIN cases were resolved through Project Crewe than those cases which remained with the local authority, although cases that remained with the social worker model were on average resolved quicker.

- Project Crewe appeared to increase the number of protective factors, (such as supportive wider family, parental employment, good school attendance) around the family – which correlate with a decreased risk of harm reoccuring.

- Project Crewe was most effective for families with a history of social care – resolving 12 more than the social worker model per 100 CIN cases of this type.

It’s important to note that these results are not conventionally significant. But for these families with a history of social care, the more intensive approach offered by Project Crewe could offer benefits to families, communities and local authorities. This finding is supported by the qualitative evidence where families felt the programme offered them a ‘fresh start’.

Janine*, a mother of 5, who had multiple social workers before being allocated to Project Crewe, spoke about her positive experiences:

‘ ..Within 3 weeks when Project Crewe came in my confidence changed. They said, “Right we know you’re a good mum, what do you feel you can do?” and I said, “I can do this and this,” and it was the way that they spoke that was totally different. The first two social workers I couldn’t get to know. Whilst Project Crewe came at it in a good way, they could see we were good people.’

Speaking to families who experienced both Project Crewe and the social worker model helped us understand which elements of the intervention were particularly beneficial.

In interviews with 15 families and their support worker we found that the solutions-focused approach taken by Project Crewe reframed how support was offered: from the outset families identified their own issues and strengths as opposed to being told what needed change.

This collaborative approach, coupled with frequent personalised visits and the use of feedback tools, appeared to help families monitor their own progress and take ownership of their problems. Jemma*, mother of 3, describes below:

‘They asked me what I wanted. It sounds silly and small but they were thinking about what I needed, not what they thought I needed. It makes a massive difference because I want to work with them and I can see us getting somewhere, getting actually to an end and actually getting to a place where the house is calmer.’

What next?

Despite this report providing insights into how to support families, it should be most influential for its novel methodology. Our innovative RCT should pave the way future experimental evaluation of children’s social care interventions.

Although large scale RCTs pose many challenges to design and implement, it’s society’s most vulnerable young people who will benefit from an increasingly robust evidence base in the children’s social care sector.

*names have been changed to protect identity