Almost half of the UK population will get cancer during their lifetime. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical for improving cancer survival rates and quality of life, yet one in five cases of cancer is still detected late through emergency hospital admissions. The national cancer screening programmes (breast, cervical and bowel) are designed to catch cancer at an early stage.

In Greater Manchester (GM), whilst cancer rates are higher than the national average, the uptake rates for invitations to each of the three cancer screening programmes are lower than the England average. Greater Manchester Health and Social Care (GMHSC) Partnership asked BIT to look at this issue. Between March 2016 and August 2018, BIT ran a field trial testing ways to improve breast cancer screening uptake and 2 online trials which focused on cervical and bowel cancer screening. Thanks to the ambition of GMHSC Partnership, without whom this work would not have been possible, BIT got a unique opportunity to rigorously test a full range of interesting behavioural approaches to improving screening uptake. We learnt a lot about how England’s screening programmes work, how different groups feel about screening – and crucially, what works and what does not to increase screening rates.

Breast cancer screening

Our first trial was a large field experiment (~45,000 women) testing changes to the invitation letters for routine breast cancer screening appointments. Through the NHS screening programme, all women aged 50 – 70 registered with a GP are invited for a mammogram every 3 years. Attendance rates are slightly lower in GM compared to the national average. Research suggests that lack of time, fear, pain and embarrassment are what stops some women getting screened.

Our letters

We tested 2 new versions of the invitation letter. Both were simplified compared to the existing letter and included a tear-off slip with the time and date of the appointment printed on it (to act as a reminder). In BIT’s Australian breast cancer screening trial, the tear-off slip increased women’s screening attendance by 17%.

We tested two messages:

A ‘cost’ message

‘Every missed appointment costs the NHS approximately £75’

Evidence: People can be twice as sensitive to a loss than an equivalent gain. We previously found that informing people about the cost to the NHS of missed hospital appointments helped to reduce the number of people not turning up by 25%.

A ‘deadline’

‘We are only offering women from your GP practice appointments at [address of local screening hub] for the next few weeks. Don’t miss your chance to get screened close to home.’

Evidence: When we think something is scarce, we value it more and are more likely to prioritise it. Such time limitations not only strengthen this scarcity effect but can also help overcome procrastination.

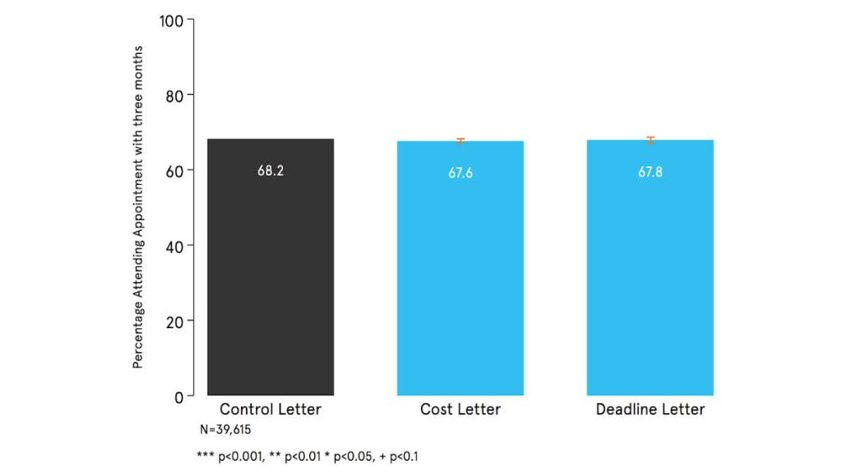

Results

In this trial, we found no difference in screening rates between any of the different letters. We were surprised by the result, because the approaches we used have been successful in previous trials. This result highlights the importance of testing and we are sharing the results here to help inform other people’s work.

Cervical cancer screening

We used our Predictiv online platform to run an online experiment with 1,800 young women aged 24 – 30. Our aim was to test how different messages influenced their willingness to complete cervical screening. It is important to point out that this work was done online and so measures stated behaviour. This means we were asking women whether they planned to attend their cervical cancer screening in future rather than measuring whether they were screened.

Young women (25-29) have the highest incidence of cervical cancer, yet are less likely to get screened than women in other age groups. The most common barriers to cervical screening uptake are embarrassment, inertia and forgetfulness, fear of pain, and fear of a positive result. Embarrassment is a particularly big issue for young women. There are also some common misperceptions about cervical cancer e.g. that the HPV vaccination provides full protection from developing cervical cancer, or that cervical cancer affects mostly older women.

Our messages

We tested the 3 messages, which were added to the top of the standard screening invitation letters:

Enhanced active choice

We gave participants the following options:

‘I will book my appointment today by calling my GP practice.’

‘I will not get screening and will miss out on the chance to reduce my risk of developing cervical cancer.’

Evidence: Presenting people with a list of options with their consequences can help to counter omission bias (i.e. the perception that inaction is less harmful than action with the same outcome). This approach has helped increase flu vaccination rates.

Loss and gain frame

‘Prevention-gain’ message

‘Cervical cancer screening prevents cancer by identifying early changes in cells. Getting screened hugely reduces your risk of getting cervical cancer.’

Detection-loss message

‘Cervical screening can help detect and remove cells which could develop into cancer. If you don’t get screened you will be in the group of women who are much more likely to die from cervical cancer.’

Evidence: How we frame health behaviours can influence their uptake. Previous studies have shown that framing health behaviours in terms of losses works better for detection and framing them in terms of gains is better for prevention. Cervical screening could be framed as both: it can detect an existing condition but also reduces chances of getting cancer. So we tested both.

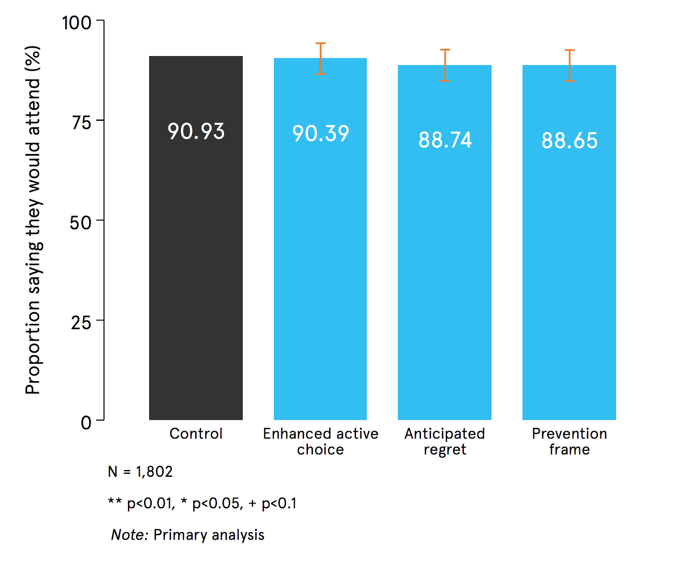

Results

There was no significant difference in the proportion of women who said they would get tested in all the groups. We don’t know why this is, it may be that our messages did not address the barriers of physical discomfort and embarrassment. This result could also be, in part, because the trial only measured intended rather than actual behaviour. In our trial, 90% of young women said they would get screened, whilst only 65% do so in real life.

Bowel cancer screening

We also used our Predictiv platform to test our ideas for bowel screening. We ran an online experiment with 1,600 participants aged 55 and over (to reflect the NHS bowel cancer screening programme’s targeting). As with the cervical trial, it is important to note that the results here related to people’s stated intention to complete screening rather than their actual behaviour.

Unlike screening programmes for other cancers, the bowel cancer screening test is completed at home by the individual. Although this makes the process somewhat easier, the test requires people to collect 3 stool samples which then need to be sent for analysis. Bowel cancer screening rates, both in England and in the Greater Manchester Area are low (59% and 57% respectively in 2016/17).

There are a number of reasons people give for not completing the bowel cancer screening test. The most commonly mentioned are embarrassment and disgust but fear of positive result and fatalism also play a part; particularly among the BME population and lower socioeconomic groups.

Our messages

We tested 3 messages compared to the current invitation letter:

Certainty effect

‘Bowel cancer symptoms can be difficult to spot. Use this opportunity to get some peace of mind.’

Evidence: We know that people dislike uncertainty more than being certain about the worst possible outcome so we created a message to try and encourage people to reduce uncertainty.

Anticipated regret

‘If you were diagnosed with bowel cancer, would you regret not having taken the early detection test?’

Evidence: Loss framing has been shown to help prompt behaviour which detects health conditions. We also prompted people to think about the regret they might feel if they missed the screening opportunity. This approach has shown some promise for increasing HPV vaccinations.

Consistency

‘Would you want your family or friends to do the screening? Set an example by doing the bowel cancer screening yourself.’

Evidence: People can experience discomfort when their attitudes and behaviours are inconsistent (known as ‘cognitive dissonance’). We tried to prompt dissonance by getting people to think about what they would encourage family and friends to do (even if they might not have done the screening test yet themselves). We then gave people a way to resolve the inconsistency by suggesting they could complete their bowel screening.

Results

The anticipated regret message was the most effective: compared with the control group it significantly increased people’s willingness to get tested by around 10%.

In our analysis, we also looked at people’s perceptions of bowel cancer: our participants overestimated the likelihood of getting cancer and underestimated the survival rate. This matters because fatalistic attitudes about cancer are correlated with lower intentions to get screened.

To our knowledge, this piece of work is novel in cancer screening in terms of the numbers of people in the trials. In funding these trials testing the impact of behavioural messaging, Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership took an innovative approach to evidence based policy making. We are sharing these results to inform future work, both in Greater Manchester but also in the UK and the rest of the world.