I keep six honest serving men (they taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When and How and Where and Who.

– Rudyard Kipling (1902), Just So Stories

A brutal murder, an ingenious bank robbery, the latest Scandi crime thriller – few things capture our imagination as forcefully and persistently as crime. At the heart of this fascination lies our deep desire to understand why crime happens – and how to prevent it.

How we go about countering crime depends on the theories we hold on why it occurs. At the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) we are fascinated by the varied forces that shape human behaviours such as crime. In this series of blog posts, we share some of what has influenced our thinking on crime: why it matters and what we know (#1), why it happens (#2), and how to prevent it (#3).

The true cost of crime

Crime can destabilise neighbourhoods and destroy lives. It is estimated that crime in the UK costs society £60bn every year, which is nearly half of the budget for the NHS in 2018/19 (i.e. pre-covid) and one-and-a-half times the core school budget of £42bn. Imagine if we could wipe out crime and spend that money elsewhere in our economy. Or imagine, we could spend money elsewhere in order to prevent crime.

In order to prevent crime we need to understand it, and before we tackle the vexed question of why people commit crimes, there are some more basic questions we can answer. Preventing crime is an inherently empirical exercise: to understand it we need to ask where and when and what kind of crime occurs, how it is conducted and who perpetrates or is victimised by it?

Crime and the city – Facts not fiction

In recent work, BIT supported the London Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) in drawing on empirical evidence and rigorous research methods to test hypotheses about crime. The London VRU was set up in 2018 to both reduce violence in the short term as well as to analyse underlying causes and coordinate communities and public organisations to address them in the long run. In a first report, BIT and VRU looked at crime in London. Here we found out a few keys facts that could help us understand criminal behaviour in the UK capital such as:

- Violent crime in London alone cost £3 billion in 2019.

- Contrary to a stark increase in media reports of violence – crime did not increase between 2013 and 2017 in the majority of London’s neighbourhoods (see the discussion here).

- Crime is highly geographically concentrated, which is starkly illustrated in another project BIT were involved with as well as in one of our other blog posts.

- As in other cities, crime and deprivation tend to vary in London – both geographically and over time. Between 2013 and 2017, for instance, violence decreased in many neighbourhoods while substantially increasing in just six (i.e. fewer than 1 per cent).

- Reductions in police and criminal justice capacity e.g. the drop in front-line police officers by 10% from 2010 probably made it more difficult to disrupt and deter violence.

- Non-crime demands on police stretched officers’ time even thinner, also making it more difficult to do preventive work, such as building relationships in vulnerable communities.

- Key indicators of police effectiveness have deteriorated: Between 2014 and 2019, sanction detection rates for knife crime and charge rates for violent offences have halved from 27% to just 13% and from 15% to just 8%, respectively. Homicide detection rates have fallen, too.

- Public perception that the police can protect them has worsened in parallel – the share of Londoners seeing knife and gang crime as a problem locally has increased by ~5% in recent years.

- While there is evidence from some cities that greater community trust and cohesion are connected to lower levels of violence, this hasn’t been found in London. This could be due to the fact that neighbourhoods with high trust and cohesion often exist in close proximity and overlap with deprived areas with higher violence rates, complicating clear-cut measurement of how the one relates to the other.

To get a better understanding of crime from all this information, let’s zoom in a bit. Below is a map of violent crime in Lambeth, South London. What we observe is a pattern repeated across London: year-on-year increases in crime are confined to a small number of areas – usually those where violent crime was already relatively common. Moreover, crime rates fell in many, often adjacent, parts of the borough over the same period. What this tells us is what we know already, crime is localised and concentrated in some places more than others. This holds true even if we use other measures of violence (like ambulance data).

(Source)

The geographical concentration of crime is observed all over the world so consistently that the phenomenon has been declared ‘the law of crime concentration’ (see this recent paper on homicides in Latin America). What’s really amazing is that it’s possible to observe ‘hotspots’ of crime down to the street level. In London, for instance, bus stops appear to be a particular crime-prone location that make them amenable to crime prevention.

So what?

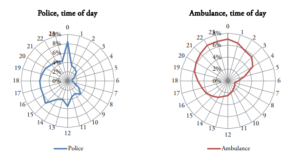

Well, if we know where crime occurs that’s a piece of information we can use to help prevent crime. But this knowledge is even more potent when coupled with what we know about when crime occurs. We see spikes in violence at times when people are mixing such as when schools finish and when pubs [remember them?] close. With these two pieces of information we can already work to prevent crime — by having resources in places to respond when crimes occur, but also to proactively plan to minimise/avoid situations that might lead to crime — without getting into questions about why people commit crime.

(Source)

We can send more police to places and that will reduce crime. Numerous studies of ‘hotspots policing’ illustrate this (and similar work has been done on suicide hotspots – not with police as the interventionist – but it again speaks to the idea of human behaviour predictably clustering in time and space) – but as police chiefs often say we ‘can’t arrest our way out of a crime problem’. So we need to think about how to prevent crime, both ‘in the moment’, and before people view crime as a viable alternative.

Data and evidence are paramount if we want to mitigate and prevent crime. We must zoom in to investigate the conditions and contexts under which crime occurs, develop and deepen the existing evidence base, and use these insights to develop interventions. The other blog posts of this series look a bit more into the nitty-gritty of a behavioural approach to crime – both understanding criminal behaviour, and what we need to address and prevent it.