In Part 1 of this blog post series, we talked about the behavioural barriers that migrant domestic workers (MDWs) face when deciding whether and how to seek help, and the prototypes that we designed to address these barriers.

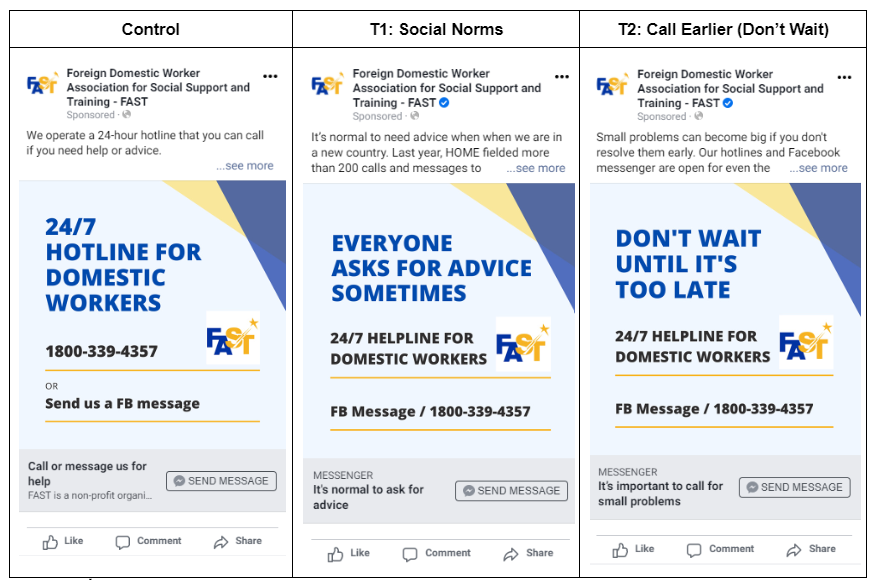

If you had voted in the poll in our last blog post, a big thank you to you! You need wait no longer for the results: we eventually tested the Social Norms and Call Earlier (Don’t Wait) Facebook advertisements against a simple informative control.

Each advertisement was translated into five languages commonly used by migrant domestic workers (MDWs) in Singapore (Bahasa Indonesia, Tagalog, Burmese, Hindi, and Tamil). Using Facebook Advertisements, we trialed the advertisements with a total of 45,000 Facebook users, targeting female users in Singapore based on their age and the language in which they used Facebook.

Each advertisement was translated into five languages commonly used by migrant domestic workers (MDWs) in Singapore (Bahasa Indonesia, Tagalog, Burmese, Hindi, and Tamil). Using Facebook Advertisements, we trialed the advertisements with a total of 45,000 Facebook users, targeting female users in Singapore based on their age and the language in which they used Facebook.

The objective of running a Facebook advertisements trial was two-fold:

- Firstly and primarily, to examine what behavioural principles are most effective at encouraging MDWs to send the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) a message to ask for advice.

- Secondly, to reach out to MDWs who have no existing links with NGOs. While FAST and HOME rely heavily on word-of-mouth recommendations and referrals by volunteers, these methods are most effective at reaching MDWs who already have established networks in Singapore. It is equally (if not more) important to explore and test alternative methods to reach out to MDWs who do not have such social connections, as they may be even more vulnerable.

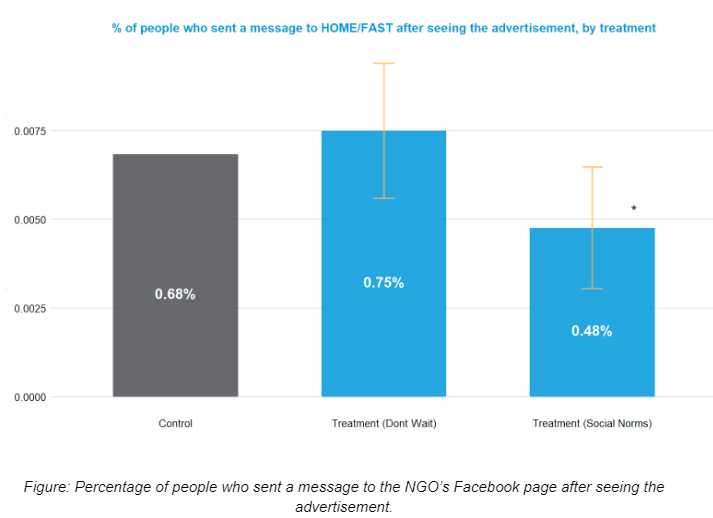

A surprising finding: Users who saw the Social Norms ad were less likely to message the NGO or click on the ad

The Control and Don’t Wait messages seemed similarly effective in prompting people to send messages to the NGOs. However, people who saw the Social Norms message were less likely to send a message compared to people who saw the Control message.

The Control and Don’t Wait messages seemed similarly effective in prompting people to send messages to the NGOs. However, people who saw the Social Norms message were less likely to send a message compared to people who saw the Control message.

This was particularly surprising to us, as we had found in our fieldwork that social support was the strongest facilitator for help-seeking. Some reasons the Social Norms message might not have worked as well might be: (i) the message might not have been urgent enough for people to click on the ‘Send Message’ button directly; (ii) “everyone” asking for advice might have been too broad, causing users to identify less with the social norm of asking for advice; (iii) having specific prompts (e.g., call Organisation X when y event happens) is an important precursor to seeking help, so “[asking] for advice sometimes” is not specific enough for people to take action.

Despite these counter-intuitive findings around the Social Norms message, we would not discount future social norms-based messages entirely. As social support came out so strongly in our fieldwork, we believe it is still worth exploring social influence messages and interventions; however, the phrasing of the messages should be refined and tested carefully.

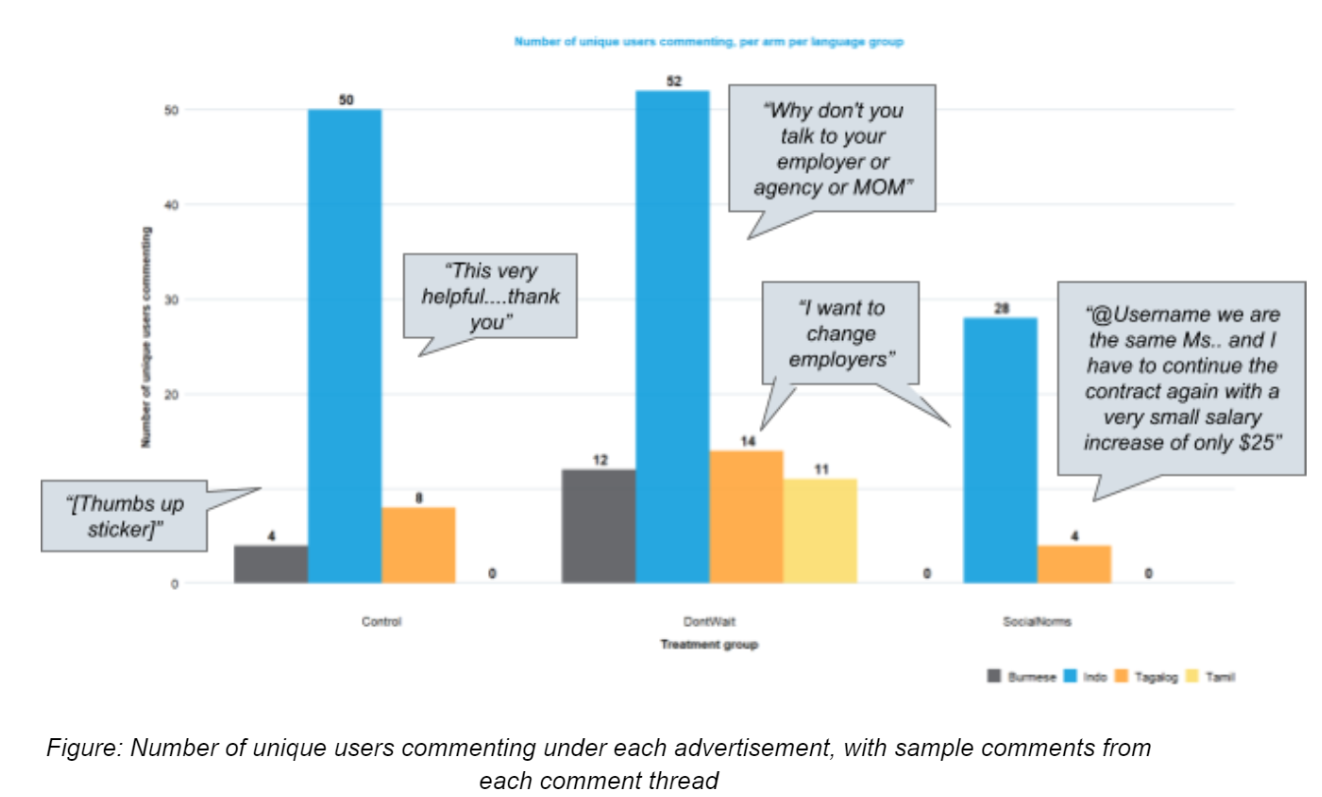

We recommended scaling the “Don’t Wait” arm as it prompted the most discussion in the Comments section

In addition to the number of clicks and messages sent, we also qualitatively analysed the comment threads associated with each of the advertisements. We found that the “Don’t Wait” arm prompted the most discussion in the Comments section while the Social Norms advertisement generated the fewest.

Analysis also showed that comments for the two Treatment arms were qualitatively different from comments for the Control arm.

The Don’t Wait and Social Norms advertisements seemed to generate comments that were more dynamic and interactive — some people left comments asking for help (“I want to change employers”), while other commenters offered advice (“Why don’t you talk to your employer or agency or MOM”; “Make sure you get the employer’s signature if you want to transfer”) and support (“There’s a number listed there… you can Whatsapp”). Comments under the Control advertisement, on the other hand, were more basic: the vast majority only said “Thank you” or left various encouraging stickers.

The Don’t Wait and Social Norms advertisements seemed to generate comments that were more dynamic and interactive — some people left comments asking for help (“I want to change employers”), while other commenters offered advice (“Why don’t you talk to your employer or agency or MOM”; “Make sure you get the employer’s signature if you want to transfer”) and support (“There’s a number listed there… you can Whatsapp”). Comments under the Control advertisement, on the other hand, were more basic: the vast majority only said “Thank you” or left various encouraging stickers.

Having more people offer advice and tag their friends in the comments section is generally a good thing. As we saw in our fieldwork, community support can be hugely beneficial, especially to people who have not accessed formal help-seeking services before. While there will always be risks when comments sections are open to the public (e.g., factual errors in advice, unhelpful or discouraging comments), we found that the helpful comments far outnumbered the few unhelpful ones.

As a result, we recommended scaling the Don’t Wait message in order to encourage MDWs to support each other in the community.

Besides the message itself, what else did we learn from this trial?

1. Promoted social media posts appear to be a good complement to existing outreach methods through volunteer networks.

While we tested our messages using Facebook advertisements, anecdotal evidence suggests that exploring other social media and chat platforms (e.g., WhatsApp, TikTok) could be equally productive. We also need not be limited to static text or pictures — voice and short video are also promising media, especially for MDWs who are less fluent readers.

2. Messages to encourage help-seeking should be as specific as possible.

Many of the barriers around help-seeking relate to uncertainty — uncertainty about what kind of situation warrants help-seeking, what the appropriate level of help-seeking might be, and above all, about the consequences of help-seeking. As such, messages which provide clear and precise messages are likely to be mostly helpful. Evidence from our trial furthers this point, as a vague-sounding Social Norms message performed worse than a simple advertisement that informed people directly about the availability of the helpline.

3. The best way to design for a specific target audience is to involve them at every step of the process.

In this project, we made sure we involved MDWs at each step of the process– we worked with volunteer MDWs translators while conducting fieldwork interviews and to co-design messages, and we also sought feedback from MDWs on the prototypes before choosing the final messages to trial. Their involvement greatly improved this project’s outcomes, all the way from making interviewees feel more comfortable speaking to us, to helping each other on the comments section of the Facebook advertisement interventions.

We would like to express our gratitude and thanks to Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) and Foreign Domestic Worker Association for Social Support and Training (FAST). Not only have they been excellent partners to work with, more importantly, they do invaluable work to support MDWs to work successfully and safely in Singapore.

Find our full final report here.