In the wake of the #MeToo movement, many organisations and universities are searching for evidence-based strategies to combat sexual harassment.

Encouraging bystanders, those who witness or hear about sexual harassment, to take action is a promising way to do this.

When bystanders take action, they protect and support the person targeted, discourage the perpetrator, and show that sexism and sexual harassment are not acceptable in any setting – whether a workplace, a university campus, or the broader community.

The challenge is that although many people want to intervene when they witness these behaviours, most fail to do so. Research by the Australian Human Rights Commission found that 1 in 4 students reported being sexually harassed in Australian university settings in 2016, but only 20% of bystanders in these situations reported taking any action. Inaction can be due to fear, anxiety, concern about what others would think, and lack of skills and confidence.

Exciting new findings from The Behavioural Insights Team show that it is possible to help bystanders overcome these barriers and take action. In our work with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, we partnered with two universities and carried out trials to see whether behavioural insights can empower more people to take action against sexism and sexual harassment. A summary of our results can be found here, along with tools and guides for running your own bystander action campaign.

Our intervention tested a number of messages to encourage people to take action after witnessing sexism and sexual harassment.

We sent a series of five behaviourally-informed emails to just under 30,000 staff and students. These provided specific advice on how to take action. We called this the ‘knowhow’ element of the intervention.

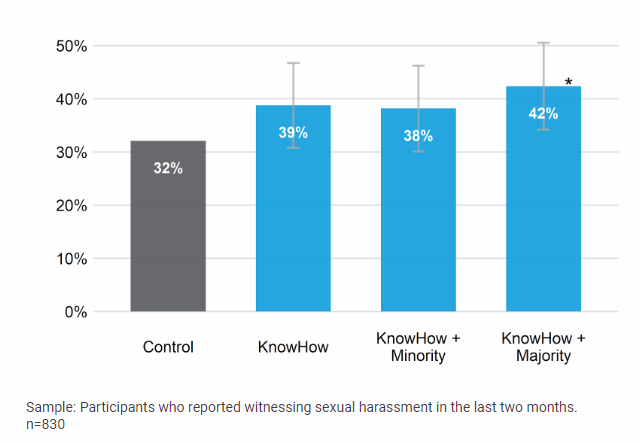

We added two different types of social norms messages to the knowhow text to see if it would boost the impact of the emails. Recipients either saw a ‘majority norm’ message, for example: “Most of us studying on campus think it’s right to call someone out for making sexist jokes or comments … And 78% said they themselves would intervene if they saw sexism and sexual harassment on campus”, or a ‘minority norm’ message, for example: “Most of us studying on campus think it’s right to call someone out for making sexist jokes or comments … But only 46% of us actually do”.

We compared these new messages to a control group who received no emails. The results showed that people who received the majority social norms messaging were more likely to take action against sexual harassment compared to the control group.

Figure: Rates of active bystanding after witnessing sexual harassment in the previous 8 weeks

We also looked at the impact of the messages on sexist behaviours. For women, those who received social norms messaging were also more likely to take action against sexist behaviours. We defined sexist behaviours as making assumptions about a person’s abilities or attitudes based on their gender; responding differently to the same behaviours when they are exhibited by women and men; or making sexist comments or jokes.

Interestingly, the email series’ were not effective at encouraging bystander action against sexism among men. We found that men were also less likely than women to notice sexism and sexual harassment, and less likely to recognise them as requiring intervention. Future initiatives targeted at encouraging men to take action against sexism could focus more deeply on explaining what sexism is, how to identify it and why it’s problematic; and use social norms or messengers from groups that men are most likely to identify with.

We learned a number of important lessons during this work, which will be valuable for others looking to combat sexual harassment.

Firstly, it’s crucial to design messages that fit your specific context. We’ve provided a number of toolkits for different contexts here, but it is important to make sure that they are fit for your organisation. Co-designing your intervention materials with your target audience is key, and it’s also important to test out different messaging to see what works best for different cohorts. Secondly, when you are evaluating your intervention, do so by measuring behaviour change, not just people’s intentions to take action. Decades of research has shown that people’s intentions to act were not good predictors of taking action.

Next up, we will be working with Victorian workplaces to encourage bystander action among staff. Get in touch – info-aus@bi.team.

Want to learn more about how behavioural science can help tackle sexual harassment? Check out our BX2019 Session on combatting sexual harassment including talks from Dr Tiina Likki and Dr Iseult Cremen of BIT and Professor Betsy Levy Paluck of Princeton University.