New results published in the Singapore Macroeconomic Review

Central banks around the world want to know how people expect prices to change.

Why does it matter? Suppose I want a new television. If I expect the price of that TV will be higher next year, I might choose to buy it immediately. I might even borrow money rather than wait until I have enough in my savings account.

Some of the most important financial decisions we make can be influenced by my expectations about how prices might change – should I make a lump-sum payment into my mortgage? How much should I ask for in wage negotiations?

When aggregated across the economy, the answers to these price-related questions influence prices themselves.

An increase in the overall level of prices is known as inflation. Central banks can use our ‘inflation expectations’ to try to predict our financial behaviour. Doing so can inform policies such as interest rate changes or quantitative easing.

But there is a problem. Most people find it quite difficult to answer questions like:

“Based on your own opinions and what you seen and heard, which of the following ranges best describe the 12-month ahead yearly overall inflation rate?”

I’ve spent many years studying and using economics, but I certainly don’t think about my own answer to this question on a regular basis. Some people may not have a good idea of what inflation is, or perhaps aren’t sure whether house price changes should be included or not.

The exact wording of the question and the answer scheme can also be relevant – there are numerous examples from academic studies where changing the way questions or statistics are ‘framed’ changes the response. For example, people gave very different answers about how they sent a tax rebate when researchers described it as “withheld income” as compared to “bonus income” (Epley et al., 2006).

Perhaps for these reasons, the ‘inflation expectations’ generated by these surveys are typically very high. That leaves policymakers with a choice: either to assume that people always expect prices to rise faster than professional forecasters; or perhaps instead investigate whether changing the questions might provide better data.

The latest edition of the Singapore Macroeconomic Review includes new results from a recent experiment to test just that. We worked with Aurobindo Ghosh of Singapore Management University and the Monetary Authority of Singapore to create a new survey.

We found that the way the question and answer are written matters a great deal – especially varying the range of suggested inflation changes.

For responses to the question above (“Based on your own opinions and what you seen and heard, which of the following ranges best describe the 12-month ahead yearly overall inflation rate?”) we changed the possible answers from (the control group):

- Less than 0%

- 0% to less than 2%

- 2% to less than 4%

- 4% to less than 6%

- 6% to less than 8%

- 8% to less than 10%

- 10% or more

- No idea

To (the treatment group):

- Less than 0%

- 0% to less than 6%

- 6% to less than 12%

- 12% to less than 18%

- 18% to less than 24%

- 24% to less than 30%

- 30% or more

- No idea

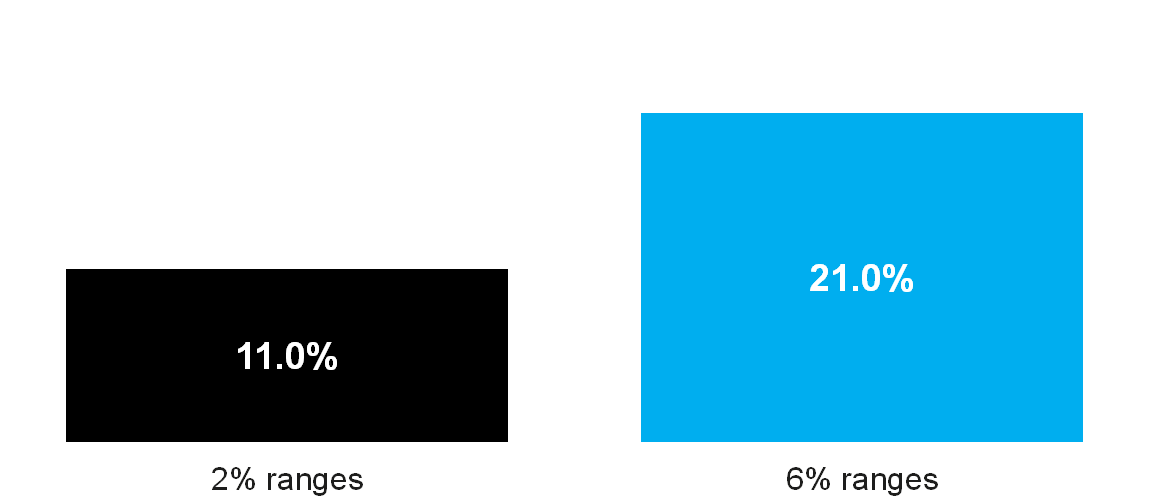

In the control group, one in ten people thought inflation next year would exceed 6%. In the treatment group this doubled – more than one in five. Bear in mind that current inflation in Singapore is around just 0.5% – the last time there was a jump in excess of 5% was the 2008 global financial crisis.

Figure 1: Proportion of respondents predicting inflation >6% next year

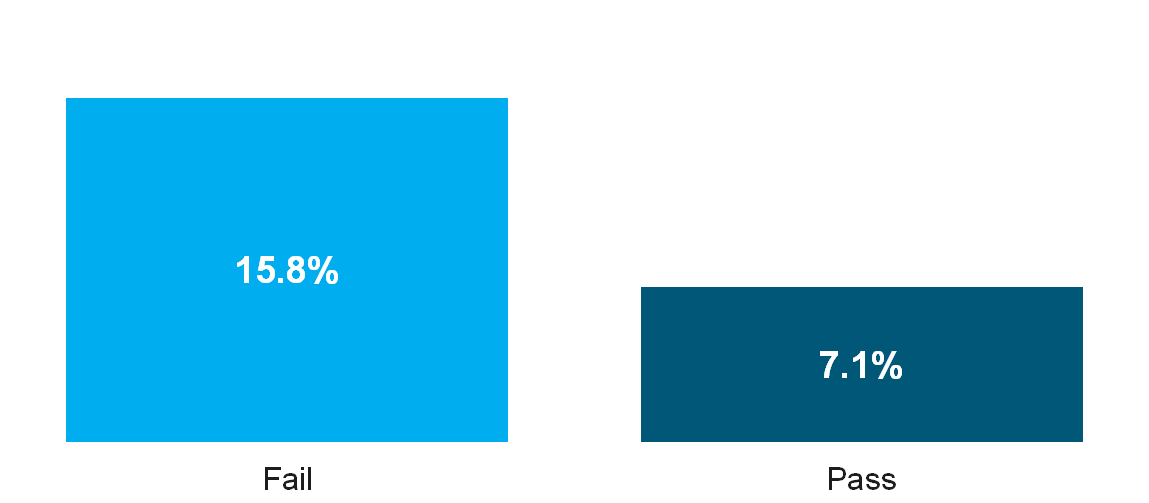

We also tested financial literacy in the treatment group, using the same questions as the S&P Global Financial Literacy Survey. We found that those who pass a financial literacy test report lower inflation expectations.

Figure 2: Proportion of respondents predicting inflation >6% next year, based on whether they passed or failed a financial literacy test

These results show that question design matters a great deal. They do not, however, give the final word on the best way to design inflation surveys. Central banks should continue to experiment to ensure the best possible data collection.