As of Monday, the first of 67 ‘Tier 3’ local authorities have started community COVID-19 testing in the UK. This mass testing effort is intended to help them stop the spread of coronavirus and slow the rapid transmission of the virus to lower Tiers. As local leaders of Oldham, Lancashire and Kirklees launch their testing programs, we highlight some of the key lessons from Slovakia’s mass-testing for our local leaders to consider.

Last week, a UK study showed that the world’s first whole country testing program in Slovakia reduced case prevalence by a whooping 60% in a single week. This goes to show that mass testing – if done well – can be a powerful weapon in the fight against COVID-19.

Mass testing reduces COVID-19 prevalence

If China’s experience with mass testing of large cities (Wuhan, Qingdao, and Kashgar) wasn’t enough proof that mass testing works, we now have evidence from the first European country that tested its whole population over the space of two weekends. A study co-authored by Wellcome researchers and Slovak Department of Health experts – including the Secretary of State – shows that a round of mass testing decreased case prevalence a week later by 60% on average. Researchers found this effect when they compared:

- the prevalence found in the four counties tested in a pilot and then retested a week later in a national round and

- the prevalence in 45 counties tested first in the national round and then retested a week later in a follow-up regional round.

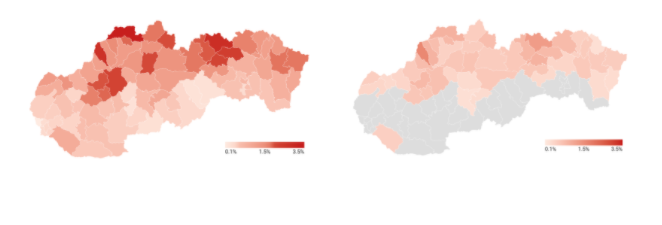

Figure 1. Prevalence in Slovakia’s counties more than halved a week after mass testing (from an average of 1.1% to 0.6% a week later)

Whilst some have argued that this big reduction is partly due to the parallel lockdown, we think this argument doesn’t hold for a number of reasons.

Firstly, there was only a partial lockdown in place – in that guidance permitted all people who tested negative (90%+) to immediately enjoy the equivalent of Tier 1 freedoms (e.g. going to work, non-essential shopping, restaurants open for outdoor and takeaway, Rule of 6). This means that we cannot attribute the reduction in prevalence to a lockdown that was not fully there.

Second, the reductions in coronavirus prevalence achieved after mass testing came about far more rapidly than any lockdown has achieved to date. Mass testing reduced the prevalence of COVID-19 by around 60% after a single week – whereas lockdowns have only achieved half of the reduction over the course of several weeks. Authors simulations also show that mass testing did the heavy lifting, with lockdown alone unable to move the dial so quickly – but the combination of the two did help.

Finally, a good indication of the relative effect of a lockdown vs mass testing is what happened to other European countries under lockdown but with no mass testing, in a nice natural experiment.

Taken together this offers countries a far more effective and cost-effective way of reducing coronavirus transmissions than entering into economically costly lockdowns.

Lessons for local authorities

1. Make it easy

To enable large numbers of people to get tested, ease and accessibility are key. This means first providing a large number of sites for testing. Slovakia created roughly 1,000 sites manned by 8,000 staff per 1,000,000. For a city like Medway or Liverpool this would mean 280 and 500, respectively.

Other ways to increase accessibility include ensuring testing sites are conveniently located, for instance within 15 minutes travel distance and not tucked away in a remote difficult to find place. There should be enough available slots and long opening hours to accommodate as many people as possible. Registration and booking online, if required, should be as frictionless as possible.

2. Incentivise

Much of Slovakia’s success is likely due to the presence of a strong ‘carrot and stick’ incentive approach. ‘The carrot’ was that people who tested negative were able to exit lockdown and go to work, visit non-essential shops, eat outdoors at restaurants, meet with up to 6 people and travel around the country. ‘The stick’ was that people without a test were unable to work – even from home – and had to self-isolate without a right to sick leave, unlike those who tested positive.

Whilst this model is unlikely to be replicated in the UK, other incentives could be put in place, such as:

- Enabling access to certain institutions (schools, university, social care)

- Providing tickets for local sporting or cultural events

- Administering discounts for local stores and hospitality

- Providing special rewards for groups of 5 and more who get tested at a time (e.g. extra discounts)

- Giving people time-limited access to socially-distanced venues post-test

- Or, truly radical, reopening hospitality & other venues provided a large share of the population got tested (75%+) and the prevalence fell.

3. Be safe

Mass testing using lateral flow tests is not without its risks – so precautions are essential to ensure that the risks do not outweigh the benefits.

In Slovakia, a curfew (i.e. stricter lockdown where people can only leave the house between 5 am to 1 am) was imposed a week prior to the testing. This was to ensure minimum social mixing immediately prior to the test, to reduce the chance of people being in the incubation period. Tests were administered by healthcare professionals, as studies show that laymen are much less likely to do them well than lab scientists or healthcare staff. In addition to these safety precautions whole households were required to self-isolate if one of their household members received a positive test result , even if they did not test positive themselves and certificates and fines were used to check and enforce self-isolation.

We believe that mass testing by local authorities in the UK can have as much impact on coronavirus prevalence in the UK, as did the Slovakian government on prevalence there, by doing the following:

- Use trained staff or assisted test administration at test sites , especially with at-risk groups;

- Provide clear advice to test administers on how to do the test well (i.e. how far in the nose to go) with guidance on common mistakes;

- Focus on attracting disengaged communities with high prevalence rates to get tested;

- Caution people with negative tests to continue complying with general guidelines and recommend repeat and frequent testing where possible;

- If providing incentives, find ways to link them to people’s ID to avoid fraud;

- Provide timely advice and links to additional support on self-isolation for those who test positive. And firmly let people know that their household needs to self-isolate, given they’re all close contacts.