Introduction

One of the most significant technical innovations in policing in recent years has been the emergence of the body worn video camera (BWVC), a form of closed circuit video. Though police forces across the world have begun to use the new technology to increase efficiency and improve policing outcomes, there have been relatively few robust studies as to their effects.

Relatively small studies in the US found initial evidence that BWVCs reduced use of force and fewer complaints against officers. Two small-scale trials in the UK found evidence of BWVCs leading to an increase in the proportion of detections that resulted in a criminal charge. A larger trial at the London Metropolitan Police found a reduction in complaints too but found no significant changes on metrics related to Stop and Searches and number of arrests for violent crimes. A recent meta-analysis of ten multi-site randomised controlled trials and found on average a 15% increase in assaults against officers wearing BWCVs and on average no impact of wearing BWCVS on use of force. However, use of force rates were 37% lower compared to control conditions when complying with the protocol to keep BWVCs switched on throughout all public interactions. When officers used their discretion to switch cameras on and off, use of force was 71% higher.

The Behavioural Insights Team conducted a largescale RCT with Avon and Somerset Constabulary to test the impact of BWVCs not only on crime and justice outcomes, but also on the police officers themselves.

The impact of police officers using BWVCs is fundamentally behavioural. By giving officers access to this technology, we expect behavioural changes from both the police and those with whom they come into contact. If both parties know they are being monitored, we anticipate impacts on: both parties’ compliance with the law and related procedures; both parties’ confidence in their recollection of the details of the interaction. Additionally, richer quality evidence may lead to efficiency gains at prosecution.

Trial design

The RCT was set up as follows: 1,100 eligible police officers from across the Constabulary were involved in the trial. Over the duration of the trial, 407 officers* were randomly assigned to receiving a camera, and asked to use it according to protocol; the remaining 693 officers comprised the comparison or control group. As part of ASC’s protocol at that time, officers were instructed to only use the cameras for Stop and Searches and domestic abuse incidents. It was not possible to track whether cameras were switched on at the time of an incident. This is in line with the business as usual process: footage is not reviewed unless it is serving as evidence during a prosecution or complaint.

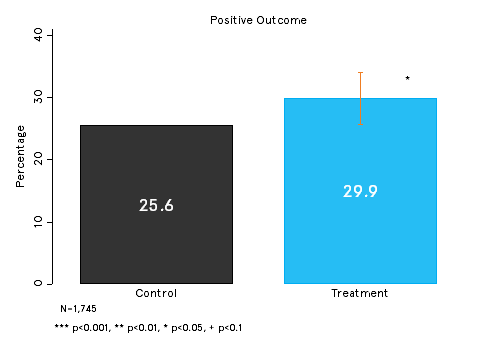

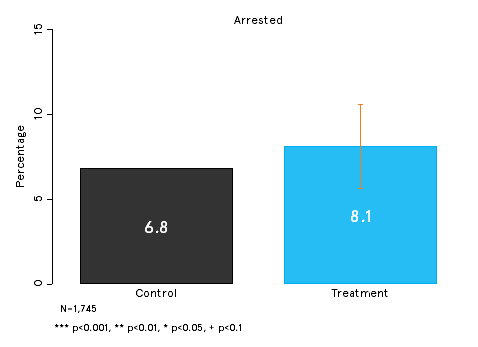

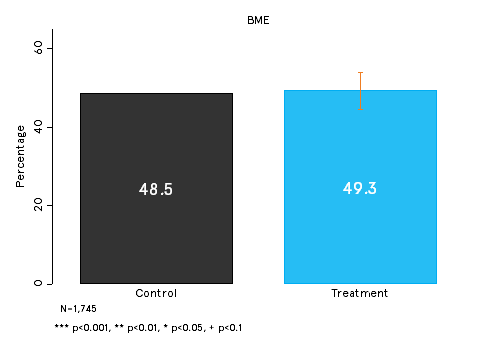

The trial results showed that being assigned a camera led to an increase in the types of Stop and Searches that led to further action** (Figure 1) but had no impact on arrests or the ethnicity of the suspect being stopped and searched (Figures 2 and 3). This could mean that the presence of a BWVC somewhat increased officers’ accountability for conducting necessary Stop and Searches and is very much in line with the protocol that suggested BWVC had to be turned on for Stop and Searches.

Figure 1. BWVC increase the likelihood of a Stop and Search resulting in a positive outcome

Figure 2. No significant impact of BWVC on the likelihood of a suspect being arrested

Figure 3. No significant impact of BWVC on ethnicity of those being stopped and searched

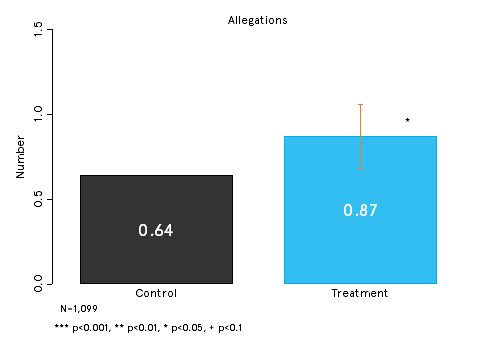

Each complaint the police force receives is made up of one or more allegations***. We find a significant increase in the number of allegations made against officers but no impact on the number of complaints (Figure 4). This suggests that complaints are becoming more detailed (being composed of more allegations) when officers have BWVCs.

Figure 4. BWVCs are associated with a significant increase in the number of allegations made against officers

Our final set of quantitative findings related to officer wellbeing: one of the key predictors of burnout in employees is often sick leave and absenteeism. We found a reduction in the number of sick days for officers who were allocated a camera (by 3.3 days) whilst the number of absence spells remained unchanged. This indicates that BWVCs may be reducing the amount of physical or mental impact on an officer, leading to quicker return-to-work rates following a spell of absence. The impact of BWVCs on officer sickness absenteeism levels has, to the best of our knowledge, not been evaluated in other BWVC trials and our results show promising early evidence.

We also collected qualitative survey data before and after the launch of the new cameras: providing us with more detailed and nuanced information on officers’ perceptions and experiences. Overall these were very positive, with only a few areas of improvement in terms of offering high quality training and ongoing support to officers using BWVCs. ASC has addressed these issues in its continued usage of BWVCs. The qualitative data supports our hypotheses on the impact of the cameras on absenteeism: the majority of respondents agreed they felt safer and less vulnerable with a BWVC.

Conclusion

The results of this trial indicate that BWVCs can improve police decision making in several ways: leading to fewer unnecessary Stop and Searches and improvements in metrics related to prosecutions. Additionally, we find wellbeing-related benefits to wearing a BWVCs, such as reduced sickness absenteeism rates and self-reported feelings of safety when conducting a Stop and Search. The findings also flag the need for further research on the impact of BWVCs: for example, the increase in allegations against officers could be explored further by analysing metrics that could not be collected as part of this trial (such as the reason for the complaint and levels of use of force by the officer).

Now that BWVCs are becoming increasingly prevalent and even a standard tool at disposal of frontline police officers, it is even more important that the impact of the cameras is evaluated robustly. We hope that the findings of this large scale randomised trial be considered in conjunction with the evidence from earlier studies so that BWVCs can be deployed in the most effective way: protecting both citizens and officers and helping to establish a fair criminal justice system. In addition to continuing to assess how BWVCs impact officer behaviour and criminal justice outcomes (including bribery in other countries), future research should investigate how cameras are introduced further (forces differ widely in their usage protocols and there are various camera models/features available). Exploring how to most effectively use BWVC footage will be another behavioural challenge: footage can for example be used for training purposes.

* Not all officers who were randomly allocated a camera were on active duty at the start of the trial or during the trial. In that case, the camera was randomly reassigned to another participant, giving a total of 407 officers who were assigned a camera.

** Examples of these types of Stop and Searches are those that detect possession of cannabis (resulting in a warning), or possession of stolen articles (leading to an arrest or a voluntary interview).

*** When a person makes a complaint stating an officer has pushed them and was rude, this will be logged as one complaint with two allegations.