A third of the UK population spent at least one year in relative income poverty between 2011 and 2014.

Traditionally policymakers and anti-poverty organisations such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) have focused on boosting people’s economic capital (e.g., income) and human capital (e.g., educational attainment) to reduce poverty. While investments in these areas have led to important gains in opportunity for many Britons, emerging research from behavioural science shows that other less tangible resources, which derive from psychological, social and cultural processes, significantly influence people’s ability to overcome disadvantage.

BIT was commissioned by JRF to examine the role of individual decisions in shaping people’s experiences of poverty in the UK and to identify the drivers of these decisions. This reflects JRF’s interest in looking beyond traditional, structural drivers of poverty. Our findings, based on a review of the published literature, are presented in a new report, launched today.

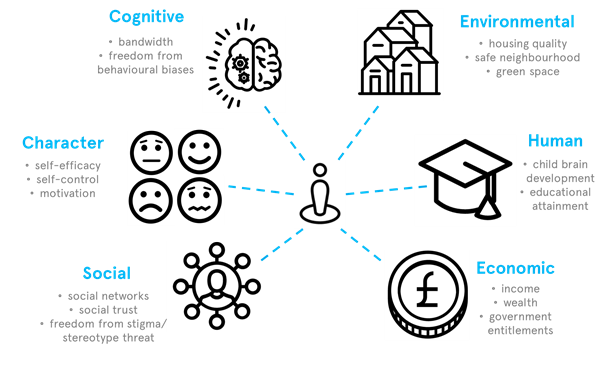

Building on the concepts of economic and human capital, our report proposes a more expansive capital-based model of poverty and decision-making, encompassing environmental, social, character and cognitive capital (Figure 1). For example, an individual may use their social capital (e.g., trusted social connections) to identify labour market opportunities; but being low in environmental capital (e.g., overcrowded housing) may reduce opportunities for parents to talk with their child in ways that build their human capital (e.g., speech development).

Figure 1. Types of capital resources (including examples)

We applied our capital model to six key decision areas that influence poverty in the UK:

- choosing low-cost credit;

- accumulating savings;

- moving into work from unemployment;

- accessing government entitlements;

- responsive parenting; and

- applying to post-secondary education.

Under each of these six headings, we explain both how a lack of the different types of capital influence individual decisions, and we showcase potential interventions to overcome the negative effects.

The good news is that, while interventions to boost economic and human capital often take a long time to produce results, investing in a person’s psychological resources can often have very fast and wide-ranging benefits. For example, one study we reviewed found that people in poverty performed better on tests (equivalent to a 10 point increase in IQ), and were more likely to consider making use of programmes that would benefit them, if they had recently been asked to recall a proud moment or past achievement (Hall, Zhao, & Shafir, 2014). By comparison, another study we reviewed found that when low-income students were asked to answer demographic questions about their parents’ income and occupations before a test, they performed worse than the low-income students who were not asked these questions (Spencer & Castano, 2007). This psychological perspective of inequality in the UK highlights that processes which build in small empowering interactions between users and service providers, at key moments, can potentially boost a person’s psychological resources which can, in turn, increase their ability to overcome disadvantage.

To give you a flavour of the report, below we explain some of the ways that cognitive, character and social capital influence social mobility, via decision-making.

Cognitive capital: Timely prompts and the take-up of entitlements

Despite the obvious financial benefits, many people on low incomes do not take up the welfare payments they are entitled to. Research shows that money worries can absorb cognitive bandwidth, leaving less cognitive resources to make optimal decisions (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2014). A UK study which examined the impact of GPs offering advice to older people about their welfare entitlements found no real improvement in health outcomes but 58 per cent of participants gained a welfare benefit (Mackintosh et al., 2006). Some benefits were non-financial, such as a disability parking permit, but the median financial award was £58 per household per week. This highlights that there may be many timely opportunities for trusted service providers to encourage people to take-up entitlements that could benefit them, for example at the Post Office.

Character capital: Self-efficacy and responsive parenting

A parent’s belief in their own capabilities can have a significant effect on how they parent, and has been shown to affect their child’s educational attainment. Parenting self-efficacy is bolstered by parental education and social support (Seefeldt, Denton, Galper, & Younoszai, 1999; Young, 2011). Conversely, stressors linked with living in poverty, such as financial strain, have been shown to undermine a parent’s self-efficacy, diminishing their belief in their abilities and perceived control (Carroll, 2013; Machida, Taylor, & Kim, 2002).

A number of parenting interventions involving home visits by health workers have had positive effects in preventing intergenerational poverty. The most successful interventions help parents build on existing parenting practices, rather than introduce lots of new information, which increases parental self-efficacy and reinforces positive habits. A trial in Jamaica found that 20 years after home visits to new parents, adults who had been in the treatment group as children were earning 25 per cent more than those who had been in the control group (Gertler et al., 2014).

Social capital: Social networks and applying to post-secondary education

Qualitative research from the UK shows that when young people from less well-off backgrounds make career decisions, they value and rely on informal information (from their social networks) more than formal information (such as careers services) (Greenbank & Hepworth, 2008).

Similarly, a quantitative US study found that high school graduates were more likely to enrol in college if their friends planned to attend college and if their parents were involved in the school they attended (e.g., contacting the school to volunteer time in the classroom or discuss academic matters). Regardless of a student’s own friends and parents, there was an additional positive effect on college enrolment from social capital at the school level: college enrolment was related to the average number of students that reported that most or all of their friends planned to attend college, and average parent-initiated contact with the school about academic matters (Perna & Titus, 2005).

These findings highlight that policymakers should look for ways to use the powerful role of social networks to support young people in their decision to stay in education.

Key take-away

The report presents 18 specific policy recommendations. Below we provide just one key take-way:

Cognitive load test: We argue that policymakers should not reduce the value of their investments in anti-poverty programmes through complex and stigmatising application processes and eligibility checks which absorb cognitive bandwidth. We all have limited mental processing capacity to reason, to focus, to learn new ideas, and to resist temptation. The worries involved in making ends meet every day already deplete bandwidth so government services aiming to tackle disadvantage – such as savings schemes, employment advice and parenting programmes – should be required to pass a cognitive load test to ensure these services do not make it harder for people on low incomes to make good decisions for themselves.

Conclusion

Investing in traditional forms of capital – economic and human – remains important for reducing poverty in the UK but understanding how less tangible forms of capital influence decision-making is useful in two respects: first, it can help to explain why some well-intentioned interventions may fail; and second, it can open up a new set of tools to address poverty.

You can read a summary of the findings from this report here.