As we wind down for the festive season, we’ll soon be seeing lots of adverts for post-Christmas sales. As tempting as they may be, the message from COP26 just a few weeks ago is that we are at a critical point in time for determining the future wellbeing of the planet.

We know that our material consumption and waste far exceeds the planet’s current capacity, and that 62% of future emissions reductions require changes in human behaviour. This includes how we buy and use products.

Producing new products can create a large carbon footprint. For example, did you know that on average manufacturing a brand new sofa generates 90kg of carbon dioxide equivalent, which is roughly equivalent to driving a car for 220 miles? At the same time, 100,000 tonnes of appliances are sent to waste facilities and landfill over the winter period alone.

Buying second-hand rather than new where possible can be win-win. It can help prevent waste and reduce carbon emissions, and also provides the opportunity to grab a bargain, find something unique, or even get creative and upcycle an item.

Online re-commerce platforms are helping to drive this change by connecting communities and enabling consumer-to-consumer transactions. But barriers also exist: buying pre-owned doesn’t always give us the same choice, convenience, quality, or consumer protections. There are real frictions to resolve there, but also perceived ones, where attitudes may be targeted with some well-crafted messages.

BIT worked with Gumtree, one of the UK’s largest websites for local classified advertisements to investigate what can be done to further encourage people to use re-commerce platforms and buy second-hand.

Testing approaches to increase purchasing of second-hand items

We ran an online experiment with 3,003 UK adults to test whether environmental or value-focused messages could encourage customers to buy second-hand items. Participants were presented with 3 pairs of ads (a desk, TV and sofa), featuring a second-hand item and a comparable new item and asked which one they would prefer to purchase in the real world. Participants were randomly assigned to one of 5 arms:

- Control – No extra messages or labels.

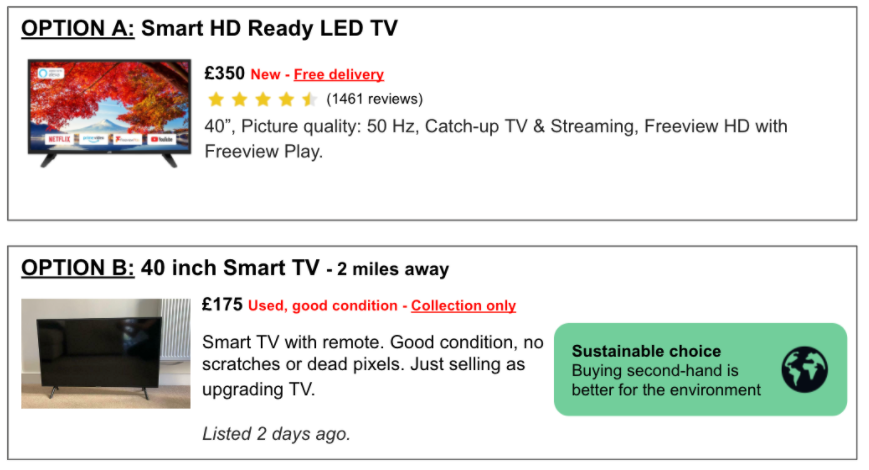

- Cost frame – A big ad emphasising savings that can be made when buying second-hand (on screen 1) plus a ‘smart choice’ label on the second-hand item listing (on screen 2).

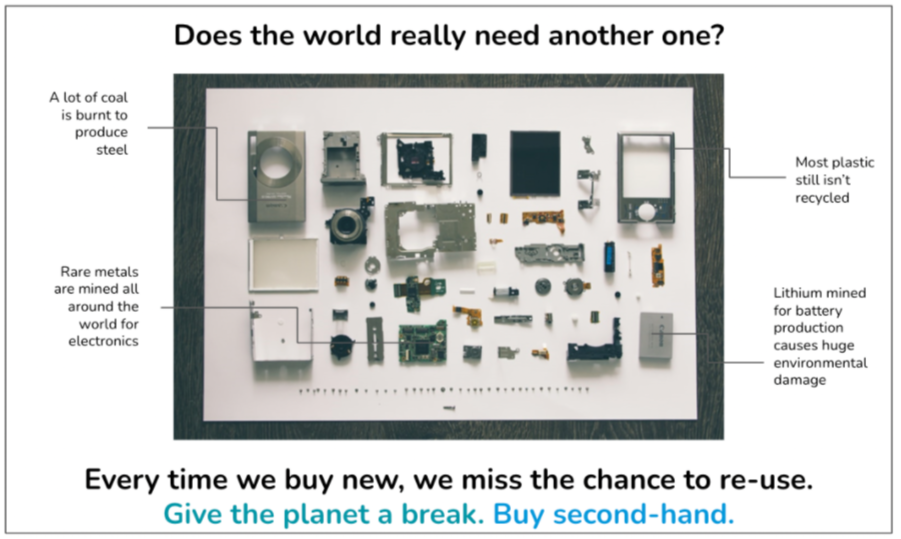

- Environmental frame I (Impact) – A big ad highlighting the energy and materials that go into producing a new item, asking ‘does the world really need another one?’ (screen 1), plus a ‘sustainable choice’ label on the second-hand item listing (on screen 2).

- Environmental frame II (Waste) – A big ad conveying the amount of items thrown away every year and that buying second-hand can help to avoid waste (screen 1), plus a ‘thrifty choice’ label on the second-hand item listing (on screen 2).

- Environmental frame III (Humour) – A big ad mimicking a pet-adoption ad, asking people to consider adopting one of the many items which are abandoned by their owners every year (screen 1), plus a ‘green choice’ label on the second-hand item listing (on screen 2).

Figure 1. Example of Environmental frame I (Impact) – screen 1

Figure 2. Example of Environmental frame I (Impact) – screen 2

After the experiment, participants answered survey questions about their experiences with buying second-hand products and their attitudes towards re-commerce platforms. Below are our key recommendations for encouraging customers to buy second-hand instead of new.

Draw attention to the environmental and financial benefits of buying second-hand

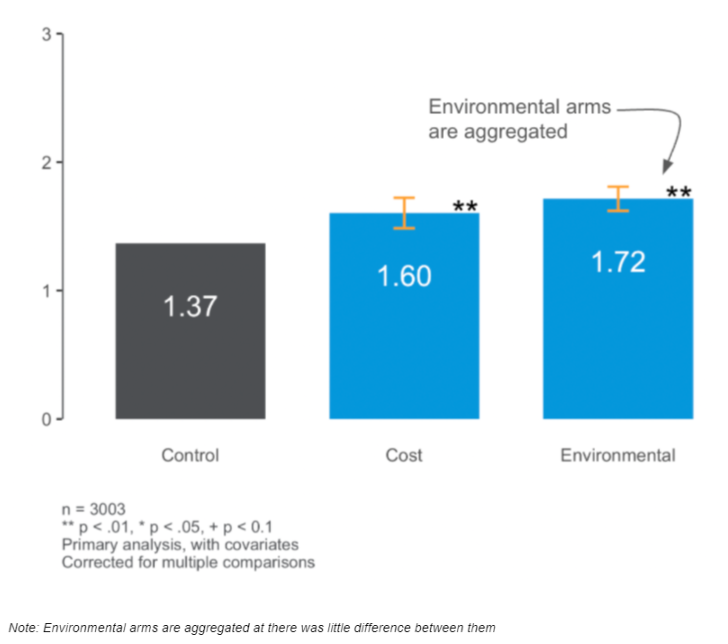

Our primary finding was that in comparison to the control, all four messages tested increased selection of second-hand items in the experiment (with little difference between the three environmental messages).

Figure 3. Number of used items selected (out of 3)

We also found that there was a gap between people’s intentions as indicated by their level of climate worry and their behaviour in the experiment. 7 out of 10 people were highly worried about climate change but only 2 out of 10 went for all second-hand items in the control arm. Our interventions reduced this intention-action gap as 3 out of 10 in the environmental arms went for all second-hand items.

This suggests that simply making the environmental and financial benefits of buying second-hand more salient can encourage purchasing of second-hand items.

Use appealing language

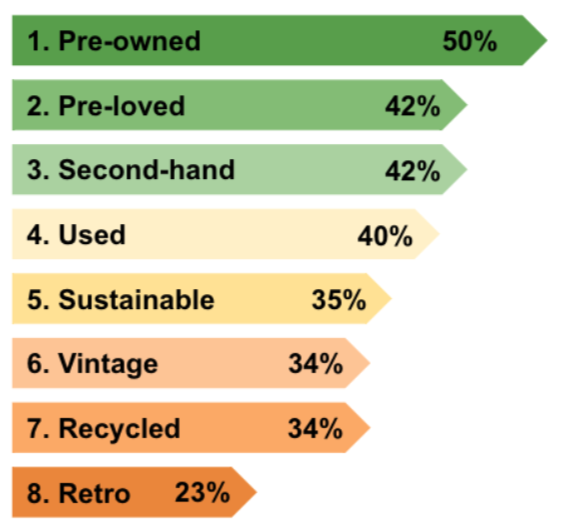

In the survey, participants were asked to rank their preferred term for describing second-hand items.

Figure 4. Ranking of preferred phrase for “second-hand” (% selecting phrase in their top 3 choices)

The results suggest organisations should consider using appealing language to encourage sustainable behaviour. This echoes findings from previous work, such as our trial on encouraging sustainable food consumption, where framing a meat-free meal as ‘field-grown’ nearly doubled the number choosing it. In this case, pre-owned and pre-loved were the most popular choices and should be considered when describing second-hand items and marketing re-commerce platforms.

Go beyond messaging to solve real barriers

The reasons participants gave for selecting new items over second-hand in the experiment varied across products. Product life is a particular concern for electronic items, whereas furniture is inconvenient to collect.

In the survey, participants also reported prevalent barriers to buying used goods across the board, most notably lack of warranties and not being able to return items.

This means that going beyond messaging to develop tangible solutions to address prevalent barriers is important for further encouraging people to buy second-hand. Some solutions may be applicable to all products (e.g. making it easier for people to find what they are looking for), whereas others may need to be tailored to address specific product barriers (e.g. offering delivery for furniture/large items).

Next steps

Our results are very encouraging, but we were unable to fully recreate the buying experience in a laboratory. We recommend that messages are validated “in the field”, measuring real purchase behaviours.