One in ten hospital outpatient appointments is missed – people don’t turn up, and don’t cancel or rearrange in advance. That’s 5.5 million appointments every year in England alone. Missed appointments lead to people not getting the care they need, when they need it. They also lead to costs to the NHS, some of which arise because hospitals end up introducing complex overbooking procedures.

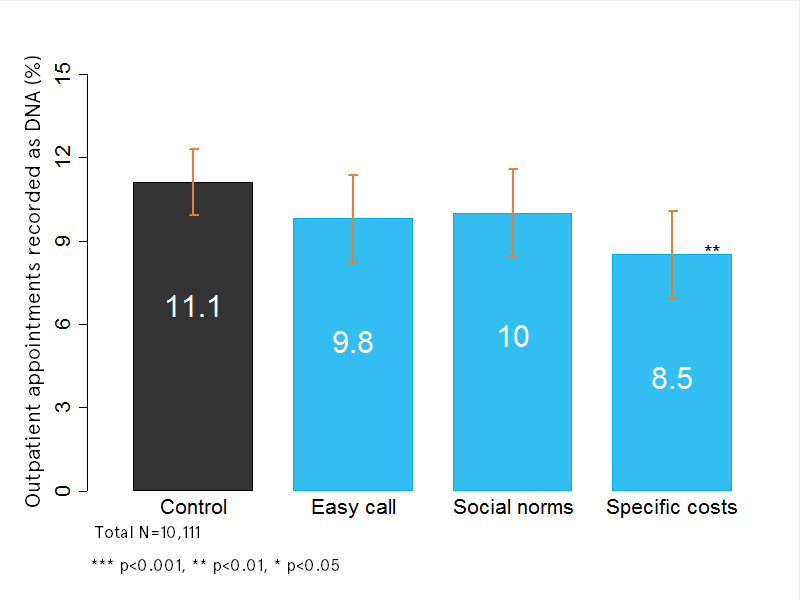

The Behavioural Insights Team worked with the Department of Health and Imperial College London to find a cheap and easy way to reduce these no-shows. The project led to a 25% reduction in missed appointments (from 11.1% to 8.5%) for no extra cost, a result that was published in the academic journal PLoS One a couple of weeks ago. So how did we do this?

Many hospitals use SMS messages to send people reminders that their appointment is coming up soon. We know these reminders are effective. But we don’t know whether any specific wording or concepts work best at encouraging people to turn up (or rearrange). This matters because, for example, the NHS is currently spending money on marketing campaigns without knowing if the messages are effective or not at reducing no-shows.

So all we did was run a randomised trial to see if changing the messages in the SMS appointment reminder led to more people turning up or not. Patients attending five different clinics at Barts NHS Trust were randomly allocated to receive one of seven different messages. We tried out a variety of concepts from the behavioural sciences, including fairness to others, social norms, and reducing friction costs. We didn’t know what would be most effective.

Percentage of outpatient appointments recorded as “did not attend”

The clear winner was a message that pointed out the approximate cost of the missed appointment to the NHS (£160). We got the same result when we ran the trial again, which makes us confident it’s a real result. Interestingly, putting the same idea in more general terms, without a specific cost, was less effective – again showing how details matter.

We think this message should be used more widely by NHS Trusts who want to reduce their missed appointments. There is a case for thinking more broadly about how cost information could be used to reduce waste in the NHS (as show in this study, for example). However, this should only be done in carefully-selected areas, and with robust evaluation to make sure there aren’t any unintended consequences. As always, testing, learning and adapting is the best way forward.