Last week Professor Richard Thaler and Professor Cass Sunstein published Nudge: The Final Edition. As many of our readers will know, BIT was built on the ideas developed and popularised in the original edition, and we have been hugely grateful for the inspiration, energy and guidance Richard and Cass have provided over the past decade — to us and the wider behavioural science community. The publication of Nudge fundamentally changed my thinking and career, and spawned a whole set of institutions and programmes around the world.

The updated edition is packed with brilliant examples of how nudges have evolved in their reach and sophistication — from moving towards data-driven smart disclosures, through measuring and tackling ‘sludge’, to the massive impact of green energy defaults. Richard and Cass have not just updated their seminal book with a decade of cutting-edge research and thoughtful reflection, but also wrestled with and responded to challenges and critiques.

The updated edition is packed with brilliant examples of how nudges have evolved in their reach and sophistication — from moving towards data-driven smart disclosures, through measuring and tackling ‘sludge’, to the massive impact of green energy defaults. Richard and Cass have not just updated their seminal book with a decade of cutting-edge research and thoughtful reflection, but also wrestled with and responded to challenges and critiques.

Indeed, Nudge’s phenomenal success has not come without its fair share of critics. These are captured in a new chapter at the end of the book referred to as “The Complaints Department.” Richard and Cass respond to a number of key critiques, many of which have faded over time. But with typical humility, they also acknowledge that these criticisms have sharpened their thinking over the past decade, and underlined their belief that nudges are not a silver bullet, but should be an important part of any organisational tool box. This new edition and final chapter of Nudge encouraged me to reflect on when and how we at BIT can use nudges and other behavioural tools to maximise impact over the next decade.

The “what ifs”: Theoretical challenges to nudging

Richard and Cass highlight that many of the noisiest critiques have been hypothetical rather than grounded in the reality of the way nudges have been deployed in practice. We have witnessed this first hand: since Richard helped establish our team back in 2010, and partly because the term nudge is a headline writer’s dream, we quickly became known as ‘The Nudge Unit’. When we first established in the heart of the UK government, there were vociferous concerns around the potential for widespread mind control, manipulation and skullduggery. These concerns continued as we expanded our work overseas, and as other BI Units have been set up around the world. Indeed, when I moved to Australia in 2012 to help the New South Wales Government set up their own team, it made front page news, while another article started with the opening line ‘A REALLY bad idea is being imported to Australia’. I tried not to take this personally.

These more sensationalist critiques have generally faded over time as teams across the world have published important and impactful results. It is much easier to argue against a theoretical straw man and dystopian futures than with the reality of better designed savings defaults, or easier access to government services and benefits.

While Richard and Cass efficiently counter a number of largely unfounded concerns — for example, around ‘slippery slopes’ and ‘sneakiness’ — there remains a number of legitimate critiques of nudging and of the BI community. The two that I wrestle with most often in practice, and which I believe require further discussion, are:

- When we should use nudges or ‘boosts’, and;

- The merits of nudges versus mandates and bans.

Richard and Cass’ response is typically pragmatic, rightly underlining that in both cases it is not an either/or; you can and should use nudges alongside educational and regulatory approaches. While I agree with this position, I think it is worth reflecting on whether, in practice, the BI community has got this balance right. In the pursuit of demonstrable results and so called ‘quick wins’, have we sometimes focused too much on low cost, light touch nudges — such as the rewriting of letters that helped popularise the approach in the early years? And has this focus on a relatively narrow set of nudges come at the expense of interventions that require people to really pause, reflect and learn, and for governments to make legislative changes or tackle more systemic reforms?

In the pursuit of demonstrable results and so called ‘quick wins’, have we sometimes focused too much on low cost, light touch nudges — such as the rewriting of letters that helped popularise the approach in the early years?

1. When to nudge or boost?

One critique of nudging is that governments and organisations should primarily seek to educate or ‘boost’ people’s capabilities, rather than design choice architecture around our behavioural biases. Essentially, the argument here is that nudges are implicitly a form of dumbing down, which are used because we don’t trust people to make the right choices or learn from their mistakes.

Richard and Cass note that while their careers in academia hint at their pro-education disposition, we should acknowledge that people have limited cognitive bandwidth and often rely on System 1 automatic behaviours. And so we should design systems that recognise this — especially in high risk areas with little opportunity for regular feedback. For example, they highlight that financial literacy educational programs are generally not very effective or sustainable, so it’s better to design smart defaults into savings programs, rather than try to teach people about compound interest rates.

This is certainly true in my view; there are dozens of examples of educational programs across finance, health and environmental issues that are well-meaning, but that have proved to have almost no impact in practice. I also worry that I, and others in the BI community, may have swung too hard in the other direction – taking Richard’s mantra of ‘make it easy’ too far by focusing primarily on designing interventions around these automatic behaviours, and not thinking critically enough about when we could provide ‘just in time’ education and personalised feedback at key moments. Professor Peter John and his colleagues have recently made a convincing argument for ‘nudge plus’ interventions, which contain this type of reflective strategy embedded into the design of a nudge.

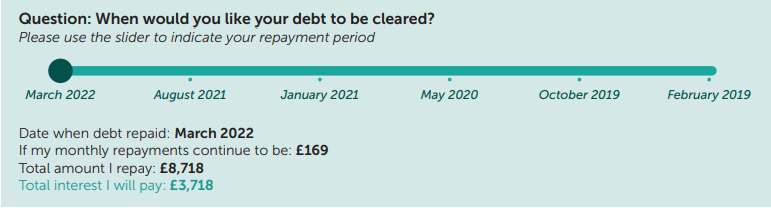

There are a number of illustrative examples of this that we can point to. Sticking with household finances, a trial we ran to introduce online ‘sliders’ to illustrate to consumers the length of time it would take to pay off credit card debt at different repayment rates is a good example of this in practice. In effect, this intervention highlights the commercial nudges being used to influence their behaviour and attempts to counter that at the key moment of starting repayments. And our use of commitment devices in a range of areas, from employment to domestic violence, has similarly sought to create moments of reflection and planning to create sustained behaviour change.

To give another, more involved example, in Australia we have designed an 8-week program (Digital Compass) that seeks to help teenagers make better choices online. It does this by drawing back the curtain on how social media companies have designed features — such as streaks, likes, filters and algorithms — which keep them on their phones and influence their behaviour and wellbeing in a number of ways. Young people then use this understanding to design and agree codes of behaviour among their peers and make practical changes to their tech and apps (for example, turning off notifications, using greyscale, and reviewing who they follow on social media). In essence, we are supporting young people to redesign their online and offline environments, through a series of self and peer network nudges.

Yet I believe that these types of interventions are a relatively small subset of the BI community’s overall portfolio, and navigating the balance of when and how to design for more automatic behaviours, and when to prompt more reflective engagement is something that I feel deserves more attention over the next decade.

2. To nudge or to mandate? Choosing the right tool for the job

The second, louder, and more common critique is that nudges are less effective at changing behaviour than mandates, and act as a trivial distraction from more traditional and powerful policy levers. Richard and Cass argue that there is room for both, and compare nudges to a swiss army knife — versatile, cost effective and with a snazzy array of tools to draw on as needed. But they underline that to tackle complex issues like climate change, we need harder regulatory measures — we need ‘jackhammers and bulldozers’, not swiss army knives.

I like this metaphor, and certainly agree that we need to deploy a range of power tools to make a dent in society’s most pressing problems. But rather than focusing on nudges and mandates as a dichotomy, I see the role of BI practitioners as using our understanding of human behaviour to help governments and organisations select the most suitable tool for the problem at hand, and to sharpen and more precisely guide their application. While the power of jackhammers and bulldozers are sometimes necessary, they are by nature aggressive and blunt. Much better to use behavioural science to help deploy them in a more targeted and surgical way.

I see the role of BI practitioners as using our understanding of human behaviour to help governments and organisations select the most suitable tool for the problem at hand, and to sharpen and more precisely guide their application.

For example, we have shaped smarter consumer regulations, reformed major delivery systems, and designed taxes — such as the UK’s added sugar levy — by drawing on a more sophisticated and behavioural account of consumer and market dynamics than traditional economic models. This is partly why we called ourselves ‘The Behavioural Insights Team’, alongside the more colloquially used ‘The Nudge Unit’ — because nudges have always been just one important part of our armoury.

But in truth, these types of major regulatory reforms have also typically only made up a minority of the collective work of BI units around the world. While lots of energy is devoted towards ‘advisory work’, this is often tilted more towards the take-up and communication of policies, rather than more fundamentally to their design. It’s important for the BI community to reflect on why many have become skewed towards a subset of low cost and light touch nudges. The swiss army knife’s main blade has undoubtedly proved both cost effective and impactful over the past decade, and there remains huge potential in using it to cut through the administrative ‘sludge’ that continues to clog up systems. But it’s important these demonstrable results don’t become narrowly self-reinforcing, so that we are only brought in to solve particular parts or types of problems. We need to critically assess how we can more regularly deploy a wider range of tools, in more creative and precise ways, in order to really make a dent in our most pressing societal challenges. Otherwise there is a danger, like the swiss army knife, we become a neat party piece that becomes less relevant over time.

This need to apply a more diverse set of behavioural tools and methods has been laid bare by COVID-19. Over the past year and a half, BI Units around the world have been working hard to support governments and organisations to diagnose new behavioural problems, and to rapidly design, implement and test new policies and services. Much of this critical work will likely never be published, and will likely prove harder to point to clear causal impact, but it provides the BI community the opportunity to build on new, more iterative and holistic ways of working.

This type of behaviour change is hard work, higher risk, less linear, and requires a more diverse set of skills, funding and behavioural tools. But it is the type of work I believe we can and should do more of. In order to chart the path forward, BIT will soon be releasing its manifesto for the future of behavioural science, which sets out these and other issues, and charts a route for addressing them. Hopefully this will help us to rise to Richard and Cass’ provocation for us to tackle and make a dent in society’s most pressing problems.

Rory Gallagher was one of the founding members of The Behavioural Insights Team, the original ‘Nudge Unit’. He is currently the Managing Director for BIT’s Asia Pacific offices.