This is the fourth blog in our Behavioural Government series, which explores how behavioural insights can be used to improve how government itself works.

You might say – whatever the public cares about.

The fact that people care about an issue is of course important in a democracy – no politician will last long if they ignore public opinion. However, this can mean important matters which don’t get much public attention may be neglected, leading to big problems later.

One cause of this selective public attention is availability bias: the tendency to think an issue is important because it comes to mind easily. An example is a person thinking that plane journeys, but not car trips, are dangerous because they have seen airplane crashes in the news. In contrast, car crashes are routine enough that they do not attract much media coverage, and so examples of them do not come to mind as quickly.

One example of the impact of availability bias is the number of additional Americans who died in road accidents by switching from flying to driving after 11 September 2001, which exceeded the number who died in the attacks after just three months.

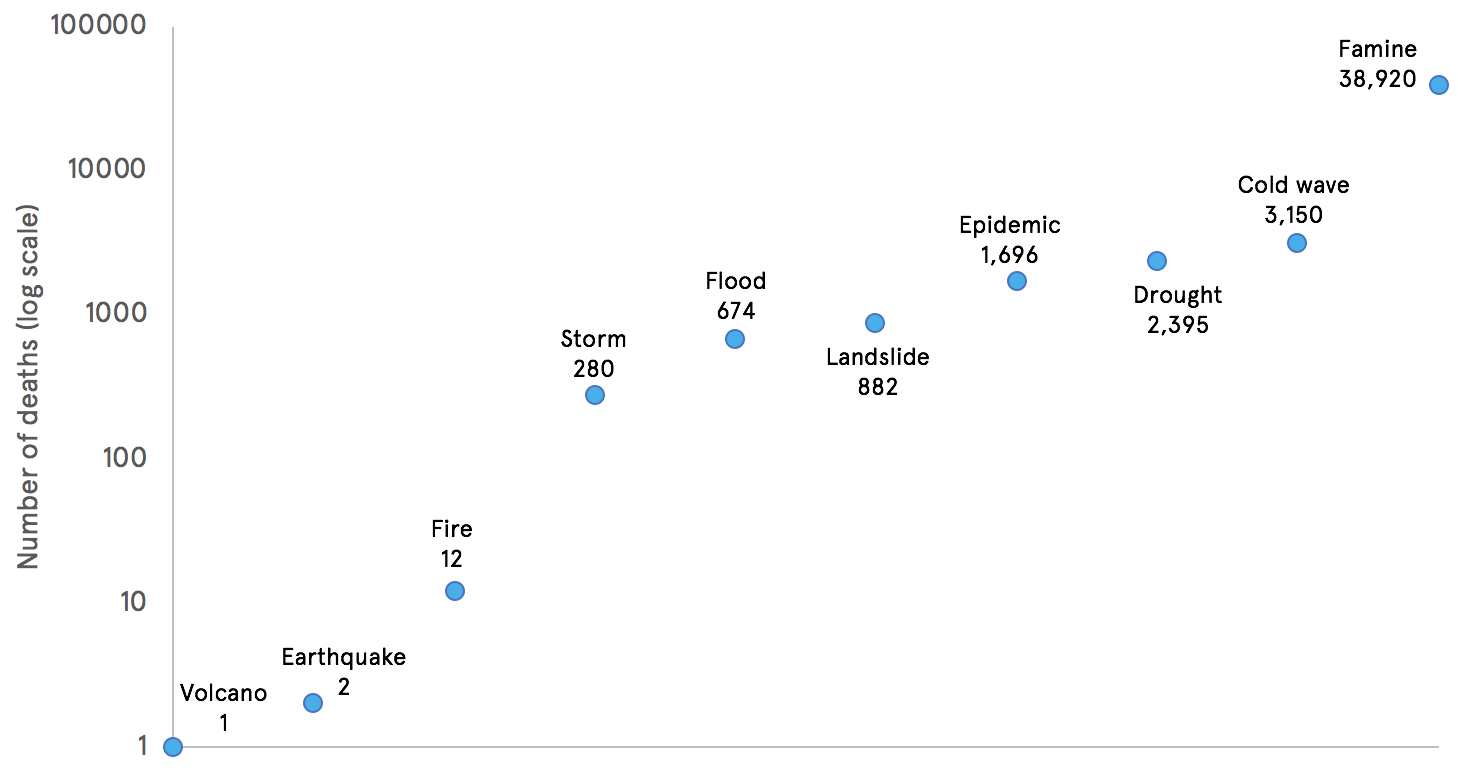

Availability bias also shapes media attention. A striking example of this, shown in Figure 1, is a study which examined the amount of television coverage given to 5,000 natural disasters over 1968 to 2002. It found that famines and droughts (gradual, centred on absence) required thousands of times more deaths than volcanoes and earthquakes (sudden, spectacular) to get the same level of coverage. If we assume that deaths from any type of natural disaster deserve equal attention, then this suggests we may not be focusing on where most good could be done.

Figure 1. Number of deaths needed to receive as much media attention as one death from a volcano

Adapted from Table 8

How do policy makers respond to shifts in attention? Organisations and individuals can only process a limited amount of information at any one time, so they need simple ways to filter, prioritise, and create agendas. This means that policy makers also use heuristics to guide their attention. For example, a study of senior ministers and party leaders from Belgium found that they ‘employ a number of rules of thumb to decide quickly about what matters and what not’.

If policy makers are also guided by heuristics, what are the implications? In many cases, the heuristics will work well. But the concern is that the availability bias may mean they ‘overreact’ when an issue suddenly attracts attention. This is where disproportionate resources are allocated to an issue, so that the costs outweigh the benefits (although this is a tricky judgement to make).

A well-known example of policy-overaction in the UK is the 1991 Dangerous Dogs Act, which was created in response to media perceptions that the number of dog attacks on humans had spiked, and the ensuing pressure for the government to act immediately. The legislation is not seen as a success, and in 2013, a government committee concluded that the law had “comprehensively failed to tackle irresponsible dog ownership”.

The flip side of overreaction is that issues that do not attract attention may experience ‘policy underreaction’, where harm is incurred through insufficient action. Indeed, some see this as a common cycle: government overlooks an issue, problems may build up, then attention suddenly shifts and the system scrambles to react. This underpins the apocryphal US saying that ‘Congress does two things well: nothing and overreacting’.

If availability bias makes policy makers overreact in response to shifts in attention, it may also affect what policy options they choose. In other words, policy makers may select a solution simply because it comes to mind easily. This can be because it is familiar (“what we always do”) or because it is currently popular (“what everyone else is doing”). Indeed, work in the USA has shown how state-level policy makers may be vulnerable to ‘policy outbreaks’, where they rapidly copy an initiative because they have noticed their neighbours doing it.

These types of decisions may well be good strategic and political ones. Policy makers may react “disproportionately” in order to signal leadership, or change the terms of debate in their favour. For example, Germany took drastic action to shut down its nuclear power stations in response to the 2011 Fukushima disaster. Arguably this was an overreaction, since the fundamental risks had not changed, and the industry employed 370,000 people. But part of the motive was likely to be political: taking dramatic action to try to “get ahead of the debate” and stem the political damage seen in recent state election results.

But if we put the political calculus to one side, we can see that availability bias can cause waste and even harm. That is why our Behavioural Government project will suggest ways of working round the availability bias to mitigate the problems it can cause.