This is the sixth blog in our Behavioural Government series, which explores how behavioural insights can be used to improve how government itself works.

The “illusion of similarity” is where policy makers have inaccurate assumptions about what people think or know, and inaccurate predictions about how people will act.

This can cause policy makers to think that more people share their own opinions or attitudes to an issue than is actually the case. Policy makers may over-estimate the public support for a policy as a result.

For example, an online study compared the personal support of Americans for three controversial policies to their estimates of public support for those measures. Respondents were asked to rate their support on a four-point scale (1 – oppose strongly, 4 – favour strongly) for a) teaching morality in public schools; b) the death penalty for those convicted of murder; c) registration and licensing of all new handguns sold in America.

Later, they were asked to estimate the proportion of US citizens that would favour these policies (1 – fewer than 20%, 5 – more than 80%; with 20% intervals in between). Figure 1 shows the results: for each of the three policies, the more respondents were in favour of a policy, the more they thought others were as well.

Figure 1: Personal views bias perceptions about public support for policies. Adapted from Wojcieszak and Price (2009).

Another problem is that the illusion of similarity can cause policy makers to overestimate how much people will understand or embrace a new policy. Policy makers, deeply immersed in the detail, may assume that the public will also pay attention to the policy, see what it is trying to do, and go along with it – none of which may be true.

A simple illustration of how we assume that other people will react the way we expect comes from a study where people tried to communicate well-known songs to others by tapping out the song’s rhythm. The group that were tapping out the song expected that listeners would get the song right 50% of the time; in reality, they only got it right 2.5% of the time.

Interestingly, this was not because people overrated their skill – the results were the same even if the person knew the tune but was watching someone else tap it out. People failed to recognise how different the listener’s situation or experience was from their own.

Similar failings happen in policy making (particularly when there is little external input to the process). A good example of misperceptions is provided by a recent study examining the power of defaults in education. This study randomly assigned parents of students to three different ways of signing up for an education-focused text message support system:

- Standard. Parents were sent a text message that they could adopt the technology by enrolling on a website (standard practice);

- Simplified. Parents were told by text message that they could sign up just by replying “Start”;

- Automatically enrolled. Parents were told by text message that they could opt out of the service by replying “Stop”.

The results show that there was an extremely strong effect from automatic enrolment: signup rates were 1% for the Standard group, 8% for the Simplified group, and 96% for the Automatic Enrolment group.

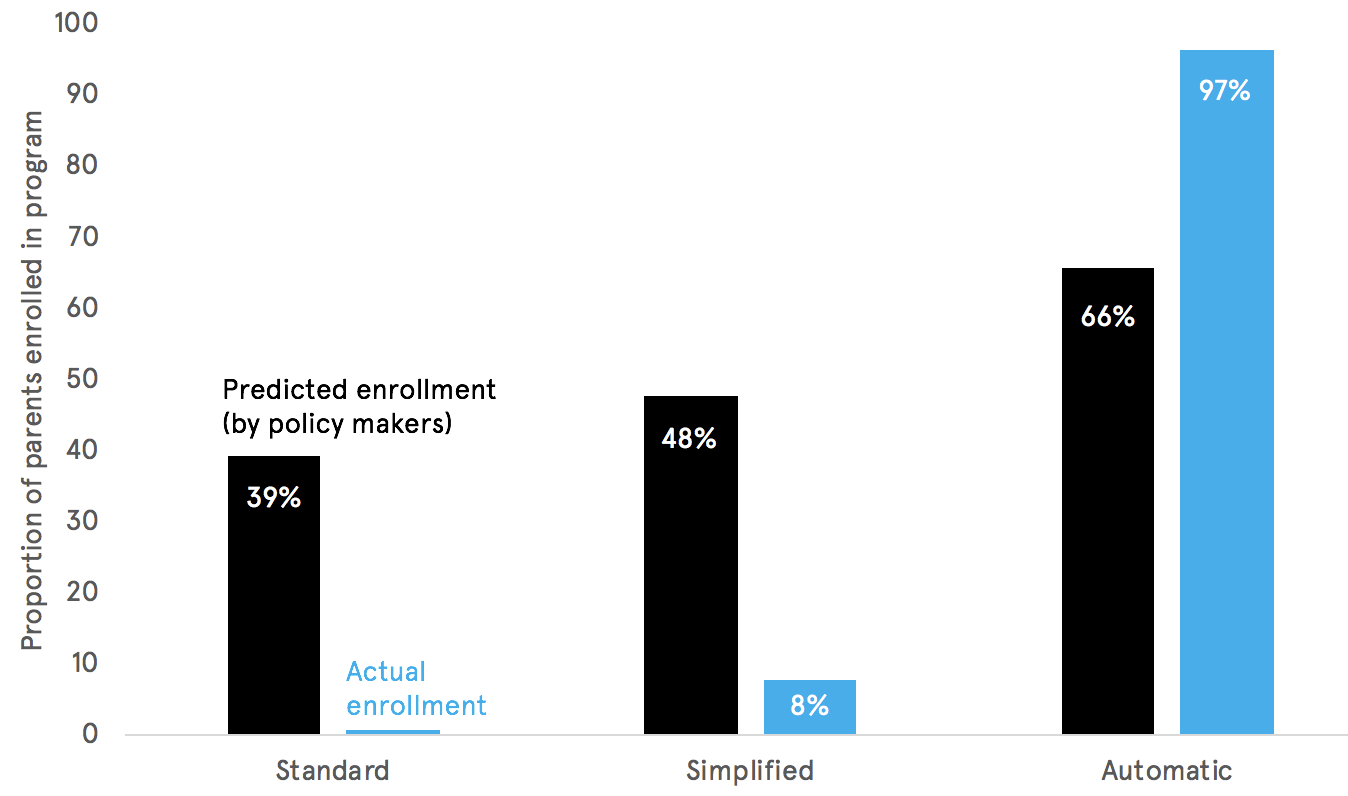

However, the study also asked 130 education decision makers (e.g. senior teachers and administrators) how effective they thought each approach would be. Figure 2 shows that the experts predicted uptake rates of 39%, 48% and 66% – a good deal off the true rates. For example, they overestimated the Standard group’s take-up rate by 38 percentage points and underestimated the effectiveness of the Automatic group by 31 points. This is not a trivial misperception: the Automatic Enrolment group ended up with higher test scores and a 10% lower rate of course failures.

Figure 2: Take-up of educational innovation versus take-up predicted by policy makers.

Our view on this study is that the decision makers overestimated how engaged the parents would be, and failed to see how they may not want to expend even a small amount of effort to sign up.

Indeed, we think that policy makers often over-estimate how much the public will engage with their initiatives. This may be because they have spent so much time thinking about the policy and discussing it with others in a similar position. We consider pragmatic ways of reducing this “illusion of similarity” in our upcoming Behavioural Government report, out in July.

Note: we have used the term “illusion of similarity” as a more accessible term for the concept of “naïve realism”.