Over the next few weeks, we will be highlighting some of our recent trials. This first post is dedicated to an emerging area of focus for BIT: home affairs and justice.

We occasionally get a result that even we are stunned by. One of these, picked up in the media coverage of our 2015 Update, is about police recruitment.

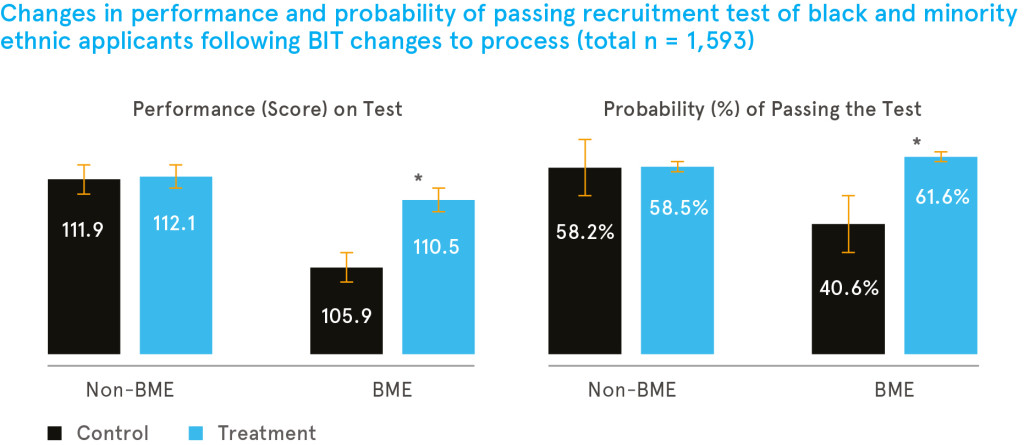

Working in partnership with Avon and Somerset Constabulary, this cost-less intervention dramatically increased the success rate of applicants from a black or minority ethnic (BME) background in a key part of the recruitment process.

What was the intervention?

The trial focussed on a stage in the recruitment process where we saw the greatest disproportionate drop in BME success – an online Situational Judgment Test (SJT). This is a multiple choice, online assessment which tests how would-be recruits might respond to real situations that officers have to face.

Candidates are invited to take the test by email, and our intervention added a few sentences to that email. The additional sentences prompted applicants to reflect on what might make them a good addition to the force, and what significance that would bear in their community.

Applicants were randomised into two groups. Importantly, randomisation was stratified so that there were similar numbers of BME and non-BME applicants in each group. The control group received the email that Avon and Somerset Constabulary was already planning to send. The treatment group received the adjusted email. The outcomes measured were the raw score on the SJT, and the probability that an individual would pass to the next stage in the assessment process.

What was the result?

The intervention positively affected both outcome measures for BME applicants, but, interestingly, had no effect applicants from non-BME background. The BME applicants who received the adjusted email scored significantly better on the test than the BME applicants who received the business as usual email. On average, they scored five points higher which translated into a significant increase in the probability that they passed this stage of the assessment process (an increase of 20 percentage points). Effectively, this intervention closed the gap in probability of passing the test between BMEs and non-BMEs.

How did we decide what to do?

Evidence from the behavioural literature suggests that priming, and stereotype threat, can have strong effects on performance. Telling an individual before they take a test that BME test-takers do poorly, for example, has been shown to decrease performance almost immediately (Steele & Aronson, 1995). In contrast, there is some evidence that this negative effect can be reduced with different types of “positive priming.” For example, when American college students were asked to write about their values for 10 to 15 minutes at two key moments during an introductory biology course, this narrowed the performance gap between first-generation students and continuing-generation students by 50% and increased retention in the next level course by 20% (Harackiewicz et al. 2013).

What might be driving this effect?

Our analysis showed that there was no difference in how long people take on the test (so we probably haven’t increased reflective deliberation). We think it’s about feeling more comfortable with your gut instinct.

The Situational Judgment Test itself splits its questions into four categories, based on the competencies that are meant to be tested: communication and empathy; customer focused decision making; openness to change and adaptability; relationship building and community.

Of these four areas, the effect seems to be driven by the first two: communication and empathy, and customer focused decision making. Given the nature of the intervention, this makes sense: we primed individuals to imagine themselves as a police officer. It is possible therefore that our intervention is helping BME applicants go with their gut instinct when answering questions, rather than with what they expect the “correct” answer to be. If this is true, we should not expect an effect on applicants’ levels of adaptability, and indeed we do not see an effect in this category. With regards to questions on relationship building, the direction and size of the effect is in line with our hypothesis, but the coefficient just misses the cut-off for statistical significance at the 10% level (p-value of .105). Thus, it is difficult to interpret this result further.

What next?

As reported in our 2015 update, we’re excited to have started large programmes of work with two police forces – West Midlands Police and Avon and Somerset Constabulary – which will deliver up to 10 RCTs over the next 18 months. More excitingly, we will soon be able to announce projects with other Police forces across the country.

Forthcoming trials will focus on: police morale; police efficiency; demand management; online exploitation of adults and children; and reoffending.

Beyond policing, we are now working on a range of Home Affairs issues, like illegal immigration and illicit working, smoothing passport demand and reducing witness attrition prior to trial.

For those of you coming to BX2015, be sure to visit our Home Affairs session, where you’ll be able to hear from Prof Lawrence Sherman, Prof Angela Sasse, Chief Superintendent Alex Murray, Daniel Effron, and our very own Simon Ruda. You can also catch our partner for this police recruitment trial, Chief Superintendent Ian Wylie, at the session on behaviour change at work.

Project team:

Elizabeth Linos, Senior Advisor

Joanne Reinhard, Advisor

Simon Ruda, Principal Advisor, Head of Home Affairs, Security and International Development