Today we publish a major report detailing the results of our Financial Capability Lab partnership with the Money Advice Service (MAS) and Ipsos MORI. Some of the early Lab results exploring how credit card terms and conditions could be better explained to customers were published in the Government’s recent Consumer Green Paper.

The report we are publishing today provides early stage insight into how a behavioural approach could help people to repay their debts faster, to save more, and to seek financial guidance at key moments. Whilst the lab results show significant potential, we need your help to test them in the field. If the ideas continue to show promise, we will seek to deploy them at scale to make a real difference across the UK.

Here are some of the most exciting ideas.

Can we reduce the cost of credit card debt using an interface informed by behavioural science?

Previous research has shown that information about minimum repayments on credit card statements can act as a strong anchor1. This means that many of us will be unduly influenced by the low minimum repayment figure shown on credit card statements, reducing our repayments and significantly increasing the amount of interest we pay on our credit card debts. We tested a repayment interface informed by behavioural science to see if we could reduce the impact of the minimum repayment anchor and increase overall repayment amounts.

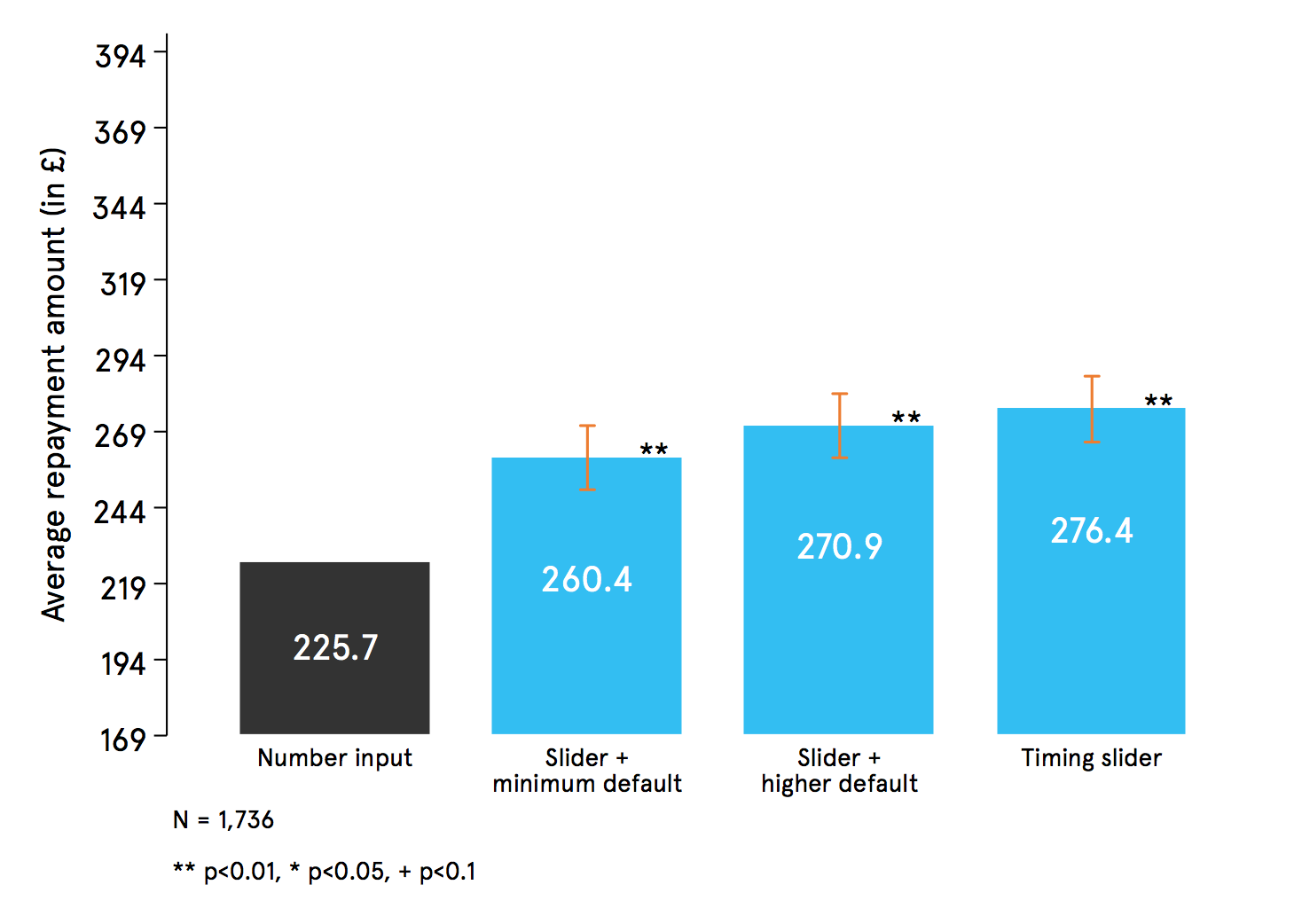

The main component of our interface was a slider. Sliders are used across the financial services sector, often to help consumers decide how much they would like to borrow. Using our online testing platform Predictiv, we tested three different slider interfaces against the current industry standard (a box to enter the desired repayment amount). Our results show significant increases in average repayments for all of the slider interfaces that we tested. Read more about the test and next steps in the main report on pages 21-23.

Figure 1: Effect of slider interfaces on repayment levels (stage 1: hypothetical choice2)

Can we use our social networks to help us save?

BIT, in collaboration with researchers from Harvard University, have been running a successful ‘Study Supporter’ programme using peer support to improve student retention and success in Maths and English. In the Lab, we adapted ‘Study Supporter’ into a new programme that encourages people to set savings goals and stick to them by inviting someone they trust to become their ‘Savings Supporter’. Read more about how this idea can help people to overcome barriers to discussing personal finance in the main report on pages 44-45.

Could the supermarket checkout be a good place to get in the habit of saving?

The checkout or payment stage of a transaction is a moment at which people may already be considering the consequences of regular purchases for their personal finances. To harness this type of thinking we designed timely prompts for shoppers to encourage them to save a small amount, and tested these in an online shopping simulation using Predictiv. If people had accrued savings during the shop through discounts and special offers, we asked them whether they would like to ‘bank’ these savings. We see significant potential for ‘checkout savings’ prompts to encourage people to save regularly. Read more about how many people chose to save in our simulation in the main report on pages 34-35.

We have been delighted by the breadth and depth of interest in our Financial Capability Lab partnership so far. Academics, civil servants, representatives from financial institutions and fintech companies, debt advisors, and many more helped us to develop these ideas based on insights from behavioural science. If you would like to find out more about partnering with us to test these ideas in the field, please contact us. Whether you want to join our partnership, contribute your own research, or contribute to the wider policy conversation, we look forward to hearing from you.

1 Stewart, N. (2009). The cost of anchoring on credit-card minimum repayments. Psychological Science, 20(1), 39–41.

2 This experiment had two stages: first participants made a hypothetical choice about what they would do if they were in the scenario described in the experiment, and then they were incentivised by paying participants based on their ability to find the correct repayment amount (what they ‘should’ do).