On 4 May 2000, millions of computers were infected with a virus that erased enough files to cause around £12bn worth of damage worldwide. An email virus that appeared to be a love letter from a friend. The message read:

Subject line: ILOVEYOU

Body of email: Kindly check the attached LOVELETTER coming from me.

Attached was what appeared to be a text file named “LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.” The attachment was in fact a harmful virus that liberally erased computer files before spamming victims’ contacts with the same message.

The Love Bug was very much a phenomenon of its time. Spam filters and antivirus software were unsophisticated, malware was almost unheard of and as such, we weren’t particularly suspicious of digital communications. And yet phishing emails – malicious emails designed to trick us – haven’t disappeared. Rather they have evolved. Where once was a curious love letter or a bizarre business offer, phishing is now highly targeted (otherwise known as ‘spear’ phishing). Emails now use specific information that we leave online via social networks or company websites (e.g. name, organisation) and information about familiar individuals (e.g. colleagues) to create an impression of authenticity and achieve their ends.

The evolving sophistication of phishing methods prompted us to create a database of nefarious emails. We are using it to map out the most prevalent social engineering techniques – the use of deception to manipulate individuals into divulging confidential or personal information – in use online today, in the hopes of preventing future victimisation to these schemes. Here’s some common phishing tactics to watch out for:

Impersonating a legitimate contact

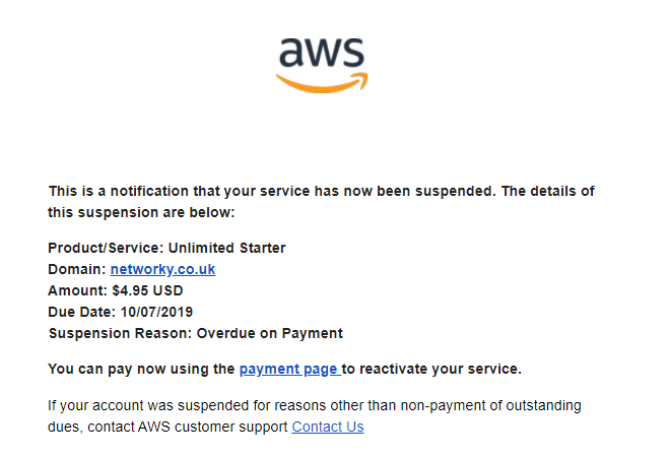

Phishing emails almost always employ social disguises whereby attackers masquerade as legitimate organisations or contacts that we trust. Take the following phishing email received by our Technical Lead:

Subject line: Your service has now been suspended

Its likeness to Amazon Web Services – a trusted cloud-computing platform – is undeniable. In fact phishers will go out of their way to exploit our tendency to pay too much credence to the appearance of things by using the visual cues of a legitimate sender or purchasing domains that are similar to real domains such as ‘mazon.com’ or ‘amaz0n.com’.

Pretending to be a person in authority

Linked to impersonation is the use of authority to gain compliance. Evidence suggests that people are more likely to comply with a request when it comes from an authority figure. Phishing messages are routinely signed off as being from senior individuals such as a ‘bank manager’ or ‘head of human resources’ or ‘commander in chief’. Or our CEO:

This is an even more targeted version of spear phishing – ‘whaling’. Whaling attacks are well-researched and detailed messages directed at senior individuals (‘whales’) within an organisation. It is thought that these authority cues are effective because the request is not only viewed as coming from a reputable source, but we also fear being punished (by the authority) for failing to respond. For instance, in 2016, Snapchat reported that an employee had accidentally revealed payroll information of Snapchat employees after receiving an email purporting to be from Snapchat’s CEO.

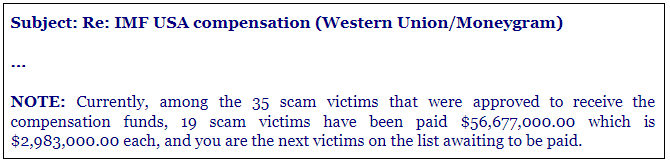

Telling victims that everyone else has already done it

We are more likely to cooperate when we believe that the majority of our peers have also done so. Phishing messages using social norms often mention that other members of a group have already complied e.g. “80% of your fellow employees have already signed up”. And because we are particularly likely to rely on social norms as an indication of the correct course of action in times of uncertainty, these techniques can be very effective. For instance a member of our team was led to believe they were in the minority of fraud victims to not be reimbursed:

Making victims excited or scared

The role of affect (mood, emotion) in decision making has been well explored. High levels of emotion (e.g. hunger, anger, pain) can induce what is known as a ‘hot state’. These ‘hot states’ impair our ability to think rationally and may cause us to behave impulsively. Phishers may, for instance, use the promise of a monetary reward or an attractive prize to provoke an emotional response such as excitement within their victim. Alternatively, they may use urgency cues to create a sense of fear and immediate threat. The example below perfectly captures these techniques:

Phishing messages are frequently framed as requiring urgent action, for example: “Your account will be deleted unless you verify your details” or “Someone had your password”. These excited or fearful ‘hot states’ increase our risk of behaving irrationally and impulsively and thus may make us more likely to disclose personal information.

So what can be done to protect us from online scams and phishing emails? Technology is the first layer of defence against these types of threats. The advancement of cyber security technologies and their increasing employment across organisations and platforms provides us with an initial veneer of protection. However, technology cannot, in itself, be our ultimate safeguard online. Rather it must work in tandem with the individuals it is designed to protect. That means we, as behavioural scientists, must identify our cognitive biases, evaluate how they are being exploited, and use this knowledge to thwart criminal activity.