Physical punishment — from hitting children with sticks to making them kneel to slapping them — occurs every day in classrooms throughout the world. Yet we know experiences of violence at school are linked to lower attendance and academic achievement as well as higher drop-out rates. In turn, lower educational attainment rates among girls can have effects across generations, leading to a weakened household economy, worse health, and higher fertility rates.

“Now I have the fear of learning.” — Congolese student (after experiencing corporal punishment in school)

Despite the detrimental impacts and staggering rates of corporal punishment in schools, little is known about how to shift the harmful attitudes and behaviors that uphold these practices, particularly in crisis-affected contexts. Even when interventions are proven effective — for example, the Good School Toolkit created by Raising Voices in Uganda reduced the risk of physical violence by school staff against children by 42% — we often don’t know which part of the program contributed to the improvements. Meaning, there is virtually no evidence on effective ingredients and approaches to reduce physical punishment in schools in humanitarian settings.

The Behavioral Insights Team (BIT) and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) are therefore exploring whether applying insights from the behavioral sciences — or the study of how people make decisions and why — can shed some light on this issue. So far, the results are promising. Our first in a series of iterative trials has shown which messages are most effective at shifting teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about corporal punishment. Next, we will build on this learning to design a program aimed at improving teachers’ self-regulation, wellbeing, classroom management, and use of positive discipline strategies rather than physical punishments. In this post we outline these findings and next steps.

Why are teachers using corporal punishment?

Our work takes place in Nyarugusu Refugee Camp in Tanzania — the third largest refugee camp in the world and home to nearly 140,000 refugees from neighboring Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Through interviews, group discussions, and observations, we learned that many teachers living in Nyarugusu viewed physical punishment as a way to prepare students for adulthood, teach them to respect their elders, and guide them to a better future.

“[Harsh discipline] helps children change and become better students because they are afraid of doing it [misbehaving] again.” — Congolese teacher

What can we do about it?

A behaviorally-informed approach would typically tweak the environment in which people make decisions to encourage a change in their behavior. As people begin to change their ways, they experience cognitive dissonance (or a discrepancy between their actions and beliefs) that prompts them to justify their new behavior. In this process, people tend to adjust their old beliefs.

In this case, we faced teachers who seemed reluctant to change their views or their behavior. So we designed a randomized controlled trial to explore whether leveraging behavioral insights could help reduce favorable attitudes towards corporal punishment. Our trial compared three approaches, one strategy often used in the violence-reduction field (a rights-based approach) and two approaches drawing on behavioral insights.

Both of the behaviorally-informed groups were also exposed to messaging promoting a growth mindset — a belief that people’s traits, such as intelligence and abilities, can change with effort — and asked to complete an exercise contrasting their new understanding of corporal punishment with their self-image (as protectors of children, for example).

Before engaging with this content, teachers in the empathy building and clinical evidence groups were also asked to reflect on their values and identity (by selecting two to three values from a pre-selected list and writing about how they exemplified these values in their lives). Previous studies have shown that such simple values-affirmation exercises can actually make people more open to accepting new information and to changing their views, while boosting their self-efficacy — i.e., confidence in their abilities to accomplish tasks.

To assess the effectiveness of these three approaches (right-based, empathy, and clinical messaging), we offered teachers in each group the option of signing up to receive more information about how to make their classrooms safe. We also asked teachers some questions to gauge their attitudes towards the use of corporal punishment in schools.

What worked?

To our surprise, on average, none of the approaches were more effective at encouraging sign-ups to receive additional information. We found that speaking about the rights of children and the rules that protect them did encourage visible signs of compliance (i.e., enrollment in a program) among certain vulnerable populations though. This is potentially due to the fact that a more institutional or familiar message — focused on rights, laws, and expected conduct — may prompt more people to signal they are in compliance with such rules.

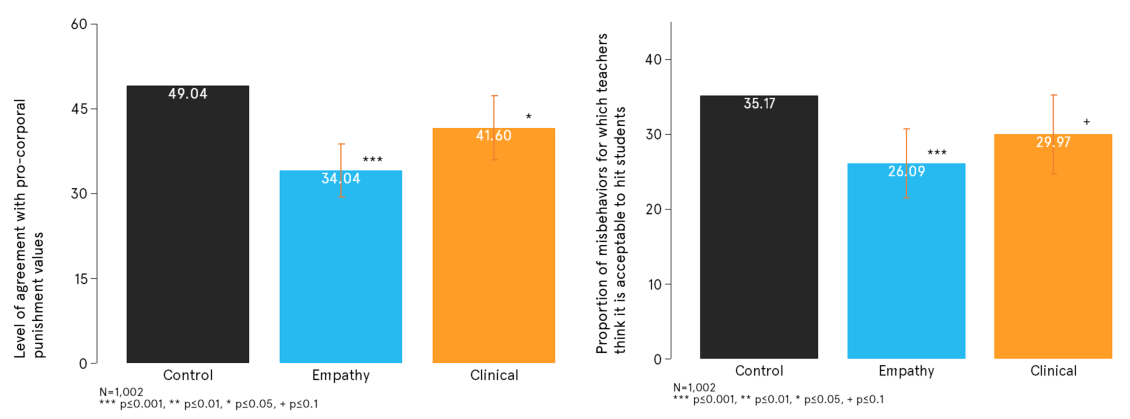

This strategy of highlighting rules and rights, however, was not effective in the key outcome of reducing favorable attitudes towards the use of violence against children. Instead, empathy-building exercises that asked teachers to take the perspective of children were most effective at shifting teachers’ opinions, from supporting the use of corporal punishment in schools to disagreeing with it. In fact, engaging with the empathy-building content reduced teachers’ level of agreement with corporal punishment by 31% (using a survey measuring values) and decreased the number of situations in which teachers think that hitting children is acceptable by 26%. Sharing clinical evidence on the negative effects of violence against children was also more effective than the rules and rights-based approach at shifting favorable attitudes towards corporal punishment, albeit to a lesser extent than empathy-building.

Figure 1: Effect of behaviorally-informed messages on teachers’ attitudes towards using corporal punishment (using a values-based and a scenarios-based surveys)

Lastly, reflecting on values and identity increased teachers’ sense of self-efficacy by nearly 10%, which evidence suggests could yield a number of positive outcomes for children, including improved learning outcomes.

What’s next?

The IRC and BIT will build on the learning from this study to design a light-touch, tailored program to prevent and reduce the use of corporal punishment in Nyarugusu, targeting behaviors as a starting point. We will invite teachers to participate in self-guided group sessions inspired by cognitive behavioral therapy — an approach that has been effectively applied to many problems, from reducing destructive behaviors to improving mental health — to help them challenge thinking and patterns of behavior related to using violence. As part of these sessions, we will provide teachers with alternatives to corporal punishment, behaviorally-informed tools — such as planning exercises and timely reminders — and the social support they need to form new habits. Based on our findings, this program will also feature empathy-building exercises to increase teacher’s willingness to change their disciplinary methods.

Insights from this trial also highlight the importance of rigorously testing different approaches to learn what’s most effective. In this case, we learned that discussing rights and norms may prompt people to signal compliance (with those rules and norms); so this may be an effective way to encourage one-off actions — like signing up for a program. Once people’s attention is engaged, however, building empathy or even speaking about the potential damage of violence against children may be better strategies to start generating social change to protect children in schools.

This experience reinforces our commitment to evaluate the impact of programs as they are being designed, ensuring we craft solutions based on evidence of what works to prevent and reduce violence against children in schools.