Replication is important to scientific progress, but is not always seen as the most exciting area for researchers. In this blogpost, we discuss a recent New Zealand project on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in which we have replicated the fundamentals of a previous BIT intervention, but have also used the opportunity to learn more about the way in which the intervention can have impact. Readers will have to wait for a forthcoming academic paper for a detailed discussion of the results, but we think that it is important to put a spotlight on the importance of contextualising results.

COVID-19 has drawn the world’s attention, but AMR was named as one of one of the top ten threats to global health by the World Health Organisation in 2019. The problem of AMR is not going away and urgent action is needed, with a recent report warning that 10 million people could die from drug-resistant diseases each year by 2050 if the status quo continues. In fact, the WHO have flagged the continual threat of AMR after the pandemic. New Zealand had the fourth highest antibiotic use in the OECD in 2017. Yet there are unique challenges in New Zealand, where Māori and Pacific people are at higher risk of infectious diseases and experience worse health outcomes in general. Therefore, they may need more antibiotics.

This raises the question: how do we reduce antibiotic overuse without worsening health inequities?

What did we already know?

We already know about effective interventions to reduce antibiotic prescriptions. In the UK, we sent a letter to high-prescribing practices informing them that they were in the top 20% of prescribers in their area. The intervention was a success, and made a big dent in the UK government’s targets to reduce antibiotic prescribing.

This original trial showed that using social norms can be effective. However, the letter included a number of other elements, which were tested jointly with the social norms. Therefore, we were not able to see whether or not the norms were the most effective component.

This was replicated in Australia by the Behavioural Economics Research Team in the Australian Department of Health (BERT) and the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian government (BETA). They innovated by sending letters to individual doctors, but also tested different versions of the letter, which allowed them to see if it was the norms on their own that were having an impact.

This trial confirmed that the inclusion of norms was the key active ingredient. However, questions still remained as to the impact of the intervention on health equity. It was not clear as to whether the letter meant that GPs stopped prescribing to certain groups, or whether they just cut down the number of prescriptions to each group equally.

Building on the results in New Zealand

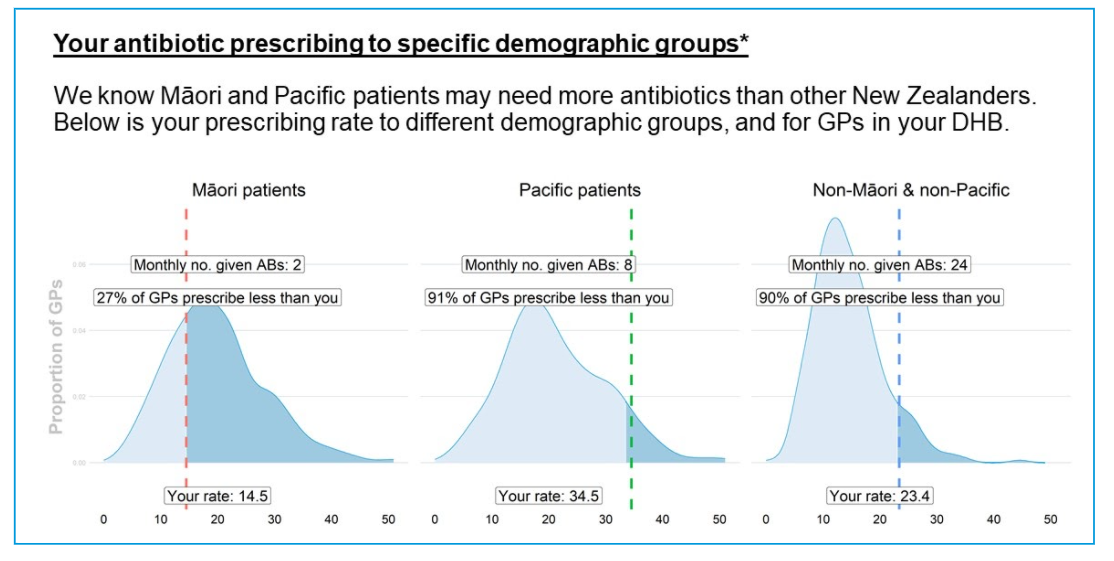

In New Zealand, we have built on the British and Australian trials, with a particular focus on encouraging appropriate prescribing to Māori and Pacific patients. We used the fundamental theory of the British and Australian trials by sending a letter to the top 30% of prescribers in each region, and targeted individual doctors with a graph on their prescribing and the specific antibiotics included on the back page. Our innovation was to include graphs showing the GP’s prescribing to Māori, Pacific and all other patients. We designed this as a wake up call to any GP who was a high prescriber overall but a low prescriber to Māori or Pacific patients.

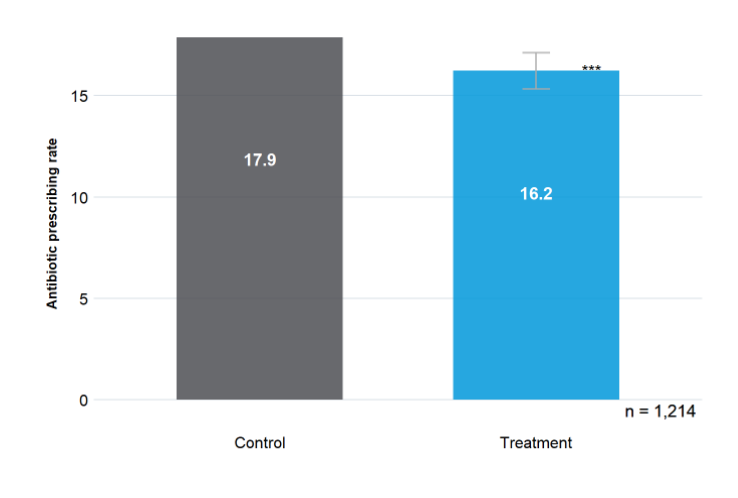

Effect on the antibiotic prescribing rate

Tested with a randomised controlled trial, our letters reduced prescribing by 9.2% between September and December of 2019. Furthermore, when we tested the impact of the letter on GPs who were high prescribers overall but low prescribers to Māori or Pacific patients, we find potential (though not statistically significant) evidence that the intervention may have actually increased prescribing to Māori or Pacific patients, thereby potentially reducing inequities. Where GPs overprescribed for Māori or Pacific patients we found that the letter led to a significant decrease in prescribing. This draws attention to the need to consider equity in any of our behavioural interventions.

This trial shows how replication can have social impact on a global threat to health, but also help us generate new insights of an intervention and uncover new areas for investigation. In particular, we can use a tailored intervention with social norms to simultaneously address over- and under-prescribing.

This project was funded by the Health Quality and Safety Commission and Pharmac. We would like to thank Catherine Gerard, Janet Mackay, Rawiri McKree Jansen, Richard Hamblin, Sally Roberts, Leanne Te Karu, Aniva Lawrence, Jan White and Nikolai Minko for their support and expert advice.