In 1997, leaders from Cardiff’s local authority, police, city licensing regulators, an emergency department and a local university met to discuss a problem. Violent crime was increasing in the city at a disturbing rate. Something had to be done.

Seven years later, violence-related hospital admissions were down by 35% and serious violence by 42%. Estimates of the annual saving caused by the decline in violence amounted to £7m per year. Meanwhile, in similar cities, violence increased.

Public service leaders in Cardiff worked together, sharing data anonymously from emergency departments on where violence was occurring and introducing changes such as plastic glasses in bars and pedestrian areas in trouble-spots. They achieved remarkable success, all borne out of local leaders taking action and solving a common problem.

Today, the Chancellor announced a new Centre for Public Services Leadership. Its goal is to further develop leaders and collaboration across the public service. It aims, in other words, to help public service leaders innovate and develop new ideas to tackle difficult challenges – just like the successful ‘Cardiff Model’.

Over the last six months, we’ve been supporting the Centre’s Taskforce to look at the evidence for the impact of leaders in the public service and what works for developing public service leaders. Today, the Taskforce released our report based on a review of the literature on public service leadership and interviews with 50 public service leaders.

Public service leaders matter for their organisations and community

Leaders make a real difference to their organisations and the community. The ‘Cardiff Model’ would not have succeeded without the initiative and collaboration of public service leaders. In education, high-quality leadership and management is positively correlated with higher test scores. The What Works Centre for Wellbeing found effective leaders and managers in NHS Trusts increase the likelihood of high patient and staff satisfaction.

One study of a services firm found replacing a poor team leader with a good one increased productivity by 13%, whilst a structured programme of peer learning for leaders in the private sector increased revenue by 8.1%. In our interviews, the impact of poor leaders was of particular concern with one chief executive of a services agency suggesting a poor leader could “throttle a whole organisation without much effort.”

To be sure, leaders are one factor that sit alongside others such as strategy, governance, pay and reward, learning and development and recruiting. However, we conclude the weight of evidence, including several randomised controlled trials focused on improving management and leaders, suggests the presence of effective public service leaders is associated with improved organisational performance and employee wellbeing.

Leadership can be taught

Our review of the leadership literature found structured leadership development programmes, peer learning and feedback (including positive feedback from the community) can improve leaders.

In Texas, for instance, a randomised controlled trial tested the impact of 300 hours of training on ‘lesson planning, data-driven instruction, teacher observation and coaching’ across two years on a small sample of principals. It finds, for principals who stay in post over the course of the trial, an increase in student achievement from training. The author concludes the return on investment of leadership and management training for pupils is greater than lowering class sizes, charter school programmes or Teach for America.

Of course, not all leadership programmes are created equal. We concluded interventions to develop leaders can work but they must be carefully constructed. Specifically, they should account for culture and context, offer practical insights and focus on behaviour change before, during and after any training or intervention. Finally, much of the existing evidence on the role of leaders in the public service comes from international, rather than UK, examples. Therefore, the Centre should evaluate its interventions in the context of the UK public service.

Encouraging the adoption of simple practices could help public service leaders

A general weakness of the public leadership literature is it often leaves practitioners confused about the specific steps for leadership success. This is, in part, because of the diversity of our public service in terms of services and demands.

However, beyond broader leadership development programmes, observational evidence suggests there may be specific practices that can help public service leaders. A non-peer reviewed analysis of more than 150 headteachers in the US found having three individuals who act as ‘lifelines’ during challenges and taking time to renew (and turn off the phone at the end of a day) are associated with longevity in position. An analysis of 411 leaders in UK academies found establishing clear links with other public services alongside spending time in the private sector are associated with better headteachers.

Given these emerging – but still largely untested – associations we think there is room, whilst acknowledging the diversity of experiences in the public service, to experiment with building, and evaluating, a toolkit of the specific practices of effective public service leaders.

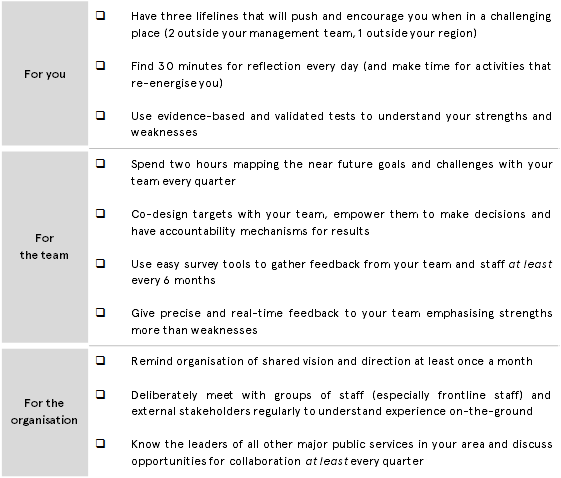

For instance, the impact of practices that show promise (examples presented below) could be evaluated in the context of the UK public service. Over time, as evidence is gathered, the Centre for Public Services Leadership could develop a toolkit of useful, specific and pragmatic practices that are immediately useful for UK public service leaders.

Example practices for evaluation in the context of the UK public service

Ultimately, based on our interviews and literature review, we found a gap exists for a central hub for cross-service peer learning and leadership programmes alongside cutting edge evidence on ‘what works’ for developing public service leaders. The Centre for Public Services Leadership could fill that gap, spur the creation of more initiatives like the ‘Cardiff Model’, test new approaches to developing leaders and make a real difference for public services and citizens across the UK.

If you’d like to know more, read our report or contact robbie.tilleard@bi.team