There are an estimated 11.5 million migrant domestic workers (MDWs) working for households around the world, according to estimates by the International Labour Organisation (ILO). In Singapore, over 245,000 MDWs live in their employers’ homes and perform household labour such as cleaning, cooking, and caregiving.

Incidents of abuse and harassment at workplaces are difficult to catch even when they happen in public places such as an office. When one lives with their employer as MDWs do in Singapore, the risk that abuse goes undetected is compounded. While there are measures in place to guard against abuse, including compulsory medical check-ups and house visits, empowering MDWs to seek help in case of abuse is of utmost importance.

The point at which one seeks help is almost as important as whether one seeks help at all. In the most extreme cases, MDWs might wait until their abuse escalates before seeking help. In many other cases, MDWs may have started out with small problems that snowballed into something much more difficult to solve because they were never addressed when it first happened.

We partnered with two non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) and Foreign Domestic Worker Association for Social Support and Training (FAST) to encourage domestic workers to seek help earlier.

We had 2 aims:

- to understand the different types of help-seeking behaviour that MDWs could undertake, and;

- to identify the barriers and enablers to help-seeking among MDWs.

What we found

MDWs utilise various channels to seek help, ranging from the informal (e.g., asking friends or family for advice) to more formal measures (e.g., NGOs, employment agencies, Ministry of Manpower, and police). In an ideal world, we might imagine that MDWs should seek help from informal channels for small problems, and escalate their help-seeking as their problems become more severe.

In reality, we found that MDWs mostly sought help through informal channels, and they only accessed more formal channels when encouraged by informal contacts (e.g., their friends prompted them to approach an NGO for help) or when they were desperate (e.g., they called the police when they did not know what else to do).

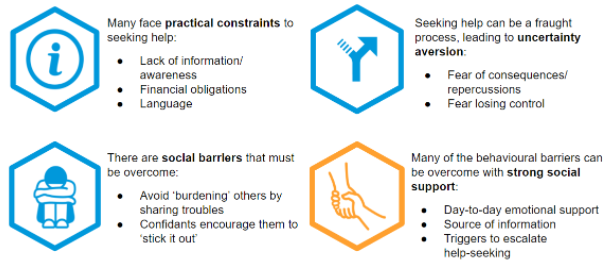

There were several barriers stopping MDWs from accessing more formal support:

| 1. Practical constraints. Sometimes, MDWs were not able to seek help even if they wanted to because of reasons such as: language barriers; financial obligations (MDWs could not afford to jeopardise their employment), or; lack of awareness (MDWs have low awareness of workplace entitlements) | “I was afraid that if I did something wrong, I would be sent back home. If that happened, how will I pay for my son’s education and pay back my loan?” |

| 2. Social barriers. We found that MDWs had a strong norm for dealing with their troubles privately. People self-censored because they did not want to burden others. | “Everyone has their own problems, you must learn to deal with yours.” |

| 3. Uncertainty aversion. MDWs often experienced status quo bias because the consequences of help-seeking were unknown — seeking help might make the current situation worse if their employer found out, and/or if they changed employer, the next employer might be worse. | “If people say they want to change employer, I will tell them: You know this employer — but do you know the next one? This employer scold you, but maybe the next one will beat you.” |

| On the other hand, we found that having social support was a huge facilitator to encouraging MDWs to seek help. Support networks facilitated access to formal and informal help-seeking avenues, and provided encouragement and reassurance to start the help-seeking journey. | “That lady helped me by calling the agency. When she said many people who work for my employer don’t stay very long, I had the confidence to leave instead of serving out my contract.” |

The intervention

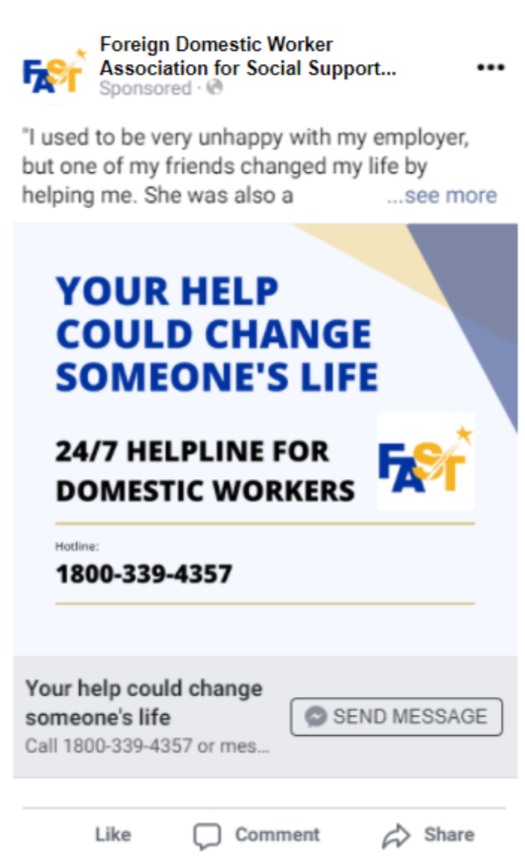

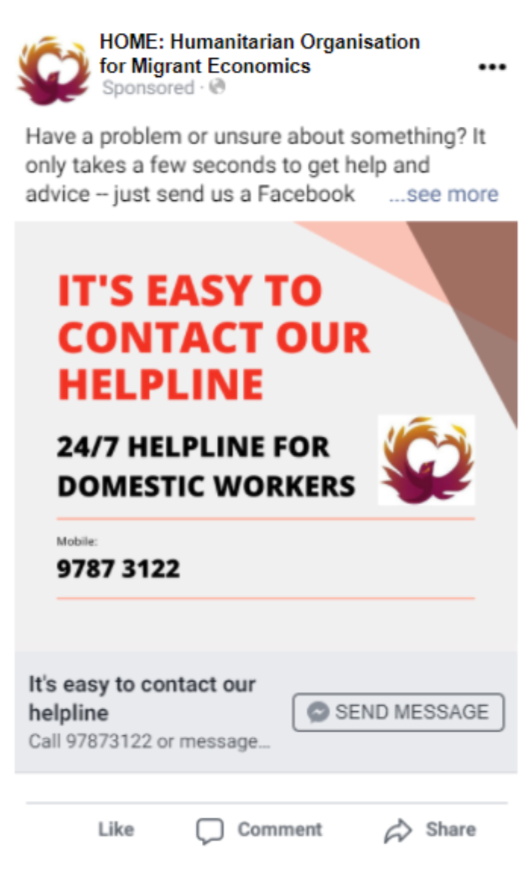

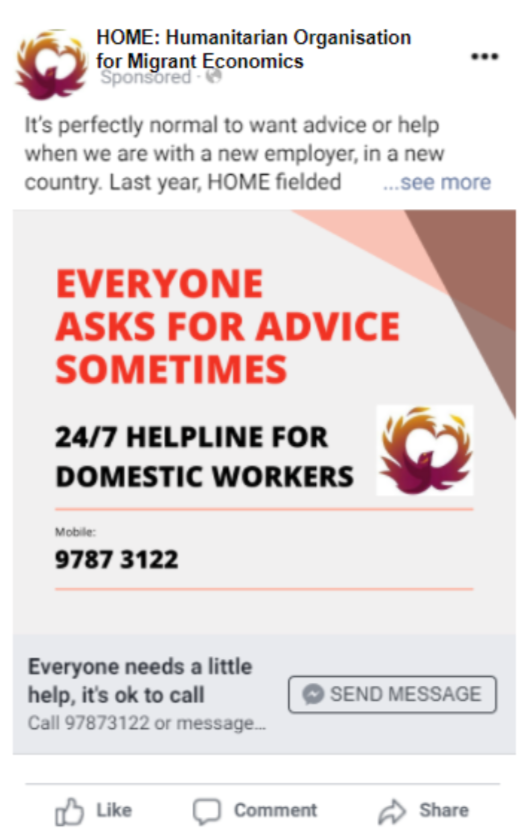

We then worked with the NGOs and MDW volunteers to design potential interventions to encourage MDWs to seek help by calling NGO helplines. Here we developed 6 prototypes for Facebook advertisements that would be run by the respective NGO Facebook pages:

| Easy (Bystander) | Inspirational story | Easy (MDW) |

|

|

|

| Address uncertainty | Social norms

|

Call earlier |

|

|

|

We eventually chose the 2 highest-ranking of these prototypes (based on MDWs’ rankings of what they thought was most likely to work) to test against a simple control in our trial.

Stay tuned for Part 2 next month to find out which prototypes we tested and how well they performed!

For the full version of our Explore results, click here.