With bricks-and-mortar shops shuttered by the pandemic, a record 85,000 UK businesses launched an online store or joined an online marketplace in the four months to July 2020. As a result, it has never been more important for businesses to adopt basic “cyber hygiene” controls, including keeping their software up-to-date or “patching”.

It’s hard for businesses — particularly SMEs — to know when and how to patch their software. In collaboration with the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB), we ran two trials to help tackle this problem. The first trial encouraged businesses to sign up for a free website security scan. The second encouraged businesses that signed up to patch any vulnerabilities we detected, and provided advice on how to patch.

We found that:

- Overall very few businesses (<1%) signed up to get a free website security scan. This suggests that cybercrime isn’t very high up on small businesses’ list of priorities. Automatically scanning businesses’ websites and alerting them to any vulnerabilities may be a more effective approach.

- More businesses engaged with the website security scan offer after seeing a regret aversion message — “What would happen if your website was attacked?”

- Businesses patched their websites after receiving vulnerability alerts. This suggests that a simple website vulnerability alert service could improve cybersecurity for small businesses.

Trial 1: Encouraging businesses to sign up for a free website security scan

In our first trial, we collaborated with the FSB to encourage their members to sign up for a free website security scan from the NCSC. To do this, we included the website scan offer in one of FSB’s weekly newsletters sent out to more than 85,000 members.

We tested three different messaging frames:

- Basic security (control message) – “Check the security of your website”

- Regret aversion (see Figure 1) – “What would happen if your website was attacked?”

Cyber security communications often focus on the negative outcomes of inaction, trying to scare individuals into taking action (or buying a product). We wanted to test a gentler, more empowering version of these traditional fear-based tactics. When making a decision, we are often ‘regret averse’ – we anticipate the regret we might feel if we do or don’t take a specific action and choose the option that minimises that anticipated regret. We wanted to test a message encouraging business owners to think critically about the risks facing their business and potential consequences of an attack. - Physical security metaphor – “Helping you find the chinks in your website’s armour” Metaphors can make it easier to understand complex threats. Physical security metaphors are particularly popular in cybersecurity and have been shown to increase comprehension of warning information.

Figure 1. Screenshot of regret aversion message framing in the FSB’s First Voice newsletter

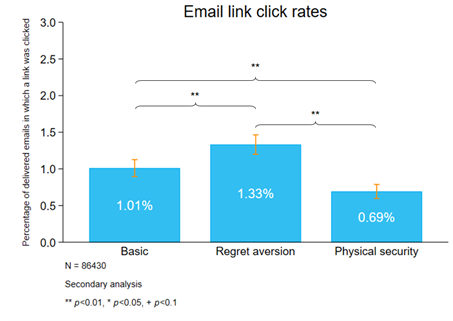

Disappointingly, very few businesses (<1%) signed up for a free website security scan. We found no significant differences in sign-up rates between our three messaging arms, however we did find variation in the number of businesses that clicked through to learn more. Business owners who received the regret aversion messaging were 32% more likely to click through to learn about the website scan than those receiving the basic security messaging (1.33% vs. 1.01%) and nearly twice as likely as those receiving the physical security messaging (1.33% vs. 0.69%). See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Regret aversion messaging prompting businesses to consider the potential consequences of an attack was most effective at encouraging businesses to engage with a website scan.

Our qualitative research suggests that one reason that our messaging may have been unappealing in general, and that the regret aversion messaging may have outperformed the other message frames, is that small businesses do not perceive cybercrime to be a threat. Asking businesses to imagine what might happen if they were attacked may have made the consequences feel more ‘real’ (changing businesses’ calculation of the risk) compared to physical metaphors, which assume that businesses already think they are at risk. Additionally, unlike the other messages, which narrowly refer to cybersecurity ‘hygiene’, the regret aversion message asks the recipient to think more generally about the knock-on effects of a website attack. This could prompt recipients to consider a variety of possible consequences (e.g. business continuity, damaged reputation, etc.), which may have made a website security check seem more critical.

We only collected a small amount of information on the barriers businesses faced to signing up for a free scan; conducting in-depth qualitative research with businesses both prior to and following any future trial would help to better interpret the findings. However, a recent study suggests that an ‘opt-out’ website security service may be an effective approach. In the study, websites were automatically (i.e. without website owner consent) scanned for a data protection misconfiguration. Researchers then wrote to website owners to inform them of the misconfiguration, if present. Results suggest that website owners found the (unsolicited) notifications useful — 34% of website owners sent a message of thanks (and even gifts!) to the researchers.

Trial 2: Encouraging businesses to patch vulnerabilities in their websites

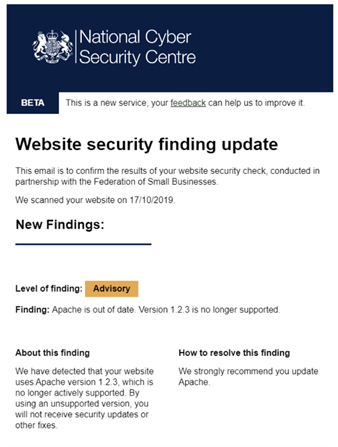

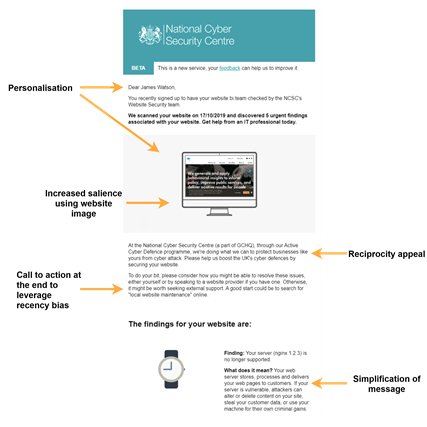

In the second stage of the study, we wanted to understand whether behavioural vulnerability alerts (Fig. 3) could encourage more businesses to patch vulnerabilities in their websites, compared to existing NCSC alerts (Fig. 4). Unfortunately, due to the small number of businesses who signed up for a free scan and had vulnerabilities in their website (115 businesses), we weren’t able to draw statistically robust conclusions from the results.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the existing NCSC alerts

Figure 4. Screenshot of the behavioural vulnerability alerts

In the pilot, we found some evidence that the NCSC alerts outperformed the behavioural alerts and that roughly half of the businesses receiving either alert took action and patched at least one vulnerability. With the sample size we had in this study, there’s a limit to the conclusions we can draw. However, these findings signal that feedback on vulnerabilities and a call to action, regardless of framing, may be powerful tools for encouraging patching behaviour. This aligns with the recent study mentioned above, which found that 56.6% of website owners addressed privacy issues after being notified, compared to just 9.2% of businesses in a control group.

Taken together, our findings suggest that a public alert service notifying businesses about their website vulnerabilities could help improve cybersecurity, and regret aversion messaging could increase engagement with such a service. Further research could expand on this work by robustly investigating what kind of notifications are most likely to prompt action. If you’d like to learn more about the study or our recommendations for further research, please get in touch!