“I know it like the back of my hand” is a phrase tossed around often. It conveys that a subject or route is known intimately and with great confidence. It is the verbal yardstick we use in everyday speech to indicate that we are absolutely sure about something.

But how well do any of us actually know the back of our own hands? And by implication, what does this tell us about other things we think we know?

BIT ran a quick internal experiment to get to the bottom of this (in)famous idiom. Turns out it reveals more about knowledge than one might think …

Testing our own staff

If we told you we were going to test your ability to recognise the back of your hands, you’d suddenly start looking at them more closely (maybe you just did). So when we decided to run a rapid experiment with our own colleagues, we didn’t want to give them the unfair advantage of “revising”.

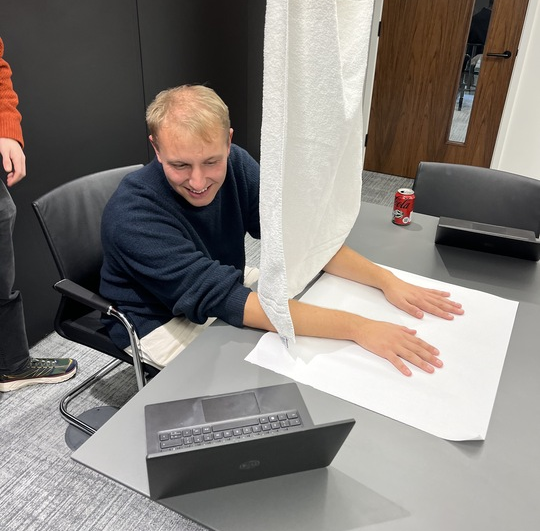

Our plan was to photograph staff members’ hands and then ask them to pick their own hand from a line-up. We needed to somehow get a picture of each participant’s hands, making sure there weren’t any obvious defining features they could use to identify their own hands (meaning nail polish, jewellery, and watches were all out), and we had to do it without tipping off other participants as to the focus of the experiment. We figured we had to do it all in one go, and ask participants to keep a secret afterwards.

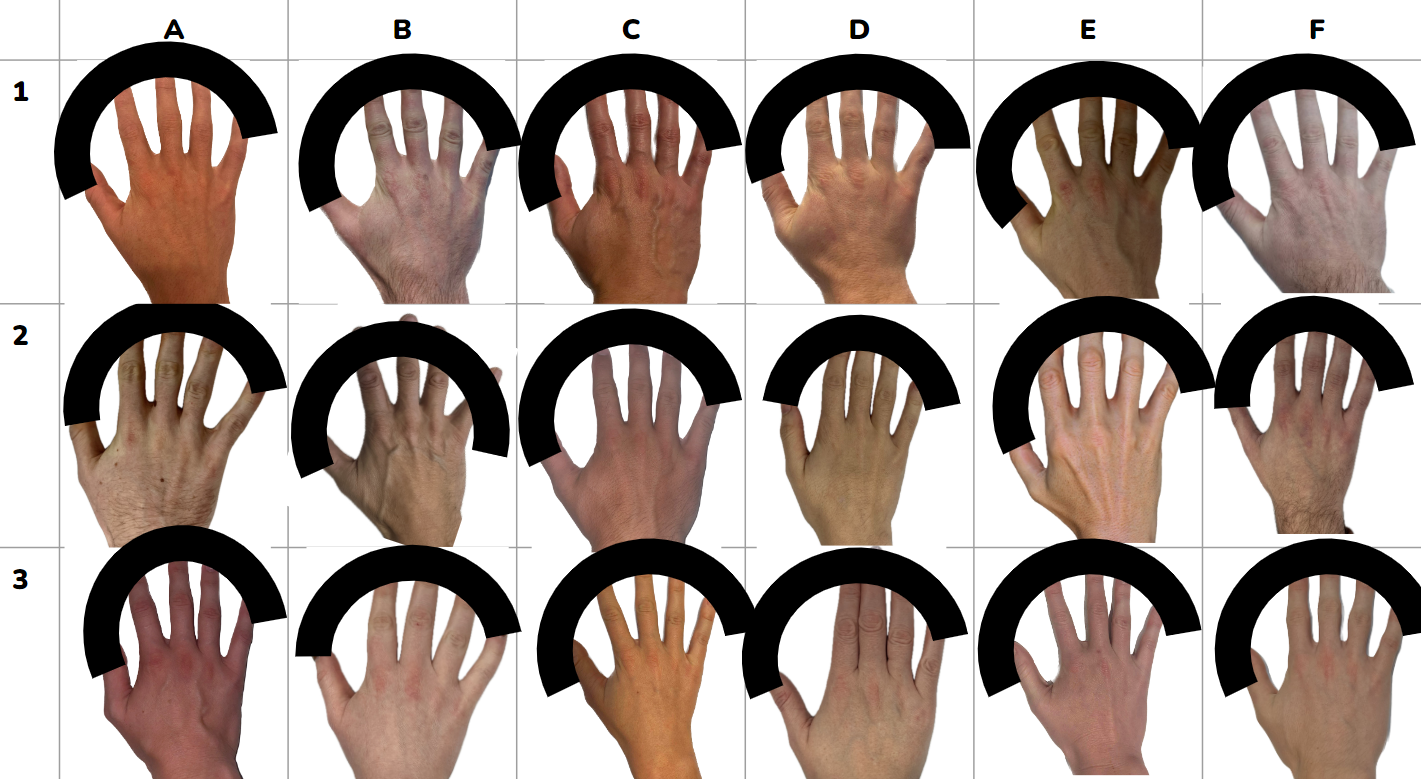

Members of the BIT & Nesta London offices were asked, one at a time, to come to a meeting room to participate in a brief task. Upon entering the room, participants were immediately asked to sit down and put both hands behind a screen. We removed rings or watches/jewellery, and took a photo of their right hand, palm down, which was immediately uploaded to a grid of similar hands (i.e. same gender and skin colour), with the nails covered up.

Before we showed the participant the grid of hands, we asked them: “Out of 100, how confident are you that you can identify your own hand?”. We asked them the same question once they had seen the grid too, giving them a chance to change their confidence rating.

In the end, 43 people took part – 19 men and 24 women.

What we found:

Only about half of participants could identify their own hand – 22 correct guesses to 21 incorrect guesses (51%). This is significantly more correct guesses than could be random chance from a grid of 18 options (5.6%), but still a long way from perfect knowledge (100%).

Participants were overconfident. Before guessing, participants’ average confidence was 71%. Once they were faced with the grid, some doubt kicked-in, but not enough: participants were still 64% confident on average, significantly higher than their 51% success rate.

Women know their hands better, but that didn’t dampen men’s confidence. Almost 2 in 3 women correctly guessed their hand, compared to just over 1 in 3 men. But, if anything, men were more confident. After seeing the grid, women were 61% confident they could identify their hand – slightly less than their 63% success rate. But men were still 67% confident – far outstripping their actual success rate of 37%!

So what?

It turns out, the back of our own hand is much harder to identify than the phrase suggests.

Of course, this was a small experiment, tested in just a few hours over a week, with a pretty unrepresentative sample (one that we might expect, for obvious professional reasons, to be better-calibrated on confidence than most!) But the results do stack up with what we see elsewhere.

Overconfidence is one of a core set of biases in behavioural science and refers to the human tendency to overestimate one’s own abilities, knowledge, or control over situations. It is sometimes known as the “illusion of knowledge”. It can lead us to believe we are more competent, talented, or knowledgeable than we actually are, often leading to decision-making errors. This can manifest in various ways, such as overestimation (overrating one’s actual performance), overplacement (believing one is better compared to others than one actually is), and overprecision (being too sure about the accuracy of one’s beliefs or predictions).

Overconfidence (or miscalibration) has real risks. The bias has been studied in a range of contexts, from driving, to diagnostics, to finance. For example, in a 1981 study, 93% of American drivers regarded themselves as more skilful and less risky than the average driver – beliefs that may actually raise the risk of dangerous driving behaviours. Such overconfidence tends to worsen the more senior we are (BIT found a similar effect in UK drivers, and especially in middle-age drivers). Similarly, physicians often underestimate the likelihood of diagnostic errors due to overconfidence – a 2001 study found that clinicians who were “completely certain” of the diagnosis antemortem were wrong 40% of the time. This overconfidence is well summed up by physician Atul Gawande in his 2001 piece for the New Yorker: “When someone dies, we already know why. We don’t need an autopsy to find out. Or so I thought.”

A closely linked phenomenon is the “illusion of explanatory depth”, which explains our overconfidence on processes we think we are familiar with (with more and less terrifying results). In one famous example, participants were confident they understood how familiar devices worked (including a zipper, piano key, and flushing toilet). That confidence dropped significantly once they were asked to actually explain it. More troublingly, in a separate study, participants who were shown a four minute silent video of two commercial pilots landing a plane in a mountainous area were significantly more confident in their ability to land the plane than those who did not watch the video, despite the video having no impact on their actual skills. Work in this area suggests that the internet may be adding to human overconfidence by building the impression that many things and skills are knowable – “I’ve seen it online, so I’m sure I can do it” (so began a million DIY disasters).

Speaking of DIY disasters, we are also not the first to find that overconfidence is more pronounced in men, with plenty of amusing findings. For example, one in five men think they could beat a chimpanzee (22%) or king cobra (23%) in a fight, while only 8-12% of women think so. But this gender disparity, too, has real-world consequences: for example, men in finance have been shown to trade more excessively than women due to overconfidence, resulting in reduced returns for men compared to women. And the plane landing study above? Surprise surprise, men were significantly more confident they could land a plane “as well as any trained pilot” than women.

“I know it like the back of my hand” is more than just a casual idiom; it’s an expression that offers insight into human cognition and confidence. We often take for granted the most familiar things in our lives, assuming knowledge or awareness that, upon closer inspection, may not be as detailed as we thought. Our brains are brilliant at covering the cracks of what we do and don’t know.

The next time you go to say “I know it like…”, think again. Maybe you don’t know as much as you’re claiming after all?

At BIT we’re interested in how humans think, and what that means for behaviour. Find out more about our work and services.