Last week the UK Government quietly published guidance for Civil Servants on using generative AI in government organisations. Among the promising potential applications listed is enabling citizens to find and interpret information about government services. Alongside this, the Government Digital Service (GDS) published results from user testing of a Gov.uk chatbot to do exactly this. They found that people liked the experience but that some technical challenges remain to ensure accurate answers.

At BIT, we’re similarly excited about AI’s potential to improve how citizens interact with public services – from providing tailored advice, to streamlining application processes.

But do people actually want AI in public services? We might happily use a chatbot to find out about shipping on our Amazon delivery but would we like to take health advice from an NHS chatbot? Would we trust the information? And will people even use these tools in the first place?

To find out, we ran an online experiment in partnership with Nesta to see whether and how people engaged with AI-powered chatbots on government websites.

What we did

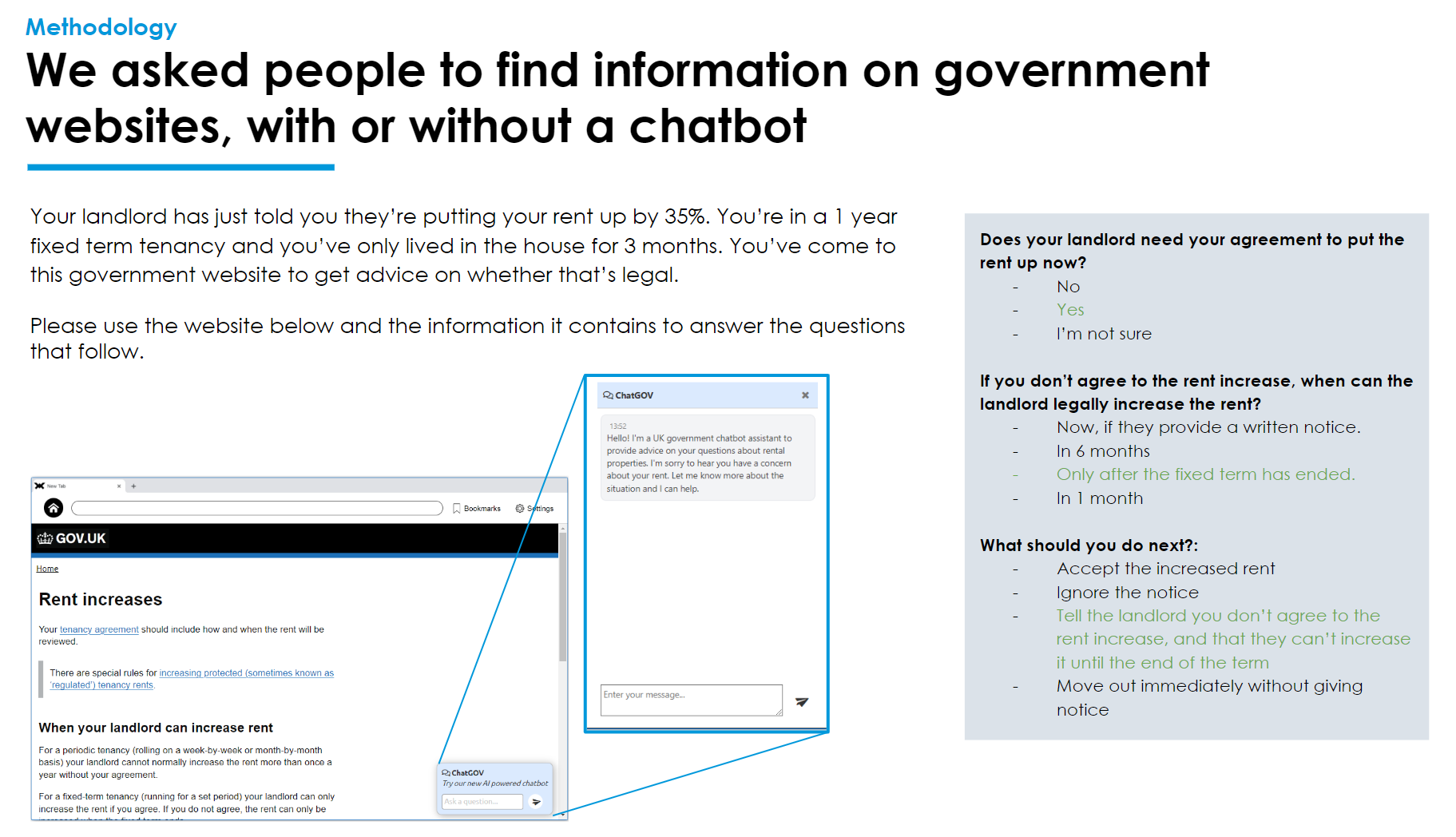

We asked just over 5000 adults in the UK to use government webpages to answer questions that involved two very different, but common, scenarios – solving a rent dispute and identifying constipation in a child.

Our control group saw only the standard government website (on gov.uk or nhs.uk).

In each of our four treatment groups, participants had access to a chatbot on the website, which varied in appearance, style and tone:

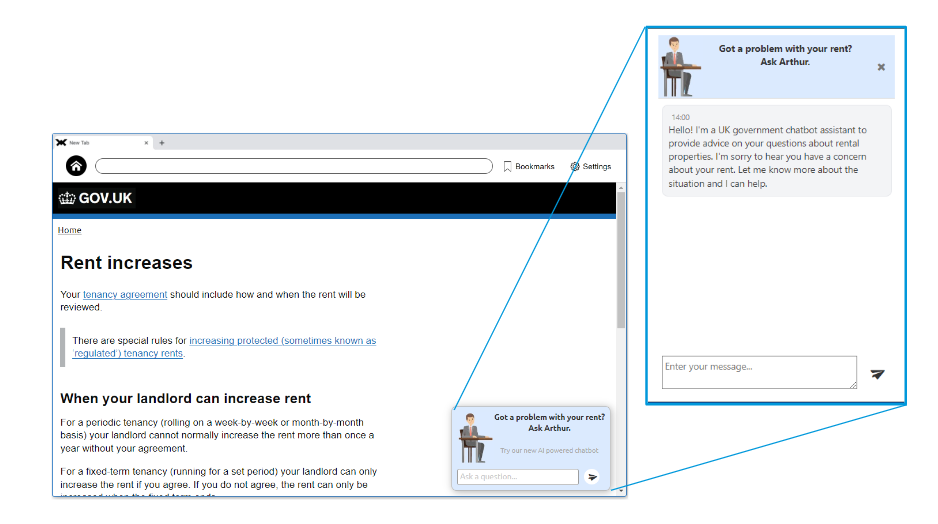

1: Basic bot. A bot in the bottom-right corner of the webpage, similar to how most chatbots currently appear. Test out the bot for yourself here.

2: Cartoon bot. Similar to the basic bot, but with a cartoon character and a prompt to “Ask Arthur”. This helped us understand whether personalising the bot increased trust and/or engagement. Test out the bot here.

3: Whole page bot. A bot that took up the whole top of the webpage (users could scroll down to get to the main government website). This aimed to maximise engagement. Test out the bot here.

4: Whole page ‘transparent’ bot. The same format as the whole page bot, but the first message from the bot emphasised how the bot was programmed and the limitations of AI-powered advice. This helped us understand whether similar disclosures would impact trust. Test out the bot here.

The chatbots were powered by OpenAI’s language model, but were prompted to respond based on the relevant government webpage.

All participants were asked the same questions to test their comprehension of the information provided. After they completed the tasks, we also asked participants general questions, including about trust in AI and its uses – both broadly and in government.

Example task, user interface and follow-up questions.

What we discovered

A majority of people think the government should use AI to help citizens. Support increases further when people are actually exposed to government AI tools.

In the control group who didn’t have access to any AI chatbots, 63% support using AI to help citizens find information and solve problems. Among those that had access to the AI chat – whether or not they used it – this increased to 75% on average.

This is really interesting, it indicates that exposure to AI increases acceptance. One could easily imagine the opposite finding – that, for example, people are comfortable using an AI customer service chatbot to help with online shopping, but don’t like the idea of the same technology in public services.

We also found that trust in AI generally was higher (63% vs 56%) among those with access to a chatbot, regardless of whether they actually used it.

What might explain this? Those with the AI chatbot reported finding the task easier. Therefore, it may simply be that people feel AI support will make their life easier and so are more accepting of it. It may also be that people generally trust government websites and so seeing an AI tool in that context gives validity and boosts their trust of the technology. In the GDS research people also highly trusted the AI answers despite warnings about possible inaccuracies.

This underlines the importance of building accurate and well designed AI tools. The problem is not that people ‘don’t trust AI’. It’s that they trust the tool and put in less cognitive effort, making them susceptible to – as one study dubbed it – ‘falling asleep at the wheel’.

But did the AI chatbot actually help people complete the task? This is where the results become nuanced.

A minority of people engaged with the bot at all – even on the whole page chatbot that was hard to ignore. We saw average engagement of 40% across all four arms, with a higher (but still reasonably low) rate of 50% for the more prominent whole-screen bots.

As tools like ChatGPT become more ubiquitous, interest in using embedded chatbots may increase. For now, it appears that people prefer to engage with web content directly, at least for simple tasks.

The groups who had access to the bot were slightly less accurate than the control group and took longer. This suggests that integrating the chatbot on these websites didn’t help people find information they were looking for. To understand this, we first reviewed the chatbot conversations to see if the bot was providing inaccurate information. This wasn’t the case.

One interpretation is that the chatbot may have been more of a distraction than an assistant on what was a pretty simple task. After all, participants just had to pick out some information on a short page of text.

In that context, the chatbot may have distracted them from the task at hand meaning they were less accurate and took longer. As an analogy, it’s like we gave people a very simple maths test but provided a fancy scientific calculator to help them. They didn’t need it, and it became a distraction on what was otherwise a clearly written page of information.

If we’d set a more complex task like interpreting the tax code, navigating a database of information, or understanding their eligibility for childcare, an AI chatbot might have improved performance.

That’s why we’re excited to do more research on how and where AI can really help citizens. This study shows that many are willing to use chatbots, and accepting of them. The question is now what tasks and context can this technology have the greatest impact.

We’re looking forward to doing more work on this topic in 2024. Please don’t hesitate to reach out to us if you’d like to be part of that.

Contact: Edward.Flahavan@bi.team or Info@bi.team.