As more residents and businesses fail to pay their sewer bills, cities across the United States have had to resort to turning off water services to prompt them to pay.

In some cities, sewer charges are included on the water bill and collected by the utility company. This makes it easy for cities to collect what they’re owed. But in other cities, utility companies have stopped billing for sewer charges and left it to the cities to collect the charges themselves.

This system change has led to large volumes of unpaid sewer bills. Earlier this year, Chattanooga, Tennessee and Lexington, Kentucky had a combined $15 million in unpaid sewer bills, with thousands of people eligible to have their water shut off.

BIT recently completed two randomized controlled trials in Chattanooga and Lexington as part of our engagement with the What Works Cities initiative. Our low cost interventions more than doubled payments from delinquent accounts across both projects, helping many people avoid having their water shut off.

Chattanooga

In Chattanooga, we helped the city’s Treasury Division test the effectiveness of enclosing a courtesy letter along with the bill.

Accounts eligible to have their water shut off were randomly assigned to one of two groups. A control group received the usual bill, while a treatment group received a courtesy letter enclosed with their bill.

The letter included language we have used in the past. It informed account-holders that while the city of Chattanooga had previously treated their failure to pay as an oversight, it would now consider their lack of payment a deliberate choice, and that they would be at risk of having their water shut off. This “deliberate choice” language, combined with the threat of having one’s water shut off, conveyed that the city took non-payment seriously.

The letter also included a red “Pay Now” stamp used in our previous work in Louisville, Kentucky and New South Wales that clearly communicated what action was required.

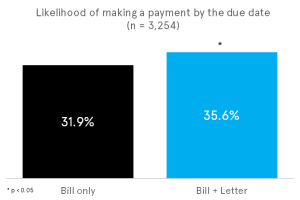

Nineteen days after the bills and letters were sent, we measured changes in customers’ account balances to gauge whether the letters increased payments.

We found that the added courtesy letter significantly increased the likelihood that an account made a payment by 3.7 percentage points.

If the letter had been sent to all accounts that fit our eligibility criteria, we estimate that the letters would have brought forward more than $117,000 in net revenue in one monthly billing cycle alone, after accounting for the cost of printing.

Lexington

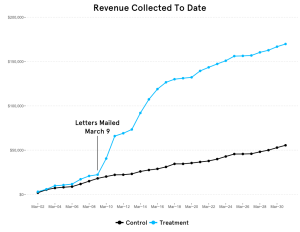

Building on our success in Chattanooga, we wanted to take our intervention one step further in Lexington.

Just like in Chattanooga, we randomly assigned a sample of customers with overdue sewer bills into two groups. The only difference between the two groups was that the treatment group received a courtesy letter. Again, the letter included the “Pay Now” stamp and the statement about their lack of response being treated as a deliberate choice.

But this time, we added a twist.

One of the biggest challenges faced by collection services is getting customers to open their mail. The most persuasive and behaviorally informed letter won’t make a bit of difference if it’s never opened. So, on the outside of each envelope, we added a handwritten note addressing the customer: “John, you really need to read this.”

Taking the time to handwrite a note on each envelope might seem like a technological step backwards, but a personal touch can make a difference by reminding the reader that there is an actual person on the other end of the letter. One study found that when a handwritten post-it note was applied to a survey, response rates more than doubled.

For this trial, it took less than two hours for five people to write messages on the outside of about 1,500 envelopes.

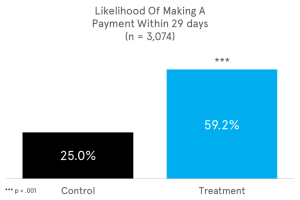

The results were impressive: the courtesy letter increased the likelihood of a customer making a payment by 34.2 percentage points.

After accounting for the costs of printing and mailing the letters, we estimated that the letters increased net revenue by over $112,000 in the trial period alone.

Had our letter been sent to the entire sample, we estimate that Lexington would have collected more than $225,000 in net revenue that month.

The long term effect on revenue brought forward may be even larger: the numbers reported represent actual payments made and do not include expected payments from customers on payment plans.

For cities, one lesson to take away from these results is that small changes can have a large effect, and they don’t have to cost a lot.