Another week, another UK Party conference. Once again we were there with Nesta colleagues, with panels on mission-led government, public health and obesity, as well as joining other events on topics ranging from supporting communities (with Demos and Local Trust) to inequality (with King’s Policy Institute).

Unlike the Prime Minister’s speech last week, Starmer arguably had less by way of specific policy detail. While he majored on the case for change, his speech did include ‘crunchy’ announcements to build 1.5million homes, ‘bulldoze’ through the UK’s increasingly slow-moving planning system, and a commitment to establish GB energy, Labour’s proposed vehicle for delivering a rebuilt energy system.

While deliberately not a policy heavy speech, it was the Leader of the Opposition’s fullest, and most personal, account of what he thinks ails Britain and how a Labour government might go about fixing it. He highlighted the many social, economic, and psychological factors behind the challenges facing the UK.

We will skip over the most overtly political elements of the speech (as we did for that of the Prime Minister), and instead draw out a few behavioural policy observations.

Before the speech even began, Starmer was accosted by a protester. It was an incident that understandably led media reports. With the killing of two Members of Parliament in recent years, the incident caused real shock – the protester gripped Starmer for a good seven seconds before security pulled him off. But as the shock wore off, and the hall reacted, the incident may have inadvertently served a purpose, by reinforcing how (non-violent) protests have gone from ‘normal’ at Labour party conferences (cf the slow clapping and heckling of 2021) to ‘abnormal’. Indeed Starmer leant into it as a symbol of a changed party.

There is an interesting behavioural angle here. Cialdini’s classic studies on social influence show how behaviour is generally contagious (we are drawn to behave like we see or think others around us are). But a lesser known detail of this work is that seeing a single, exceptional act of (bad) behaviour can actually make us even more likely to not engage in that behaviour. To take a real, albeit less severe example: we are much less likely to drop litter in an environment that is perfectly clean than where there is lots of litter already on the ground (a familiar example of social influence or ‘proof’ at work).

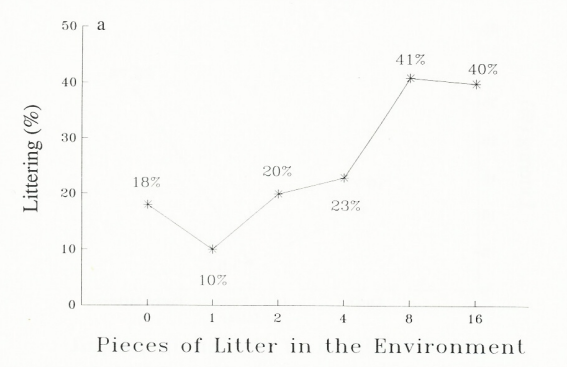

Percent of people who litter depending on the number of other pieces of similar litter on the ground already (Cialdini, 1991)

Curiously, however, we are even less likely to drop litter in an environment that is perfectly clean, except for a single piece of litter. It seems to prompt the thought ‘ugh! – how gross / that’s really not the way to behave / that’s not the kind of person I want to be’. It’s often said ‘if you can’t see it, you can’t be it’. But for exceptional behaviour, we sometimes go the other way: ‘I’ve seen it, I don’t like it, and don’t want to be it…’ In that sense, the protester potentially served to reinforce the commitment of others in the room – and perhaps online – to not behave in that way.

Age of insecurity

Starmer’s actual speech gave quite a bit of space to the social and psychological aspects of the challenges that the nation and its citizens currently face, particularly around poverty and insecurity.

Starmer dwelt on the lived experience of poverty – such as through the eyes of a struggling single mother. He drew out how people living in poverty flipped to ‘survival’ mode – a sense of the future disappearing beneath a gruelling focus on present and urgent needs. This account has strong echoes of behavioural work on ‘scarcity’ effects, as drawn out in the work of Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir – and indeed BIT work on ‘cognitive taxes’ linked to the experience of poverty (for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation).

People with money worries, or other pressing needs, show what is called mental ‘tunnelling’. Their mental resources become focused on addressing those pressing short-term needs, crowding out their attention and limiting their potential to focus on anything else. Poverty and disadvantage of course makes people more vulnerable to economic shocks (if their car breaks down, they can’t afford to fix it, and can’t get to work…) but also drives vulnerability on other fronts, around financial, educational and career decisions. Focusing on the psychological aspects of poverty has practical policy implications too. Allowing benefit claimants to receive their payments weekly rather than monthly (as in Scotland & NI) would be a relatively low-cost change that reduces the cognitive burden of budgeting and gives benefit claimants more stability. More regular payments have been shown to reduce credit card borrowing, so would align with Labour’s commitments on tighter regulation for buy-now-pay-later schemes, Attention was also drawn to the sense in which we are all living in ‘an age of insecurity’. A war in Europe. Spiking energy prices. Inflation. Climate change. And this week, renewed conflict in the Middle East. Traditionally it’s thought that when voters are prompted to think about external threats and insecurities, they shift to the right. So it’s interesting to see Labour taking on these issues – and the psychology underneath them – head on.

The behavioural literature has long noted how fear and anxiety changes our cognitive frame. When people are anxious, their senses and focus narrows as they get ready for ‘fight of flight’. In contrast, when we feel confident, happy and relaxed, our minds and cognitive style are more creative and open. It is one of the many reasons why smart employers want happy workers. The parallels to poverty-induced tunnelling are clear to see.

Social trust

Starmer also noted how, during covid, people pulled together. As we have documented in previous BIT blogs, this genuinely did seem to happen in the UK and some other countries. Social trust in the UK – trust in our fellow citizens – now stands at a 40 year high. Feeling that people around you are trustworthy and will help you out acts as a material and emotional buffer. Classic studies, such as Brown and Harris’s seminal work on depression (1978), showed how supportive social relationships acted as a powerful buffer against depression. As Holt-Lunstad’s meta analysis famously concluded, social isolation is as bad for your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

In the end, the speech makes a causal claim, inside a political plea, that we should ‘face down the age of insecurity together’ and in so doing ‘get our future back’. From a psychological point of view, this is probably true. Feeling supported and comforted by others is a good antidote to tunnelling and cognitive narrowing – literally bringing our future back into view. Indeed, it even appears to be built into our physiology: when we feel safe and cared for, our body switches resources from fight or flight to self repair (also thought to explain so-called ‘placebo’ effects).

And it may even be true on a macro-level. As popularised in ‘narrative economics’, sentiment has big impacts on economies, not least through business decisions on whether to invest or hold back, and household decisions whether to consume or hunker down. There has been much discussion about the Labour decision to play it safe on public finances (echoing pre-1997) as not to spook the markets or voters. Starmer’s speech restated that line, but also went further. He made the argument that if people and businesses pulled together the economy and society could lift. That is pretty much narrative economics in a nutshell. If everyone starts thinking things are going to get better, companies invest in new equipment and hiring, people shift from hunkering to spending, and kids and parents start thinking about the long-term instead of how to get through today.

Not for us to decide, of course. That’s for voters.