Many people think Britain is fading and a sense of gloom has overtaken the national mood. Nearly 70% of us think Britain is in decline and 40% think life will be worse for young people than it was for their parents.

You’d be forgiven then for assuming that we’ve all become less trusting and more cautious about our fellow citizens. Doom and gloom wouldn’t seem like a recipe for faith in our fellow Brits.

In fact, the UK is experiencing a quiet boom in what’s called ‘social trust’: the sense that we can trust our neighbours and the people around us. Our analysis of the latest release of the World Values Survey finds that 47% of us think that most people can be trusted. It is a measure that has improved markedly from 30% in 2005. The trend is also reflected in the British Social Attitudes survey, which – before it stopped tracking social trust – picked up a 10 percentage point increase between 2007 and 2017.

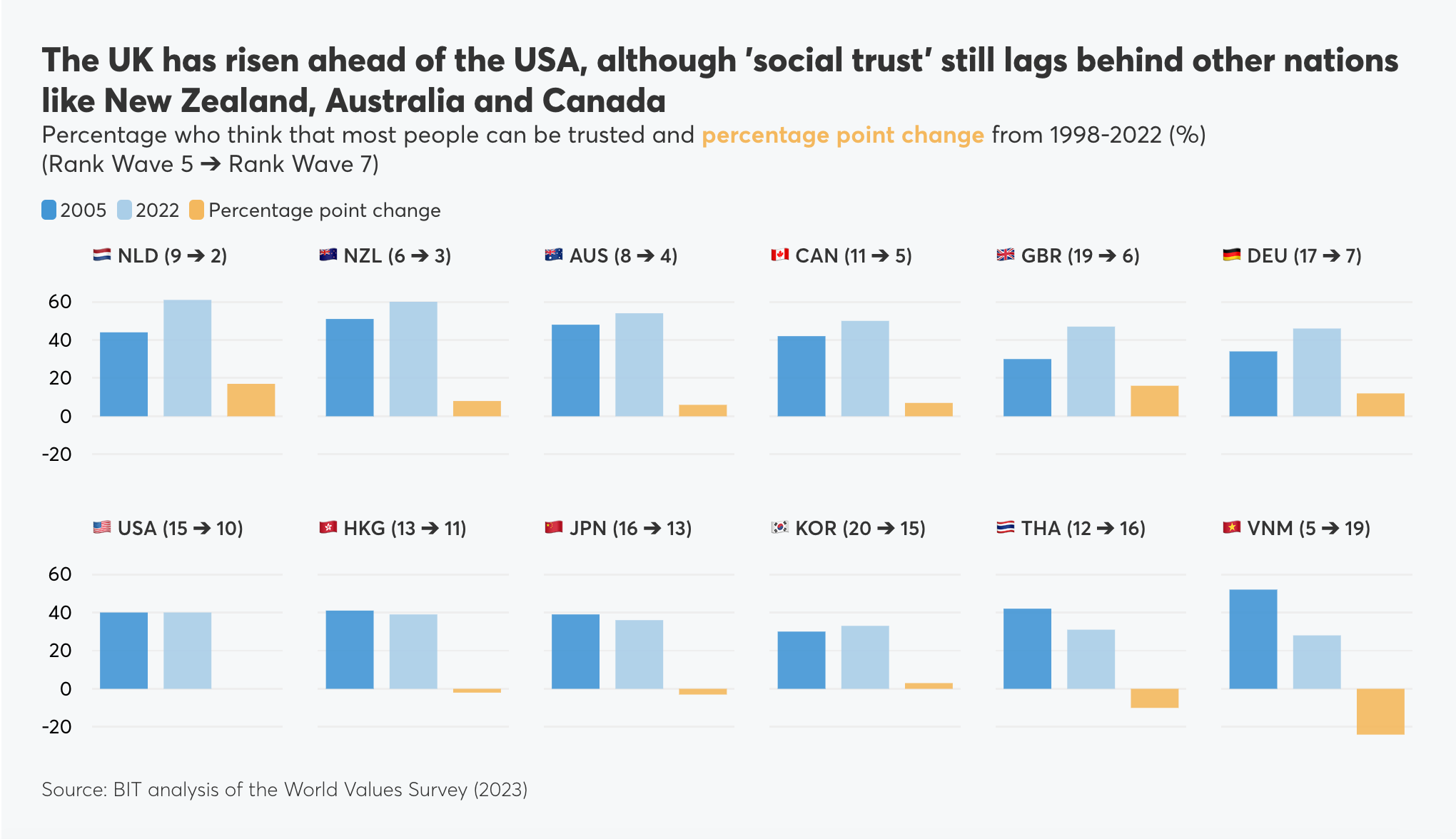

Last time we ran this analysis, Britain was a mid-table social trust country and heading in the wrong direction. The fall in social trust in the UK from the 80s to the noughties was more pronounced than in the USA – the subject of Robert Putnam’s famous ‘Bowling Alone’, which argued that civic life is collapsing. Now though, the UK has not just turned the trend line but stands out as one of the countries with the largest increase in social trust. The UK has leapfrogged the USA, although still lags behind other nations like New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

Trust is nice but does it matter? Yes. Social trust is like a social and economic policy wonder-drug. High social trust boosts economic growth through lowering ‘transaction costs’. You can do a deal on a handshake and feel confident you won’t be ripped off. It improves the flow of information because high trust generally leads to more openness. It also acts as a vaccine against nepotism – businesses employ the best person for the job rather than, say, the cousin of the hiring manager.

Social trust is also associated with lower crime, better educational attainment and even better performance of government. It’s easier to govern in a society where people help each other, follow laws and pay their taxes.

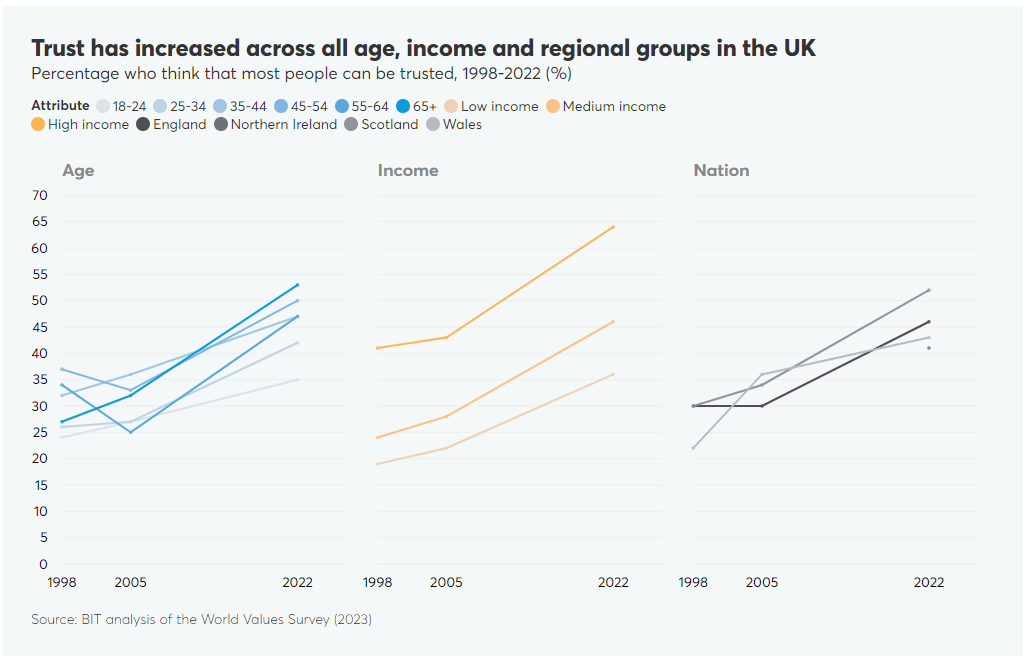

The steady increase in social trust also runs counter to other trends like intergenerational conflict and polarisation. Trust in the UK has risen across all age groups, all income levels and in all four nations of Britain. It’s risen steadily among groups that are sometimes pitted against each other, like baby boomers and younger people. The most striking increases are concentrated among the over 45s and people with higher incomes.

Trust is also good for our health and wellness. Across a number of longitudinal studies, people who report more social trust and better social networks live longer. This is thought to result from a combination of lower levels of chronic stress – being confident that you’re not literally or metaphorically about to be stabbed in the back – and because when you do get sick, someone comes and brings you chicken soup.

It’s especially vital in an emergency situation like a pandemic – when compliance, solidarity and a sense of the greater good takes on existential importance. In the early stages, Covid led to a wave of altruism in the form of volunteering, community building and exceptionally high compliance with the rules. Many of the interventions that were critical to containing the spread of infection rested heavily on trusting our fellow citizens. En masse, we washed our hands, stayed at home when sick, signed up to apps, wore masks, kept our distance and queued in the cold to get a vaccine.

Trust can also be seen in the data. Data on cross-national trust and measures of excess mortality due to Covid suggests that a one percentage point increase in the level of trust in a country was associated with a -4.13 decrease in excess deaths per 100,000 people. Of course, other factors are in play but this association does suggest that trusting our fellow citizens is every bit as important as trusting the government and the health system in a pandemic context.

Many lives were saved because most of us did the right thing most of the time for the benefit of others. Our analysis of the new WVS data suggests that this experience may have increased our collective sense of trust. Long-term analysis of social trust suggests it tends to be ‘sticky’, so it is quite possible that this shift will endure. Being able to trust your fellow citizens is good for health, wealth and happiness. The pandemic showed that it can be vital – the unseen glue between our collective efforts. There is a lesson here for our politics too. We face huge challenges, from health to climate to the economy. Mobilising our sense of shared endeavour – which is vital if we want to get to net zero, for instance – may be a richer seam than division and polarisation.

David Halpern is CEO of The Behavioural Insights Team. This piece is based on findings from the World Values Survey (WVS) in partnership with the Policy Institute at King’s College London.

To hear more from David about the changing landscape of social values in the post-Brexit UK, join us for a special event tomorrow in London.