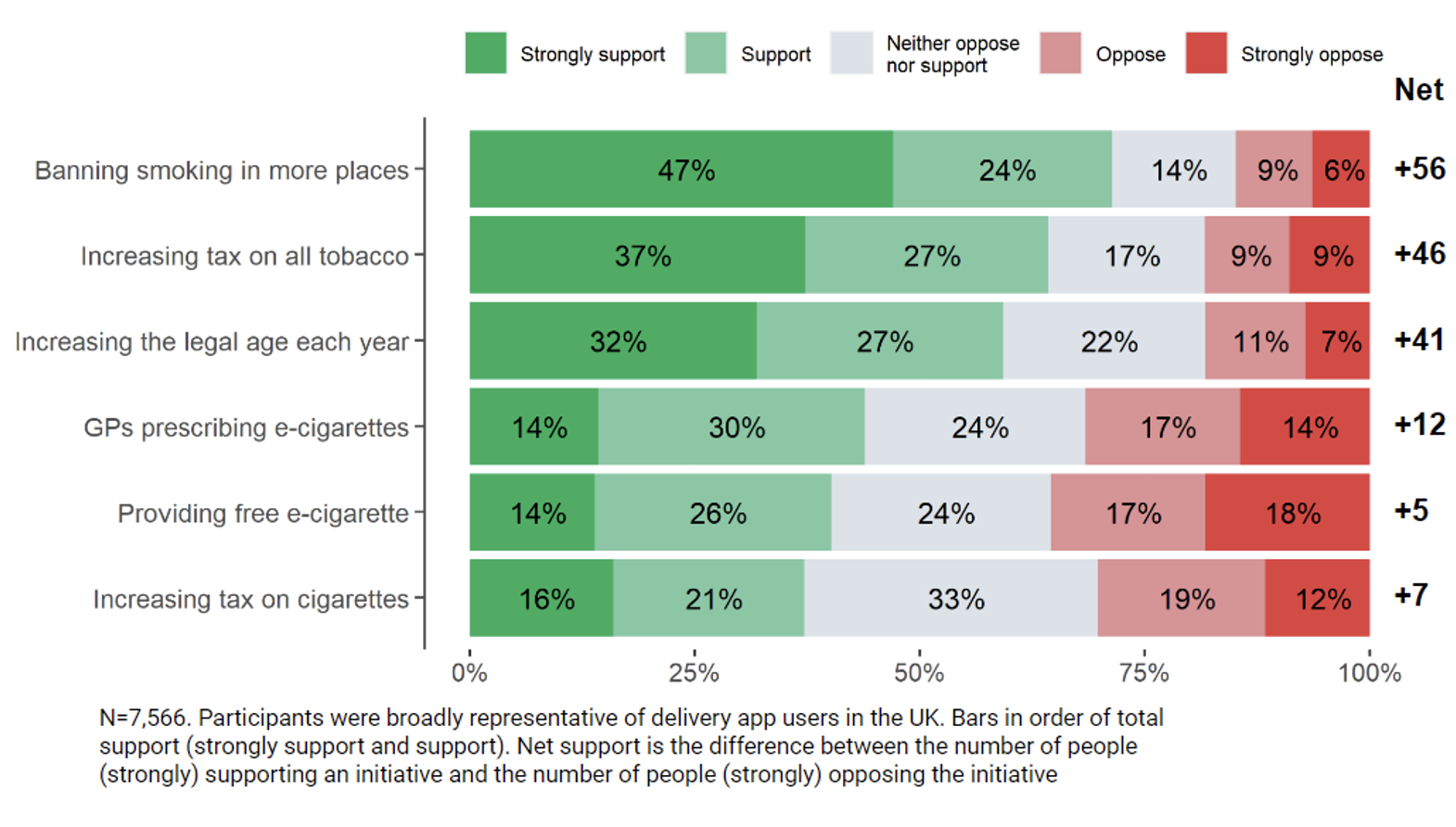

The PM can legitimately claim that this week’s announcement on smoking is a huge and important public intervention. Cigarettes are the only legal consumer product that, when used correctly, will kill the majority of users. Raising the smoking age on a regular basis, as New Zealand has done, was one of our recommendations to the Khan Review on making smoking obsolete, and is supported by the public, per a survey conducted by BIT last year:

Smoking kills around 8 million people a year, and 60-70k a year in the UK alone. It also kills unevenly: about half of the decade difference in life expectancy between rich and poor is explained by smoking. Most smokers picked up the habit as teenagers, and then spend a lifetime trying to quit.

Behavioural choices rarely work at the individual level alone. In some sense, smokers made a choice (albeit in previous generations without full knowledge about how horrifically toxic smoking is). That ‘choice’ will have been heavily shaped by advertising, peer pressure, and the normalisation of the habit (‘the choice architecture’). The smoker certainly didn’t choose all those pressures.

And habit is the right word. Smoking is a classic illustration of a ‘habit loop’: trigger-behaviour-reward (as popularised by Duhigg). The triggers can differ: having a drink, having a break, or simply just taking a pause from what you are doing. The behaviour is the cigarette (along with the associated hand movements, drag etc). And the reward is the nicotine and the buzz, or smoothing for long-time smokers. It’s very hard to break.

The gradual rise in the smoking age has other useful aspects that may help save our kids from this miserable habit. It will likely associate smoking with being old. As the market shrinks, cigarettes will also become less attractive for shops to sell or waste shelf space for, which will reinforce the shift – harder to find, harder to smoke.

This week’s announcement is made easier by the availability of behavioural substitutes, notably the vape. E-cigs provide an alternative that the trigger – in the habit loop – can be switched to. It’s really not that controversial in other areas of life that if an alternative is developed – in this case that is 95% safer – we often seek to phase out the more dangerous version. Think the phasing out of leaded petrol, or the use of coal to heat homes. This is a fairly classic harm reduction approach. Our rough estimate is that, since we worked in 2010-11 to make vapes available in the UK, they have already saved more than a million years of life.

But there is still clearly unfinished work to get the vape market in the right shape. It was definitely not the intent in the Cameron-era Government to get vapes into the hands of teens. Indeed, the strong expectation and intent was that regulation would be needed to keep vapes away from kids, and at the same time, that drug and other companies would bring forward medical-grade vapes through the MHRA licensing process so that medics could prescribe them. These prescribed e-cigs were expected to include restricted versions that would be able to administer higher, but reducing, nicotine doses that would help those with especially serious habits to quit. The fact that neither of these things happened was a significant failure in public health policy that needs urgent correction.

The PM’s other announcements also have interesting behavioural angles (what doesn’t?)

Transport decisions rest heavily on how we value time spent travelling. Historically, saving an hour on commuters’ journeys was given a substantial value in cost-benefit analyses, because it was equated with an hour of lost wages. Hence even an expensive HS2 system could be cost effective. But the world has changed. Many people can effectively use their laptops or phones for work while in transit. This shifts the priority away from speed towards capacity and the ability to work in transit.

Rather critically, that now implies having reliable broadband – and a reliable service – something notably absent on current London to Manchester trains (to pick an example!). Better wifi ought to cost a lot less than building entirely new train lines.

Interestingly, the same arguments may also come into play with autonomous vehicles. If you can sit in the back of a car and work (or even sleep), that totally changes the value and costs of journey times. Does it really matter if your journey takes an extra 20 minutes, if you were in the meeting anyway?

At the same time, easing the path to mobility is a powerful tool in combating poverty (cf Chetty, MtO). One of the features of the UK is the tapestry of disadvantage and opportunity that is woven across our cities and regions, such as the better employment prospects in the Midlands than adjacent North East. Enhancing connectivity, as shown by Henry Overman at the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth and others, can be a significant lever to drive firm and wage growth.

Even the PM’s proposed education changes have a striking behavioural angle. In general, educational systems that prompt or push kids to make ‘early selection’ choices perform worse than systems that delay those choices, so-called late-selection systems. Driving kids into academic or vocational pathways early on (cf technical vs grammar at age 11) is a bad idea – especially if there is a lack of ‘parity of esteem’, common curriculum or bridges – as is getting kids to choose only three subjects at age 16. This is because most of us don’t know at such an age what we will be doing a decade later, and because such early selection almost invariably leads to cementing of self-perception.

In fact, a core conclusion of the education review commissioned by Tony Blair in 2001 was that the UK should move to a ‘British Baccalaureate’. Of course, it never happened. The inertia in our systems, and particularly the strong influence of our universities over what gets taught in schools. The challenge for this PM, as for previous ones, will be whether he can make such a long-term change happen. That will depend almost certainly not just on him, but on whether other PM’s to come will hold the same line.

In that sense, what we really need is a political system that can be both bold, and consensus seeking. It’s why we are working with partners on the UK 2040 Options project. Now that is a really tough behavioural puzzle, but one worth taking on.