Concerns about an ‘epidemic’ of youth vaping seem to be making waves at the moment. We’ve seen recent headlines about a ‘spike’ in the number of children vaping, the Australian Government is planning to ban recreational use of e-cigarettes, and the UK Government has just announced £3 million towards a new ‘illicit vapes enforcement squad’ to help crack down on underage sales.

At the same time, there is good evidence that e-cigarettes are one of the most effective ways to help smokers quit, and so the UK government will also be providing free vaping starter packs to adult smokers and paving the way for vapes to be prescribed as medically-licensed products. We think this is a sensible move, but against the backdrop of the concerns about youth vaping, it’s understandable that many people may not know how to feel about e-cigarettes.

What are e-cigarettes?

Let’s start with the product itself. E-cigarettes use a battery to heat an ‘e-liquid’, which is typically made up of nicotine, flavourings and other substances such as vegetable glycerin. This produces an inhalable vapour (i.e. the small cloud you might observe when you see someone vaping in the street). Importantly, e-cigarettes do not burn tobacco and so they do not produce carbon monoxide and tar – two of the most dangerous elements of ordinary cigarettes.

However, e-cigarettes are not completely risk-free. Nicotine is addictive and, although we don’t really know enough about the long-term harms yet, there is some evidence that it may expose users to some harmful substances.

On the whole though, robust scientific studies have concluded that e-cigarettes pose only a small fraction of the risks of smoking. That’s why the UK Government wants smokers to use them to quit and, at the same time, prevent non-smokers (particularly children) from taking them up. Their advice is clear: “if you smoke, vaping is much safer; if you don’t smoke, don’t vape”.

How concerned should we be about young people vaping?

Let’s take a look at the data:

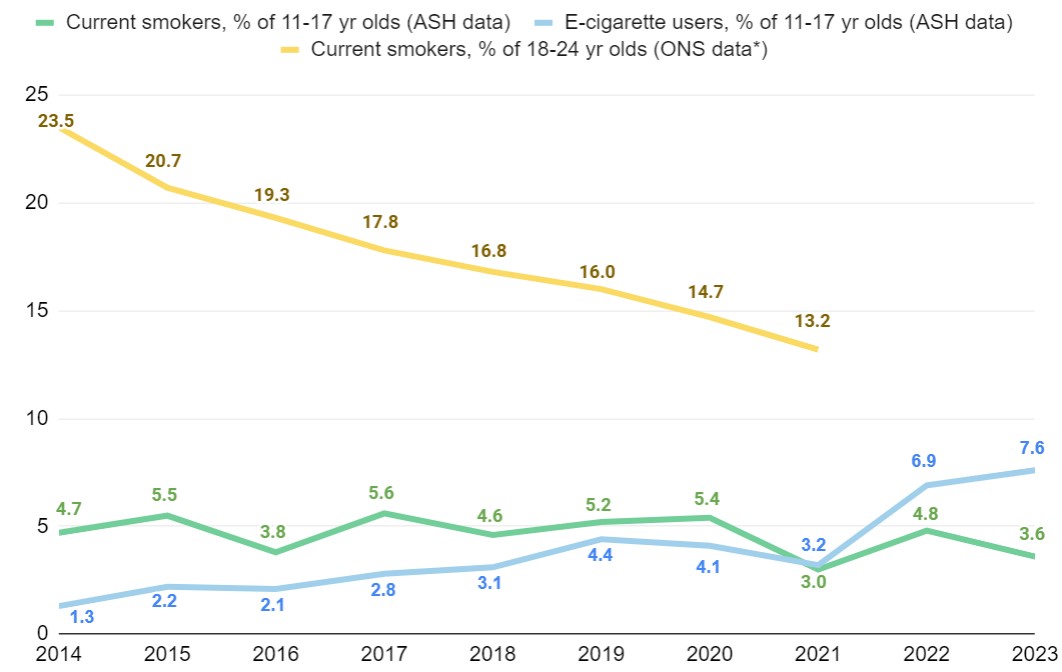

1: There has been a steep rise in the number of children who vape

According to Action on Smoking and Health’s annual Smokefree survey, in 2014 just over 1 in 100 young people aged 11-17 yrs used e-cigarettes at least occasionally. This year, that figure sits at just under 8 in 100. This represents a staggering increase over the past decade, and in the last two years in particular – even though it is illegal to sell e-cigarettes to anyone under the age of 18.

Sources: 1. Action on Smoking and Health (2023). Use of e-cigarettes (vapes) among young people in Great Britain. 2. Office for National Statistics (2022), Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2021.

Sources: 1. Action on Smoking and Health (2023). Use of e-cigarettes (vapes) among young people in Great Britain. 2. Office for National Statistics (2022), Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2021.

*ONS smoking data on 18-24 yr olds was only available up to 2021

2: Vapes don’t seem to be completely replacing cigarettes in the school yard

If young people were taking up vaping exclusively instead of smoking, we would expect to see a drop in the number of young smokers as vaping rates rise. This isn’t the case. The number of young people who smoke has remained relatively constant over the past decade, and now more young people vape than smoke.

Admittedly, the picture is complicated – the stats above don’t show unique vapers and smokers, so young people who smoke and vape count towards both the green and blue line. Additionally, it’s difficult to know what might have happened if e-cigarettes didn’t exist (e.g. perhaps e-cigarettes have prevented a rise in youth smoking?).

So, whilst e-cigarettes are helping some young smokers to quit smoking (~16% of current young vapers are former smokers), the data above also seems to suggest that at least some children who wouldn’t otherwise have smoked might be taking up vaping.

3: Vaping doesn’t seem to be driving a significant rise in smoking

If vaping was a substantial ‘gateway drug’ to cigarettes (as some have argued), then as youth vaping rates rise we would expect to see a corresponding rise in smoking rates. While many readers may know individual children who have taken up smoking after vaping, this story doesn’t seem to play out at the population level. Despite the rise in vaping rates over the last decade there has been no corresponding increase in smoking among 11-17 yr olds, and smoking rates have plummeted among 18-24 yr olds (i.e. the population that young vapers become).

Again, we don’t know what smoking rates would be like if e-cigarettes didn’t exist (might they have fallen even further among 18-24 yr olds?) so there is uncertainty to all of this. However, for the time being at least, the data gives us some confidence that we are not seeing a major boom in youth smoking as a result of rising e-cigarette use.

What should we make of this?

E-cigarettes aren’t entirely risk-free, so we perhaps have reason to be somewhat concerned about the rise in youth vaping that we’ve seen over the last few years. Even if they pose only a small fraction of the health risks of cigarettes, vapes are addictive and expensive, so it is right that the UK Government should consider whether to restrict the way they are being marketed at young people.

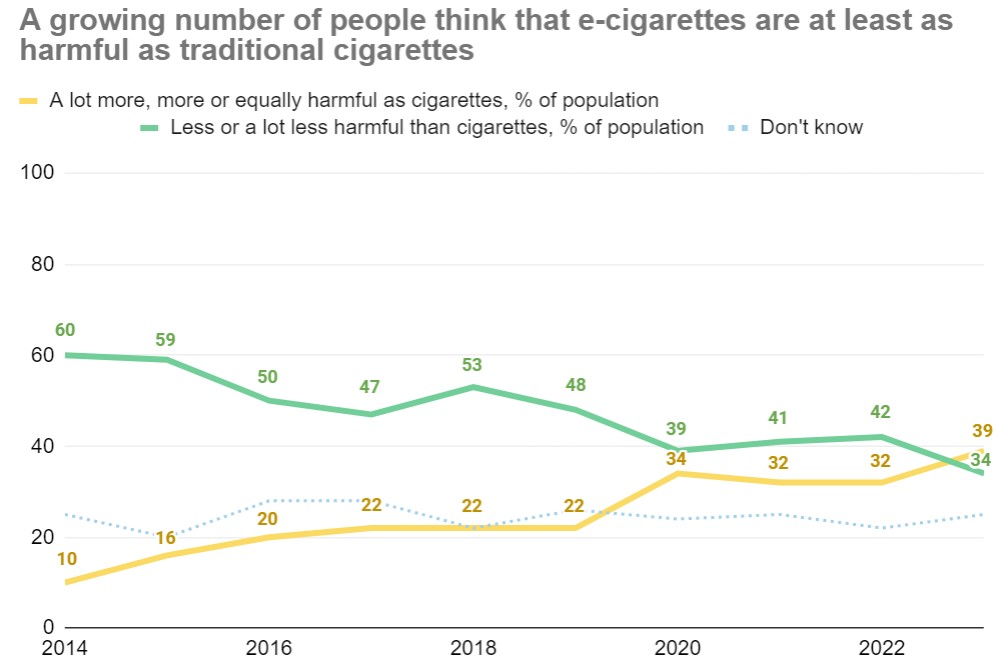

However, as we’ve highlighted previously, smoking is responsible for a huge amount of harm (around 75,000 deaths in England each year) and e-cigarettes are one of the best tools we have to help smokers quit. There is also a growing misconception that e-cigarettes are more harmful or as harmful as cigarettes, and fragile public support for smoking cessation efforts that involve e-cigarettes. We need to be careful that work to prevent youth vaping doesn’t undermine our efforts to encourage smokers to quit, either by making smokers think that e-cigarettes are more harmful than they are, or by turning the public against their use as a smoking cessation tool.

Source: Action on Smoking and Health (2023). Headline results ASH Smokefree GB adults and youth survey.

This doesn’t need to be an ‘either-or’ situation. With all that behavioural science has to say about risk communication, there must be effective ways to help smokers to quit using e-cigarettes whilst also preventing young people from taking them up, for example:

- Considering the way e-cigarette packaging is designed to minimise their appeal to young people while not putting off adult smokers – for example, researchers at King’s College London found that plain green packaging decreased the appeal of e-cigarettes to young people while marginally increasing their appeal among adults.

- Targeting e-cigarette communications at existing smokers via stop-smoking services or smoking cessation apps, and finding simple ways to explain the relative risks of smoking and vaping (such as this recent piece from Chris Whitty, the Chief Medical Officer for England).

- Helping GPs to feel confident advising patients about the use of e-cigarettes to quit smoking – a quarter of UK GPs are unsure if e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes, and many practitioners have low confidence in their ability to give advice.

We know more can be done to tackle the harms of both smoking and youth vaping, so if you’re interested in partnering with us to deal with this problem, please contact us (or email: Filippo.Bianchi@bi.team).