Sexual harassment on public transport is an all too common occurrence in Bangladesh and around the world, with the majority of women in many countries – and in some cases over 90 percent of respondents – having experienced sexual harassment in the past.

Many of us would like to think we’d do something to stop sexual harassment if it happened right in front of our eyes. Indeed when we surveyed over 3,000 commuters getting off public buses in Dhaka, 9 out of 10 respondents listed at least one helpful action they would take if they saw a woman being harassed on a bus.

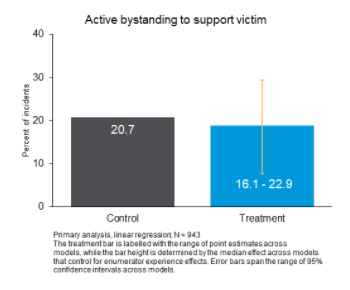

But when trained observers took bus rides in the nation’s capital, we found bystanders took action in only 1 out of every 5 cases of sexual harassment.

How could we close this intention-action gap? And how might we know if it worked? We partnered with BRAC, the world’s largest NGO, to see what we could learn by applying human-centred design and innovative measurement techniques to this challenging problem.

Active bystander programs show promise in countering the ‘bystander effect’

The study of bystander inaction dates back to at least the 1960s, when American researchers Bibb Latané and John Darley documented the “bystander effect”.

In a series of experiments, passive bystanders were shown to inhibit others from acting in apparent emergencies. In some cases, this seems to occur because of ambiguity over whether the situation really requires action; if no one else is responding we conclude that we also don’t need to respond.

Active bystander campaigns around the world, such as Stand Up and Not On My Bus, have aimed to encourage us all to be allies in stopping harassment by running awareness campaigns and training programs. A systematic review of 27 studies of bystander training programs aimed at adolescents and college students found beneficial effects on knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy and self-reported intervention behaviour.

A project led by our Sydney team showed that even light touch approaches can work to overcome bystander inaction. In collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, our colleagues sent a series of active bystanding emails to close to 30,000 staff and students at Victorian universities. We found that people who received the emails were 30% more likely to report having taken action in a situation where they observed sexual harassment than a control group who received no emails.

Testing a bystander nudge on public buses Dhaka

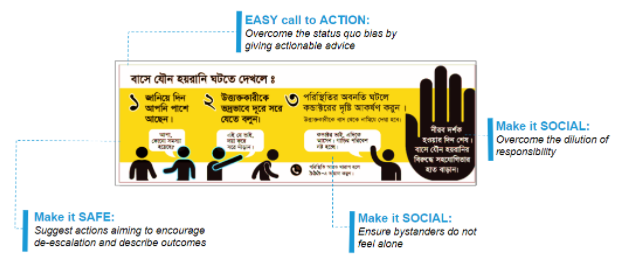

We worked with BRAC to test another light touch approach, this time targeting the millions of individuals who catch public buses every week in Dhaka. Given the importance of ‘making it timely’, we designed and installed bright yellow posters inside buses so that they’d be visible to all at the moments when harassment actually occurs.

Apart from attracting attention at the right time, the posters helped bystanders to speak up by visualising three simple and safe actions to take: i) engage the person being harassed to show support; ii) politely address the harasser and ask them to move away; and iii) alert the conductor if the situation escalates, so the harasser can be asked to leave the bus.

Going one step further than with previous work, we combined surveys of passengers with structured observations conducted by trained observers. Together with D2, a Dhaka-based research firm, we developed an app-based survey tool to measure not only changes in awareness, attitudes and willingness to act (as previous work had done) but also actual behaviour.

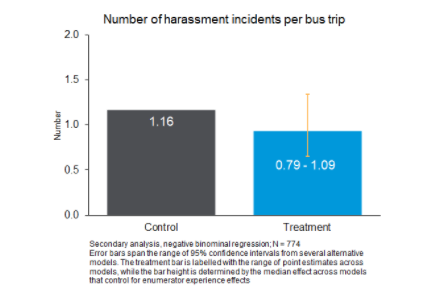

We uncovered sobering new insights about the prevalence of sexual harassment in this context. In the week before the posters went up, we observed harassment on 6 out of every 10 bus trips, with physical acts such as groping and “unnecessary touching” being most common. This amounted on average to one incident every two hours and forty-five minutes. Almost all victims were women, and close to 1 in 10 women reported experiencing harassment on the bus trip they had just taken. These numbers may even underestimate the risks women routinely face, given the challenges of observing crowded spaces and eliciting candid responses about harassment.

By comparing data collected in the week before the posters went up with data from the week immediately after, we obtain a picture of the impact of the posters. We did not find any evidence that the posters changed bystander behaviour significantly in the following week. This result isn’t conclusive enough for us to say for sure that the posters had no effect at all on bystander action, but may reflect additional barriers, such as uncertainty about what constitutes harassment, that the posters failed to overcome.

We did, however, observe other promising changes:

- Among both men and women, we found that measures of rape myth acceptance fell by over 10%.

- Men were more likely to report sexual harassment as a safety concern – possibly because the posters made the issue more salient – while the proportion of women reporting it as their biggest concern fell, from 10% to 6% – possibly because the posters provided assurance that harassment would not be tolerated.

And most promisingly of all, we observed a reduction in the number of harassment incidents per bus ride. Though the size of the change is uncertain and we cannot conclusively attribute all of it to the posters, it seems plausible that salient calls for bystanders to act could make potential perpetrators think twice.

If the threat of active bystanding really can deter individuals from harassing others in the first place, we have a huge opportunity to improve women’s lives. Have a read of our full report to see how more evidence could be generated to progress the ongoing fight against gender-based violence around the world, and get in touch if you’re interested in trying something similar in your part of the world!