This is the seventh blog in our Behavioural Government series, which explores how behavioural insights can be used to improve how government itself works.

Why might members of one group involved in making policy reject the arguments coming from another group, even if they are good ones?

This kind of “inter-group opposition” builds on a few other concepts we have explored before. For example, group reinforcement and the illusion of similarity strengthen a policy maker’s sense that their proposal and perspectives are right. If someone disagrees, this must be because they are incompetent, biased or malicious – and it is particularly easy to think this if they are seen as belonging to a different group. Even strong opposing arguments can be dismissed as a result, to the detriment of the ensuing policy.

Underpinning this problem is the way that we identify ourselves with “in group(s)” in contrast to “out group(s)”. We believe that the groups we identify with are better than other groups. That is the case even if a) there is strong evidence they are not, or b) they have only just been created, and we therefore have no prior attachment to them.

This strong identification means that, when groups have to co-operate, people are biased towards their in-group. In fact, evidence shows that when groups interact with each other they are less cooperative and more competitive than when individuals interact with each other.

For example, one study created a game where participants competed to win a prize by engaging in wasteful spending. Spending levels were much higher if groups were competing than if individuals were competing. And both were greater than a rational analysis would predict. In other words, this opposition between groups can lead to poor outcomes and greater risk taking.

Another cause of these group dynamics is the way we view our own opinions. People often think that they personally are unbiased, and that others will think the same way – if they get the facts.

If another party does not think the same way, then our preferred reaction is not to reassess our own opinions. Instead, we try to come up with ways of denigrating the opposition. This happens because we find it hard to maintain both a positive image of ourselves and a positive image of someone who disagrees with us.

The way that this denigration usually plays out in policy making is that we decide that those who think differently are biased, through ideology, self-interest, malice or stubbornness. While we have considered the issue carefully, they are just proceeding from dogma. This perception of bias makes conflict and division escalate further. As a result, both sides may reject ideas, compromise and dialogue that could lead to a better outcome for all.

One way conflict can escalate is through “false polarization”: we see the other group’s views as more extreme than they actually are. In our minds, we falsely make the group more distant and different from us.

This process happens most clearly between competing interest groups, where has been called the “devil shift”: seeing your opponents as more extreme and evil than they actually are.

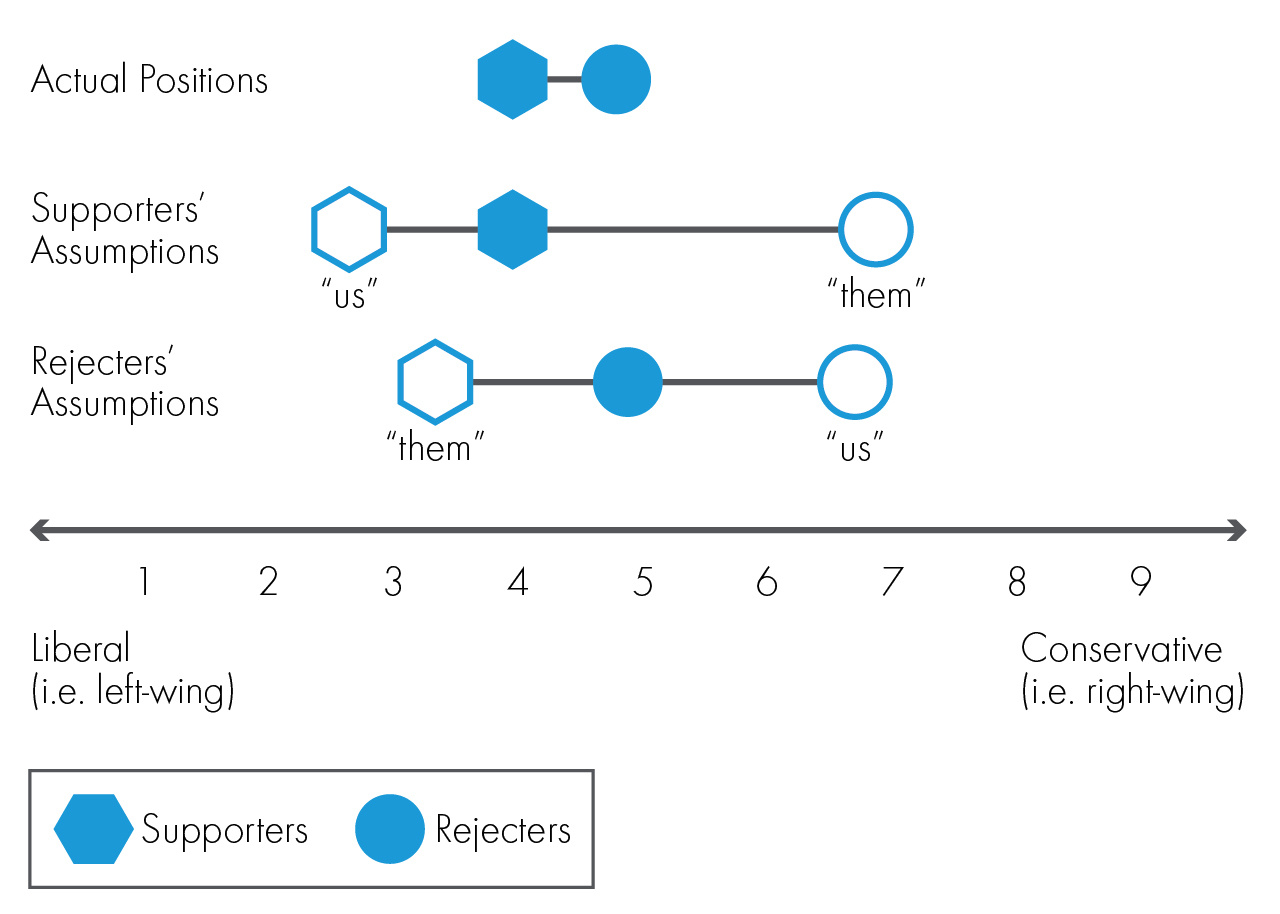

For example, one study asked people whether they would support an “affirmative action” programme to increase the diversity of a university’s student intake. The participants were asked to place themselves along a nine-point scale from liberal to conservative (i.e. left-wing to right-wing). They were also asked where they would place people who a) supported and b) opposed to the proposal along this political scale.

In reality, supporters and opposers did not differ much in their self-reported political views (see Figure). But their relative perceptions of themselves and the other group were more extreme. The supporters thought their own group were more left-wing they actually were, and their opponents much more right-wing; the reverse was true for the opponents of the policy.

Actual and perceived differences in political positions among supporters and opponents of affirmative action. Adapted from Sherman, Nelson & Ross (2003).

While these issues are most intense between competing policy pressure groups, they also occur within government itself. Governments are made up of various groups: departments, offices, committees, agencies, teams, ministerial alliances, professional communities, and so on. Culture and behaviours can vary greatly from institution to institution – as can the way that an issue is understood and framed. There are often few incentives to join up policy between departments, since they usually control their own budgets and line management, effectively creating competing power bases.

As a result, policy can emerge through an adversarial process where evidence is used to justify the position of a department (or similar group), rather than a collaborative exploration of potential options and approaches. That is why this inter-group opposition is an important focus of our upcoming Behavioural Government report, which will be released next month.