Alcohol consumption is a significant public health challenge globally, contributing to an estimated 3 million deaths every year; 5.3% of all deaths worldwide.

COVID-19 might have further increased the harms from alcohol consumption: Public Health Scotland published new statistics in March 2023 showing that the number of deaths occurring as a direct consequence of alcohol increased by ∼19% in England between 2019 and 2020, with a further ∼7% increase between 2020 and 2021.

Worryingly, 33% of these deaths occurred in the most deprived group. This suggests that alcohol consumption might contribute to widening the health inequities that already exist in England.

We surveyed 7,566 adults to understand what might motivate them to drink less alcohol

At BIT, we wanted to explore what might motivate people to reduce their alcohol intake after COVID-19. This could help us and other health organisations to design initiatives that better support people to reduce their alcohol consumption.

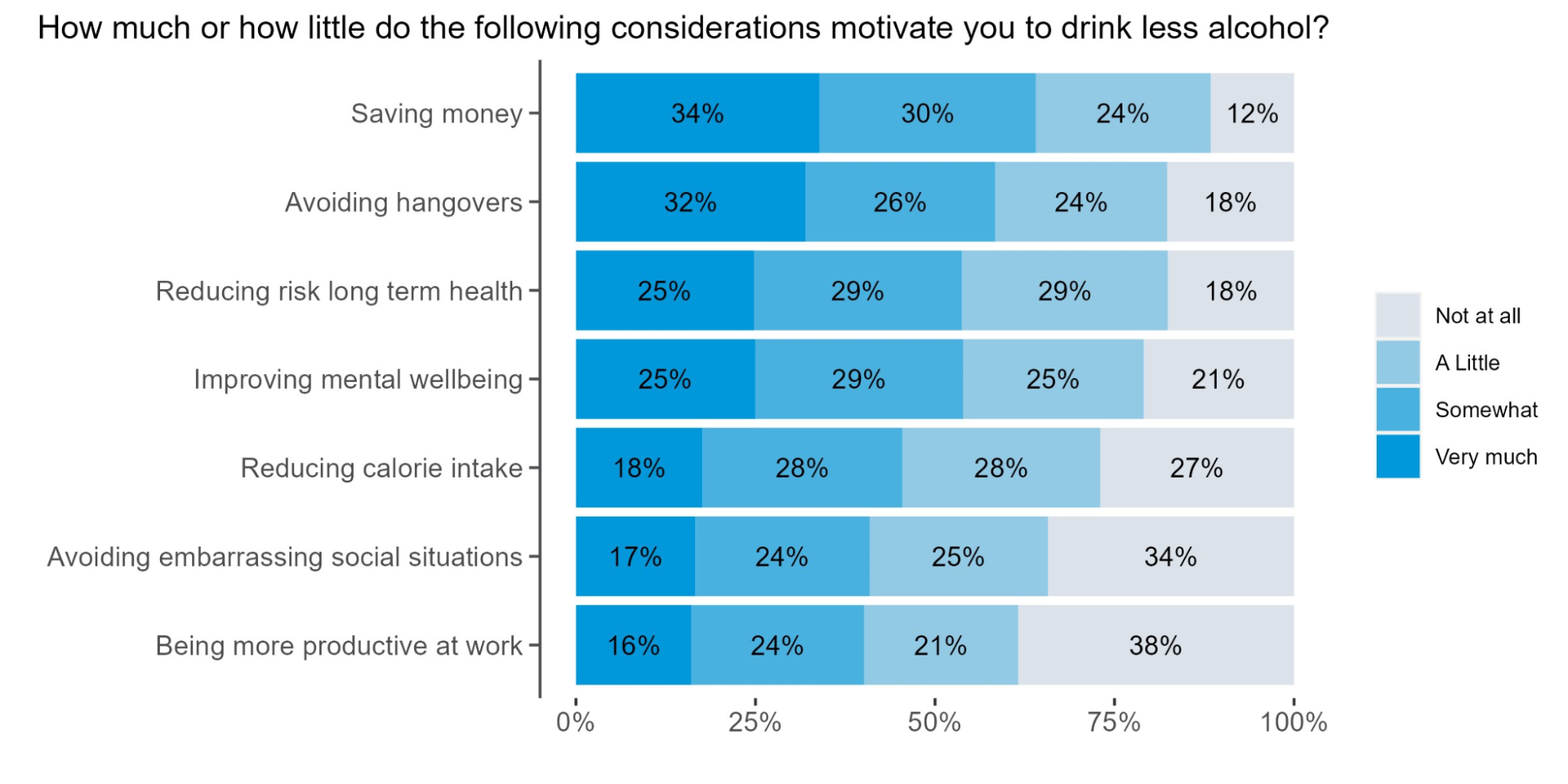

We asked 7,566 adults living in the UK to rate the extent to which seven factors motivate them to drink less alcohol. The seven factors we asked about were identified through a review of the scientific literature and included:

- Saving money

- Reducing my risk of long term health conditions, like cancer and liver disease

- Improving my mental wellbeing

- Avoiding hangovers

- Being more productive at work

- Reducing calorie intake

- Avoiding embarrassing social situations

Saving money and avoiding hangovers are the most common motivators for reducing alcohol consumption

All the potential motivators we asked about influenced a large proportion of respondents’ decisions to drink alcohol. Saving money and avoiding hangovers were rated the most important, with 64% and 58% of respondents, respectively, saying these factors ‘very much’ or ‘somewhat’ motivated them to drink less. Even the ‘least significant’ factor, being more productive at work, motivated 40% of respondents to drink less alcohol, indicating that all the factors that we asked about played a role in motivating respondents to drink less alcohol.

We also found a difference by income level: those earning more than £40,000 were significantly less motivated to drink less for money saving reasons than those earning less than £40,000.

So what might this mean for health organisations aiming to reduce harm from alcohol consumption?

1: Reducing affordability and highlighting saving potentials could motivate reductions in alcohol consumption.

Evidence consistently shows that affordability is a key determinant of alcohol consumption, and alcohol is now 72% more affordable than in 1987. Despite increasing affordability, drinking alcohol regularly remains costly. An average UK household spends £14.30 per week on alcohol. This adds up to £744 a year: 3% of the typical UK household budget and far more than we spend on fruit and vegetables (£649 each year on average).

One way that we can reduce excess alcohol consumption is by addressing its affordability through minimum unit pricing, where a minimum price is set per unit of alcohol sold. A minimum price of 50p per unit was introduced in Scotland in 2018 and in Wales in 2020, and has shown promising results. Since the policy’s introduction, alcohol sales in Scotland have fallen to their lowest levels in 25 years, and deaths attributable to alcohol consumption have fallen by 13%.

Heavy drinkers typically account for most of the national alcohol consumption and are particularly influenced by drinks’ affordability. Policies such as minimum unit pricing are therefore likely to work particularly well among these people who might benefit the most from cutting back. This is consistent with a scientific study, which found that a minimum price of 50p per unit of alcohol would reduce consumption in harmful drinkers around 200 times more than in low-risk drinkers.

Increasing alcohol duty is also likely to reduce excess consumption: research from the University of Sheffield found that increasing alcohol duty by 2% above inflation from 2020-2032 would save over 5,000 lives and prevent almost 170,000 hospital admissions. In addition, increasing alcohol duty would increase revenue: the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that alcohol duties could raise £13.1 billion in 2023/24, representing 1.2% of all tax receipts.

We can also encourage reductions in alcohol consumption by encouraging industry reformulation. Alcohol duties can be designed in a way that encourages industry to produce and promote drinks that contain lower volumes of alcohol, or even low- or no-alcohol alternatives. This would be similar to the mechanisms underlying the success of the Soft Drink Industry Levy, where the introduction of a tiered taxation system on sugary soft drinks was followed by significant reformulation from manufacturers, who reduced the sugar in many soft drinks to avoid the higher tier taxes.

2: Mandating calorie labels on alcohol drinks could encourage reduced alcohol consumption.

Our study found that 46% of respondents were ‘somewhat’ or ‘very much’ motivated to drink less alcohol in order to reduce their calorie intake. Yet alcoholic drinks are currently exempt from calorie labelling, meaning that most people are unaware of how many calories they are consuming when they drink alcohol. Making calorie labels compulsory on alcoholic drinks, as with food, would allow people to be aware of the calories that they are consuming through alcohol and, as a result, to make more informed choices about how much they choose to drink.

Many alcoholic drinks have a high calorie content: the NHS estimates that drinking 5 pints of lager each week adds up to 57,720 kcal in a year, and the Royal Society of Public Health estimates that calories from alcohol provides approximately 10% of calorie intake for adults who drink. Given the high calorie content of alcoholic drinks, and rising levels of overweight and obesity, confusion and lack of awareness around calories contained in alcoholic drinks is concerning.

Previous work by BIT and Nesta found that adding calorie labels in a simulated food delivery app can significantly reduce calories purchased by up to 8%. Public acceptability for the calorie labels was high, with 71-76% actively supporting the introduction of calorie labels.

3: Design digital interventions to specifically target the top motivators to cut down.

Many digital interventions such as Drinkaware’s app already use behavioural elements to help people set drinking goals and receive feedback. These features could be expanded to include personalised financial and health-based motivators, which emerged as important in our survey.

As financial considerations play a key role in motivating people to reduce the amount they drink, digital interventions could include features to allow people to track the amount of money they save by reducing their alcohol intake, such as in the ‘Try Dry’ app.

We also found that avoiding hangovers and improving mental wellbeing were also significant motivators to reduce alcohol consumption. Expanding digital interventions to allow people to record ‘hangover symptoms’ and ‘mood’ could allow people to track the influence of drinking on their physical and mental health and receive personalised feedback.

What is next?

People are motivated to reduce alcohol consumption by a range of factors: financial motivations were the most common, followed by desire to avoid hangovers and to improve mental wellbeing.

In this blog we provided three examples of how this research could help to inform policy: Price-based interventions, such as the introduction of minimum unit pricing are likely to have widespread beneficial impacts, particularly among the heaviest drinkers who are at the greatest risk of health harms. Mandating calorie labels on alcoholic drinks could also allow people to make more informed decisions about their energy intake from alcoholic drinks, and will enable those who want to drink less to reduce their calorie intake, as we found in our study. In addition, targeting individual-level interventions, such as digital interventions, to focus on specific motivators that emerged as important in our study is likely to result in greater success at reducing alcohol consumption at the individual level.

These interventions could form part of a wider portfolio of strategies that jointly target the personal, environmental, and social determinants of harmful alcohol consumption and might help to improve population health.

The Behavioural Insights Team is excited to collaborate with partner organisations to reduce harmful drinking and to discuss health policy. If you would like to work with us, please get in touch (or e-mail: filippo.bianchi@bi.team) and we would be delighted to arrange a meeting.