In the world of education, the PISA results are the World Cup, Olympics and Oscars all rolled into one. For a generation they have provided the benchmark study on how well our children are learning – and how well our educational systems are performing.

Education Ministers, and Governments, across the world will be celebrating – or looking for new jobs – depending on the results. This year’s results have been especially keenly awaited after the disruption caused by the pandemic to both educational systems and the testing program of PISA itself.

1) Asian countries are leading the world in educational attainment – and it is not driven by wealth.

As Andreas Schleicher, the champion behind PISA, puts it – poor kids in China now outperform rich kids in America. China isn’t covered by this year’s PISA, but the top 5 performers in Maths and science are all East or South-East Asian countries (honourable mention for Ireland, the only non-Asian country in the top 5 for reading).

Indeed, once spending per pupil hits a reasonable level (roughly the expenditure of Greece or Lithuania), there is almost no relationship between spending and results. Expenditure looks much less important than what happens in those schools.

For example, while many Western countries have prioritised smaller class sizes (at huge expense), successful Asian approaches have instead prioritised releasing teachers’ time to spend on preparation outside the classroom and with parents. In Asian schools, the class sizes are sometimes double that of Western schools, but the teachers then have much more time to spend with parents and in one to one tuition with children, who they also get to know well. Meanwhile, teachers are encouraged and recognised for developing and using effective material – judged not least by the extent to which other teachers also download and use their content.

2) ‘Growth mindsets’ have now been identified as a major contributor to higher national level educational attainment – not just at individual level

Most readers of the BIT blog will know Carol Dweck’s famous work. Eleven year olds that are given feedback on a test highlighting their ‘good effort’ go on to outperform children who are told they are ‘smart’ on subsequent tests. Carol argues that highlighting effort creates a ‘growth mindset’ – the belief that how well you do relates to how hard you try. Armed with this mindset, children try harder when they face the inevitable challenges that arise in a learning process, just like people learn that aching muscles in the gym are a sign that you will get stronger.

In contrast, highlighting intelligence, or how smart a child is, can inadvertently create a ‘fixed mindset’. This implies that how well you do relates not to effort, but to natural ability, or perhaps your station in life. A fixed mindset can prompt a child to give up in the face of challenges or a bad test result.

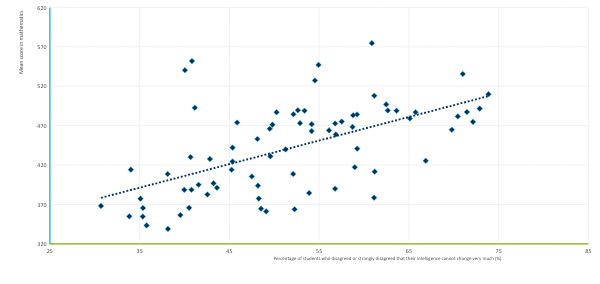

This is a new and striking result at national level. Schleicher and his team have shown that in high-performing – but not high spending – countries such as Estonia, kids are full of the belief that through their efforts, supported by their teachers, the sky’s the limit. In contrast, in countries like Albania, kids generally believe that how well they do depends on their intelligence, which is largely fixed. This belief drags down their effort and performance as a result. [They also note interesting exceptions too, like Hong Kong, where kids do academically well, but don’t have especially pronounced growth mindsets – so other factors do of course matter too!]

3) Digital distractions are pulling down educational performance

3) Digital distractions are pulling down educational performance

Parents and teachers have long suspected it, but the latest PISA shows that digital distractions are dragging down the educational performance of many kids.

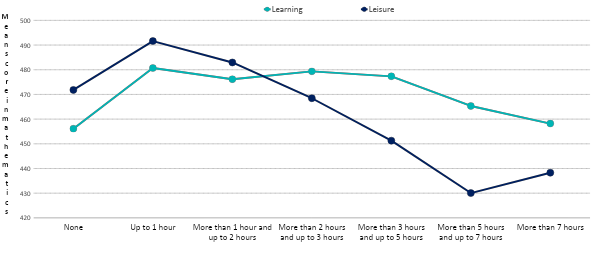

Importantly, the new OECD data also show it is how children use their phones and devices in schools that matters. Using digital devices for learning is fine. But using devices for leisure purposes negatively affects kids’ performance.

This evidence will surely reignite debates across countries about when and how children use digital devices in schools. Our only plea would be to make sure we involve young people themselves in shaping and owning these decisions!

Time spent on digital devices at school and mathematics performance [OECD, 2023]

Huge credit to Andreas and his team – as well as the hundreds of thousands of young people who took part in PISA to enable us to see these remarkable results.

We expect our kids to learn. It is imperative that we, and our educational systems also learn from these powerful and important new results.