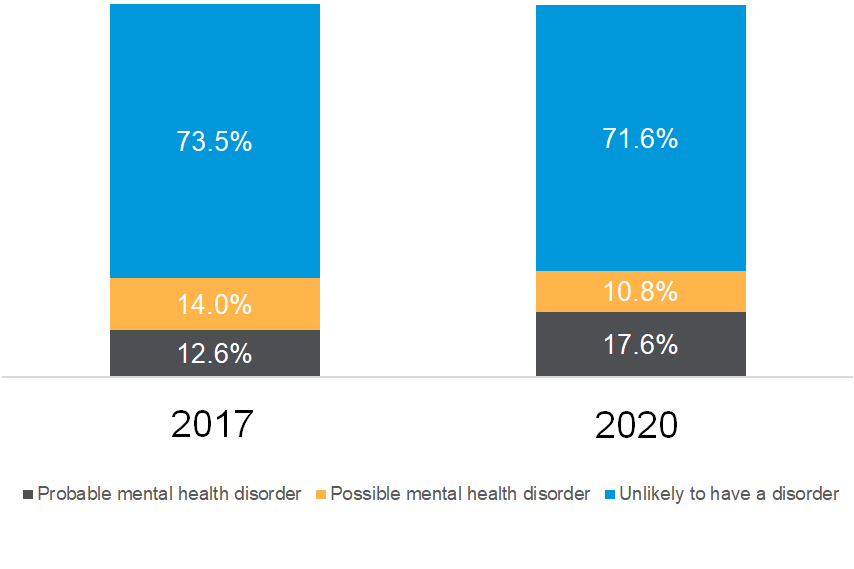

Even before the announcement of exam cancellations and a return to remote learning, teachers and students were facing major challenges. 10 months into the coronavirus pandemic, we’re beginning to understand just how big an impact it has had on young people’s mental wellbeing. The largest UK study so far suggests that the proportion of 11 – 16 year olds with a probable mental health disorder (indicated by a high score on a mental health questionnaire) has risen by 40% between 2017 and 2020 (from 12.6% to 17.6%). Data on change over time was not available for older teenagers, but in 2020 they had even higher rates of mental wellbeing problems – 20% of 17 to 22 year olds had a probable mental health disorder.

We also know that mental health is a priority for schools and colleges at the moment. In a survey last July, 81% of senior leaders rated their students’ mental health and wellbeing as one of their top priorities for the new term – the highest of any issue the researchers asked about.

But with time and resources stretched, and a new lockdown moving us back to remote learning, what can schools and colleges actually do to support student wellbeing? Over the past six months, we’ve teamed up with the Sixth Form Colleges Association to answer this question.

Our new guide for mental wellbeing in sixth form colleges suggests 12 strategies that colleges could try. We think that many of them will be relevant to secondary schools too.

All these ideas are low-cost and require limited time investment from teachers, who, we are keenly aware, are also adapting to the ‘new normal’. They are not meant to replace the intensive mental wellbeing support services that many colleges already provide, nor are they comprehensive solutions for students with serious mental health disorders. Instead, we hope they can supplement the things that colleges are already doing. Here are three strategies to consider:

1. Do mindfulness as a quick classroom activity

Mindfulness is the practice of deeply focusing on our thoughts and feelings in the present, to weaken the hold of negative thought patterns. In practice, what this means can vary from meditation, to quick breathing exercises, to taking the time to savour all the sensations of eating a raisin! Although the evidence from the academic literature is not totally clear cut, there are lots of promising studies showing that mindfulness can improve mood and reduce anxiety among children and young people.

Teachers could look to include a mindfulness activity at the beginning of a tutor group. Here’s a version of an evidence-based mindful breathing activity you could use:

- Find a relaxed, comfortable seated position.

- Take an exaggerated breath: deeply inhale through your nose (3 seconds),

- hold (2 seconds), and take a long exhale through your mouth (4 seconds).

- Repeat this cycle for a couple of minutes.

As you do this, your mind might start to wander. Just notice that your mind has wandered and then gently redirect your attention back to the breathing.

2. Experiment with gratitude exercises

Gratitude, in this context, means more than muttering “thanks” once in a while. It’s both a mindset and a practice of writing down thanks for the things you appreciate in life, even if they seem negligible. The idea is that developing a gratitude mindset allows us to focus on the positives in our lives more effectively and put setbacks into perspective. And there’s some academic evidence suggesting that written gratitude exercises can improve our wellbeing, at least in the short term.

Like mindfulness, some of these activities would be well suited to being a quick, regular class activity. Here’s one example. Ask students to spend a few minutes writing down three things that went well for them over the past week, and how they feel about them. These can be really small. Getting a compliment, finding a new TV show, or getting a good mark for a piece of work all count.

3. Choose messengers who will resonate with students

We’re more likely to take information on board if it comes from someone we respect, like, or who is similar to us. This suggests that schools and colleges should carefully consider who communicates information about mental health and wellbeing to students (for example, in email bulletins). Here are a couple of ideas for potential messengers:

- Head teachers or principals. In our interviews for this research, some students were concerned that their college didn’t take mental wellbeing seriously enough. Involving the leadership team might help to address this concern and communicate that your college isn’t just paying lip service to it.

- Influential students. There’s evidence that school-based anti-bullying campaigns are more effective when socially influential students run them. Schools and colleges could apply this insight by involving students in communicating mental wellbeing information. Perhaps a student council leader would be the right person for this, if you have one.

We hope that teachers and senior leaders find these ideas useful as they manage the beginning of the new term and the shift back to remote learning. If you would like to share your results from trying any of them out, or would be interested in a partnership, we would love to hear from you. Please get in touch via info@bi.team.

With thanks to Noni Csogor and Bill Watkin at the Sixth Form Colleges Association for their support, and to all the teachers and students who contributed for their ideas, time and advice for our research.