All women and girls deserve the power to make informed decisions about their health and futures. Unfortunately, we’re far from this reality. Globally, millions of people want to prevent or delay pregnancy, but a lack of awareness and access to sexual reproductive health (SRH) resources, social stigma and more prevents them from achieving this goal.

For example, in 2021 Kenya was ranked third in the world for teenage pregnancy. Each year, nearly two-thirds of the estimated 345,000 adolescent pregnancies are unintended—the vast majority (86%) occurring among people with unmet need for contraception. Behavioural science holds promise for helping adolescents turn intentions to avoid pregnancy into action.

For International Women’s Day, we’re sharing some of the lessons we’ve learned through our work in Kenya to encourage girls to access SRH services. Although our trials didn’t increase service uptake, our findings can shape future efforts to help young people take control of their reproductive futures with the aid of digital platforms.

A digital platform for Kenyan teens

From 2018 to 2022, BIT partnered with the Children Investment Fund Foundation and Triggerise, an innovation non-profit, to apply behavioural insights to the In Their Hands programme and increase uptake of SRH products and services.

We focused on Tiko, Triggerise’s digital platform, which provides girls aged 15-19 with access to free SRH services from private clinics. Between 2019 and 2021, more than 460,000 girls accessed services through the platform.

Barriers to taking up SRH services

Our work began by investigating the factors preventing girls from using Tiko to regularly take up SRH services. To pinpoint specific barriers, we conducted interviews and focus groups, utilising creative research methods such as body-mapping. Through these research activities, we identified the following barriers:

- Girls had low trust in SRH services, fueled by myths and a lack of accurate information about how contraceptives work.

- Girls thought contraceptive use among peers their same age was rare and mentioned that social stigma dampens their motivation to use products.

- Girls did not always understand the program’s financial incentives, called ‘Tiko miles’, which they earn for completing activities like visiting a health provider.

- While girls who enrol with the support of a community mobiliser benefit from face-to-face support, there is a gap in human reassurance and support for users who register online registrations.

Trials and results

Based on our findings from the initial research on barriers as well as evidence from previous interventions in this space, we designed two trials to help address these barriers and increase SRH service uptake. Specifically, we evaluated the impact of:

Sending behaviourally-informed messages: In a randomised controlled trial, our team tested two SMS flows against a control. The first used ‘mythbuster’ quizzes that gave recipients health information in an engaging format. The second urged girls to commit to a date and time for their next SRH appointment.

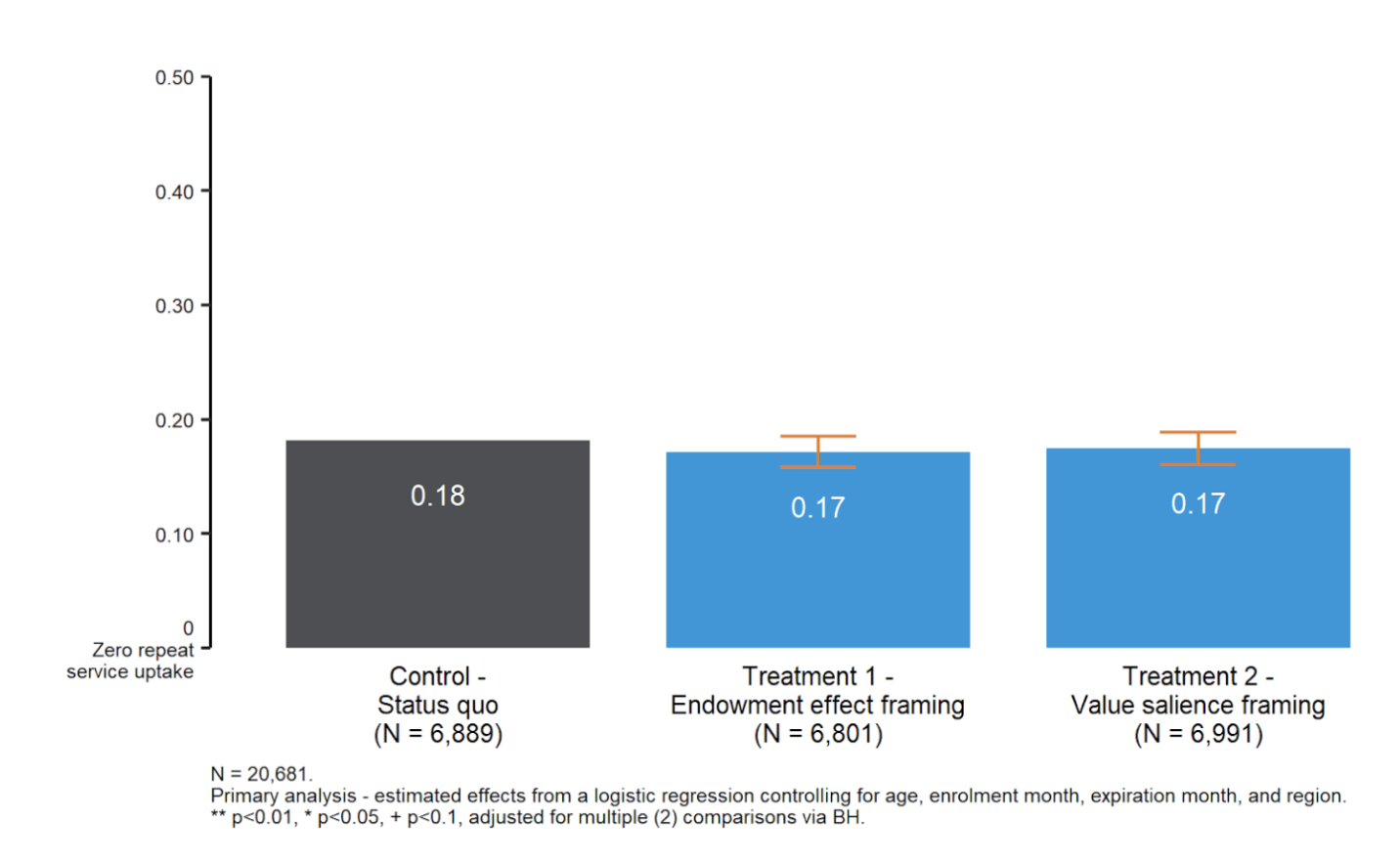

Testing incentives around SRH services: We tested an increased incentive amount for newly-enrolled girls who returned for an additional SRH service as well as two other incentive framings. The first framing aimed to address a barrier around newly-enrolled girls undervaluing incentives due to them not having used the Tiko miles before. To overcome this, we leveraged the endowment effect, instilling a sense of ownership of the rewards earned, (i.e. by letting users know the rewards are in their personal accounts). The second also sought to increase the value girls place on incentives by clarifying the monetary value of the rewards in Kenyan shillings.

Results: We didn’t find evidence that the SMS messages or changes in incentive amounts and framing increased SRH service uptake. Below we explore why we think this may be and how we hope to learn from this in future work.

We did not observe any significant effects of the framings on repeat use.

Lessons for future interventions

- We need to explore the role of SMS in SRH further. We think that SMS texts, even engaging ones, may be easily ignored (or missed) by adolescents. We observed that young Kenyans swap SIM cards to access cheaper mobile data, which may affect the integrity of data collected in digital interventions. Exploring other delivery methods (e.g., Whatsapp chatbots) may help messages break through in similar contexts.

- The human element in facilitating SRH uptake. Community mobilisers play a key role in helping girls overcome barriers to SRH services. They answered questions, countered myths, and helped users to understand what Tiko is and how it works. To scale this role, future interventions could test pre-recorded videos of mobilisers’ addressing common concerns, use social networks to maximise peer-to-peer referrals and consider creating a network of clinics with staff who offer assurances of SRH services. Finding effective alternatives to human mobilisers remains an essential goal in order to increase the scale and reach of Tiko across the country.

- Listen to the voices of those most impacted. The participatory process our team used to develop the interventions included co-designing the messages and testing with Triggerise staff and adolescent girls themselves. By incorporating the perspectives of people who would be most affected by the intervention in its development, we created a more inclusive and meaningful process.

- Many promising interventions haven’t been tried yet. Continuous conversations with adolescents and community mobilisers sparked reflection and great ideas for future trials with SRH programs. We see promise in testing group-based incentive structures, which have been shown to help people reach their goals around physical activity; and interventions that build self-efficacy (i.e. someone’s belief in their own ability to do something). Multiple studies show that self-efficacy is a predictor of condom use. It’s worth testing if self-efficacy can increase girls’ likelihood to use SRH services.

We hope these insights help inform future research to increase sexual and reproductive health access for women and girls worldwide. If you’d like to learn more about our work in Kenya or explore partnering with us on a similar topic, please contact us here.