Studying at university can be challenging at the best of times: students are often juggling financial stress, challenging course content, living or studying in a new city, and changes to their friendships and social support networks. The events of 2020 certainly do not appear to have helped: a recent survey of Australian university students found that 65% of students reported low or very low wellbeing.

We were interested in exploring how we could proactively improve student wellbeing and social support.

This is important because subjective wellbeing—which includes life satisfaction, social support, and emotional status or “affect”— is related to student success.* In fact, emotional health is often cited as a key reason students consider leaving their studies, whereas students with social support are more likely to stay in university.

We designed a text message intervention to encourage students to practice wellbeing-supporting behaviours

In collaboration with the Australian Department of Social Services (DSS) and Western Sydney University, we designed the “Wellbeing Project”— a five-week series of text messages that provided students with prompts and tips to practice behaviours that have been empirically shown to enhance wellbeing.

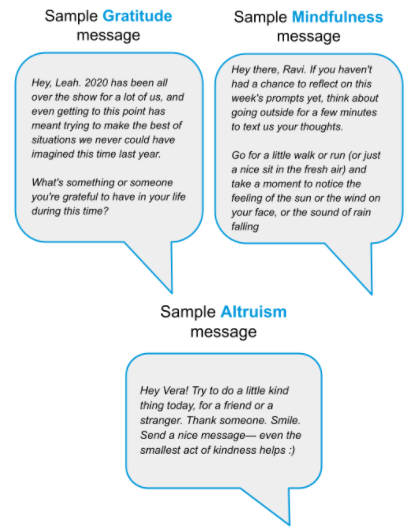

We designed the text prompts to encourage behaviours related to gratitude, altruism, and mindfulness (see sample messages below).

The Wellbeing Project boosted life satisfaction, social support, and community participation

We ran the Wellbeing Project for five weeks during the spring semester of 2020 (October-November 2020), and evaluated its effectiveness using a randomised-controlled trial (RCT) with 1,116 students, with half of the students receiving the new text messages and half receiving business as usual. Students in the treatment group received 3-5 text messages a week prompting them to practice a wellbeing-supporting behaviour, such as expressing gratitude to someone, doing something kind for someone, or practicing mindfulness. Students in the control group only received messages about completing two surveys: one halfway through the trial and one at the end. These surveys measured several contributing factors to wellbeing, including students’ life satisfaction (using the measures from the UK Office of National Statistics), social support, and how connected students felt to their communities.

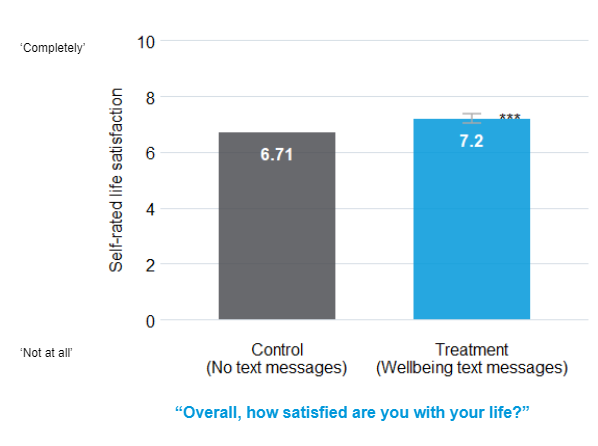

The intervention had a significant positive impact on life satisfaction. We saw an increase in life satisfaction of 0.49 units on the ONS scale. Without much context, this may not mean much to readers. However, this is about the same difference in average life satisfaction for someone who has an annual household income of $18,000, versus someone who has an annual household income of $27,000.

Students who received the wellbeing prompts reported a 7.3% increase in life satisfaction relative to students who did not

The group who received the messages also practiced and expressed gratitude to others in their lives more often, talked to people in their life that support them more often, and felt more connected with their community (compared to those who didn’t get the messages). These are positive outcomes that suggest the benefits of the intervention are not only seen in life satisfaction, but also in people’s daily lives and relationships with others.

Students liked the intervention, and felt that it enhanced their resilience during difficult periods

The surveys that we used showed us that the text messages increased students’ life satisfaction, but we were also interested in what the students thought about the messages, and how students would respond to them. We began to develop an understanding of this from the student responses to our surveys, and the text message prompts themselves. For example, we learnt that many students appreciated the reminders being sent to them throughout the week, and that it helped to keep things in perspective:

I really liked the reminder about what I wrote that I felt grateful for – sometimes when things are difficult I lose sight of the good things in my life so it really put some perspective back into my life and reminded me of what was important”

Several responses to the text messages indicated that students were struggling with stress and isolation on a daily basis. But, when we prompted them to reflect, many appreciated thinking about small things to be grateful for.

Today it rained, steady and beautiful. I am in a state right now, anxiety high, things going wrong, people around me at the brink of collapse; but to stand in the rain and breathe in that smell of wet earth, feel the drops hitting me and hear that calming sound of rain on concrete really helped.”

Even looking up at the sky every sunny day is my favourite thing during this lockdown period… Even if we’re not able to go out… The sky is still above us.”

This demonstrates that small nudges, such as text messages to reflect on the things students appreciate, have the potential to have large impacts on life satisfaction, resilience, and practice of wellbeing enhancing behaviours.

If you’d like to hear more about this trial, or how to scale this in your university, let us know by getting in contact!

The Wellbeing Project was part of the Strengthening Students’ Resilience program of work – a partnership between BIT and BETA (the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government) funded through the Australian Government Department of Social Services Try Test Learn fund. Visit www.dss.gov.au for more information

*In this blog we focus on life satisfaction as a proxy measure of wellbeing, but there are many components of wellbeing. We acknowledge that there’s lots of things that contribute to positive outcomes for students, but we’ve kept the discussion brief here.