The tragic triple homicide case in Nottingham has raised many questions about Valdo Calocane’s interactions with mental health services. The critical question is whether these senseless murders could have been prevented through better and earlier intervention.

This is the right question to ask, but if we want to understand how to prevent homicide in the future we need a much bigger sample than just one horrific case. We need to understand any systemic patterns. Unfortunately a seemingly simple question like “how many convicted murderers were known to social services?” is difficult to answer, because this data isn’t routinely collected by police forces.

Under existing law the police are only required to report the basic facts of a case, such as the gender and ethnicity of the victim. Some forces will collect more, but often only basic variables: just a single flag that says whether the case was mental health-related.

Getting the right data

Two years ago, we were funded by the London Violence Reduction Unit to try to address this gap. We worked with the Metropolitan Police to create a comprehensive framework capturing extensive details of homicide cases. We focused on contextual factors like the behaviour of the suspect leading up to the incident to understand the drivers of homicide.

Creating the framework

There are two big challenges when creating a coding framework like this:

- How to make sure the right data is captured If you decide in the future that you want to capture a new variable, or capture it in a different way, you will have to go back and add it for all the past cases (or, have insufficient data for a long time). So making sure you have the right variables, from the start is incredibly important.

- How to make sure data is coded consistently If two people were given the same case, you need them to code it in the same way: subjective data is difficult to interpret. If you’re recording what weapon was used this should be relatively simple. But for contextual factors, like whether the perpetrator was drunk, this can be much more complex. You also need the framework to be practical for different case types, from infanticide to domestic homicide to gang homicides.

To address the first challenge we reviewed the literature and spoke to homicide experts to understand what information was important in homicide research. This gave us an initial list of variables.

Two researchers then coded 50 case files covering a wide range of homicides. They did this iteratively, refining how variables were defined and any sub measures needed (for example, under method of homicide, researchers might suggest categories for weapon and type of injury) and regularly comparing how they had coded the same case file to ensure consistency.

What can the framework tell us?

In total, the framework contains over 200 variables, covering the victim(s) and suspect(s), the incident itself, the lead-up to the incident, and its aftermath. You can find the full report here.

Looking just at mental health for example, we recorded whether the suspect or victim had a confirmed mental health condition, a suspected condition, or none at all; what condition it was; whether they were prescribed medication, and whether they were still taking their medication. We also recorded whether they were known to mental health services, whether they had contact with them (in the past, or in the run-up to the homicide); and whether they had been sectioned. And we recorded their mental health during the incident itself, such as whether there was evidence of a psychotic episode.

Finally, we recorded whether mental health appeared to be a factor in the homicide. This is subjective but critical. Of the 29 cases where we identified mental health factors, we only saw it as a factor in the homicide for 11 of those cases. Just because somebody has depression and commits a homicide, it does not mean depression caused the homicide. That distinction is crucial.

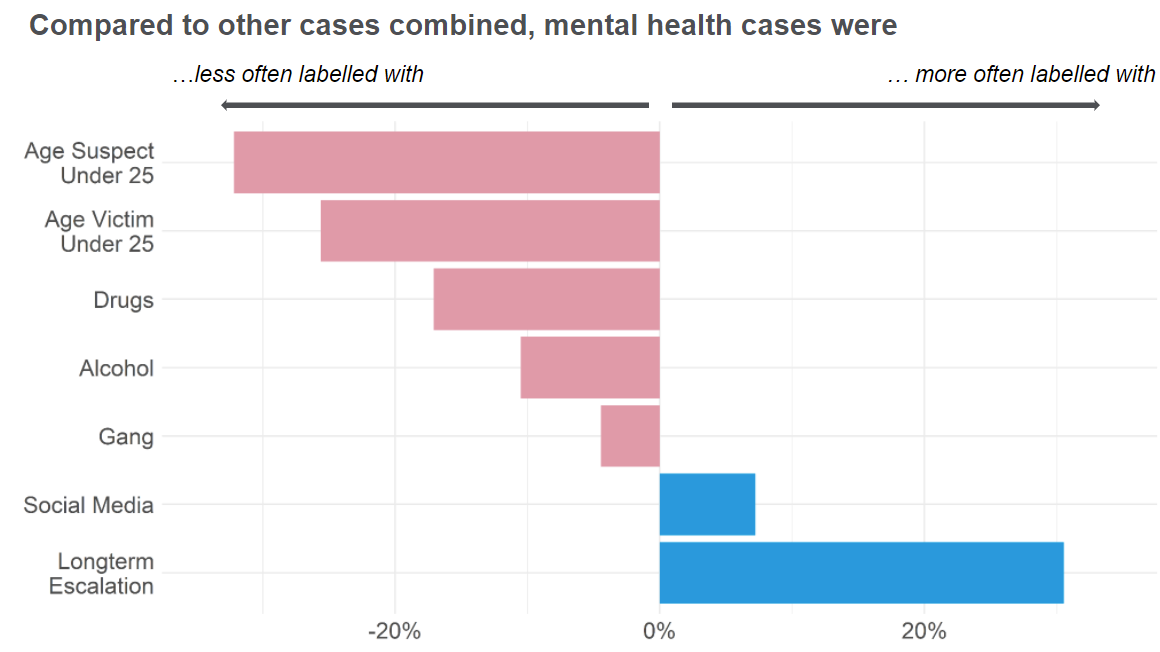

Example graph from our report

Why is this important?

The detail and nuance in the data is important for data analysis and our understanding of homicide. But it can also be personally important for victims’ families. Officers told us of the distress caused to families when their child’s case was labelled as ‘gang-related’ when their child was never involved in a gang. The code might be correct (for example, if they were mistaken for a member of another gang, or if the murderer had been put up to it by a gang), but without that nuance, families can feel that the classification insults the memory of their loved one.

But we also need to put these numbers in context. Mental health is a factor in many homicides, but that is not the same as saying most people with mental health conditions commit murder – we know that is not true. This is called survivorship bias: we only observe outcomes when an event occurs. If we want to understand whether mental health is a risk factor, we also need to understand the prevalence of mental health in the population as a whole. That requires better data across the board, not just within the police.

What next?

As with most data the power comes from a large representative sample. We’re currently working with the London Violence Reduction Unit and the Met to code historical cases and all homicides going forward. This will create what is arguably the richest dataset on homicide in the world. We should understand a lot more about how and where homicide occurs and provide a lot of information about opportunities to intervene.