In Australia, the tyranny of distance has led to a historical reliance on commuting by car. But small vehicles account for a total of 10% of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the emissions from these vehicles are as much as 40% higher than other countries. This comes in addition to the risk of increasing air pollution, and increasing congestion in cities.

While changes in working flexibility might ease some of the problems with car-based commuting, there is still a profound challenge for people who rely on transport to get to and from work. Historically, shifting transport mode is very difficult, as commuting is a strong default, and a very habitual behaviour. On top of this, private car travel has many advantages, including privacy, convenience, and flexibility, while public transport infrastructure is often found lacking. So, how do we shift people away from private car travel to more environmentally friendly alternatives, such as public transport?

One of the more blunt instruments we have in our behavioural science toolkit is financial incentives, or “hard nudges”. These have been somewhat successful at changing travel modes. For example in Copenhagen, a free month of travel on public transport significantly increased self-reported use of public transport both during the trial period, and five months later. Perhaps it’s a bit obvious to say that paying people to take public transport will make them take public transport. But the theory here is that if you can encourage some people to try public transport just once, they might overcome some of the existing prejudice they might have and realise it’s actually more convenient than they thought!

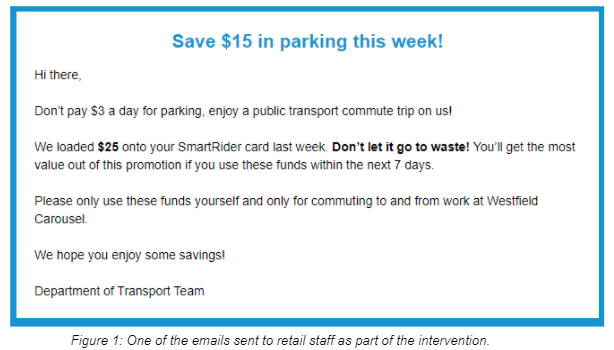

We worked with the Department of Transport in Western Australia to put this theory to the test, aiming to shift retail staff at a large shopping centre in Perth from commuting via car to public transport. We gave 134 staff at the shopping centre a free SmartRider card. For the next four weeks, at the start of each week, we loaded the card up to $25 worth of value. We also sent emails to staff each week (using different behaviourally-informed messages) to remind them that they could essentially travel for free, and they should try out their cards if they hadn’t already.

To see if this actually changed people’s commuting behaviour, we compared trips taken on these cards to those in a “waitlist” control group, who received cards but were told that they would be getting funds in the near future. We told the 101 staff in this control group that they could (and should) still use their cards on their own dime during this period. By comparing the treatment group with this control group, we essentially ran a randomised controlled trial, but while equitably providing funds to both groups.

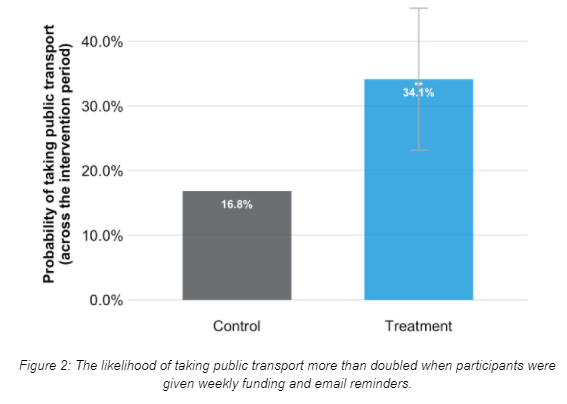

When we collected data from the SmartRider cards, we could see that the financial incentive and emails increased the likelihood of taking public transport. As shown in the graph below, staff were more than twice as likely to take public transport when they received weekly funding and email reminders.

It’s great that people were taking up this offer and using public transport, but what if these were people who would normally take public transport even if we didn’t fund their commute?

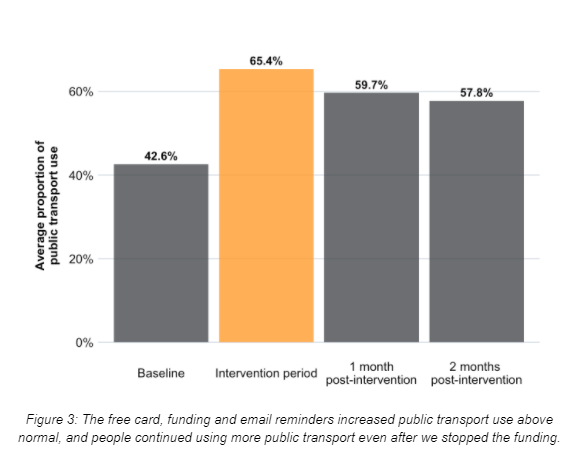

We don’t think this is the case, as we asked participants before, during, and after the funding period what proportion of trips to and from work they were taking public transport. The graph below shows that funding increased the proportion of trips taken compared to before the intervention. More importantly, we can also see that the proportion of trips taken using public transport remained higher than before the intervention even after the intervention had finished, suggesting that this had a lasting impact on behaviour – even when we weren’t paying for trips any more!

It’s important to emphasise that we don’t know how much longer this behaviour sticks around. At the very least, this shows that people are likely to use public transport if organisations like shopping centres or larger businesses subsidise it on an ongoing basis. At the very best, this trial shows that – in line with our theory – making it easy for people to experience public transport for themselves gives them the opportunity to realise that it can be better than driving to work.

[I have] never taken public transport to work in the last 7 years so this was a great way to test it out and I found it was actually not as bad as I had expected!”

The challenge to switch to more sustainable transport methods is not going away any time soon. Across the globe, we’ve been looking at other ways to change transport behaviour, including reducing car commuting in Canada, and encouraging EV uptake in the UK. If you have any ideas, or are keen to take up this challenge with us, get in touch!

This trial would not have been possible without the kind participation of the managers, staff and Centre management at the shopping centre, and advice and support from the Public Transport Authority, Western Australia.