Millions of deaths can be prevented each year if people spend 30 seconds of their day at the sink. Handwashing with soap has been estimated to prevent almost 1 in 3 incidents of gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses – a similar impact to chlorinating the water supply. Encouraging hand hygiene is therefore particularly important in transient settings such as Rohingya settlements or camps. This is why BRAC has installed thousands of handwashing stations (HWSs) in camps in Bangladesh, home to over a million displaced Rohingya nationals fleeing genocidal violence. And yet it is well-established in the literature and through BIT’s past work as part of the Hygiene Behaviour Change Coalition (HBCC) in Bangladesh that just building HWSs is not enough – usage of HWSs remains low unless we address behavioural barriers.

With the generous support of Reckitt Global Hygiene Institute (RGHI), BIT collaborated with the BRAC Social Innovation Lab (SIL) to encourage usage of HWSs among the Rohingya nationals in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh through developing BI-informed communication interventions that addressed behavioural barriers faced by the community.

One of the Rohingya camps at Cox’s Bazar

Cox’s Bazar is currently the site of the largest transient Rohingya settlement in the world. Over one million Rohingya nationals live in crowded, temporary shelters, with limited access to basic necessities. Many of these residents are vulnerable to disease, natural disasters and gang violence, while also facing limited education and employment opportunities.

A model hand washing station within the camps

Motivational factors such as inertia, cultural practices, and lack of understanding of consequences of poor hand hygiene can lead to low usage of HWSs. These factors are further amplified in crisis settings such as Rohingya camps due to lack of access and opportunity to use HWSs. At Cox’s Bazar, HWSs often fall into disrepair due to normal wear and tear but also frequent breakage and disappearance of parts, reducing the opportunity to use HWSs. Access can be dangerous for women and girls who fear using public HWSs, particularly at night due to the lack of electric lighting, owing to the constant threat of trafficking and gender based violence in the camps.

Given the importance of access and opportunity, at the start of April this year, BRAC ensured that all HWSs in the target camps were repaired to follow the current Rohingya Refugee Camp (RRC) approved design. BIT then co-designed interventions with BRAC including:

- replacing soap bars at the HWSs with bottles containing soapy water to make it easier to use soap and avoid the problem of people taking the soap bars home. This also made it easier to record usage levels of soap;

- distributing “Khutba” leaflets to imams who could use religious concepts from Islam to promote good hand hygiene during congregational prayers;

- conducting group discussions with local community leaders (e.g. religious leaders and school teachers) to share information on proper handwashing techniques; and,

- placing pictorial stickers around HWSs to act as an environmental cue for appropriate handwashing.

Stickers placed on HWSs

Imams with the Khutba guide

In combination, we hoped to overcome barriers to access, increase the motivation to wash hands by reference to the importance of cleanliness in Islam, and solve the lack of how-to knowledge through trusted local figures and guidance on the stations themselves.

Evaluating behaviour change in a complex and challenging context

We conducted a field trial in two camps from April to May 2023. The trial involved approximately 300 HWSs that were estimated to serve over 50,000 residents. During the trial, BRAC implemented a repair schedule for all the HWSs in the trial, and deployed interventions in the selected camps.

We used a novel approach to collect data. We partnered with Poket, a technology startup that configured a bespoke mobile data gathering app for data collection in the camps. The app allowed enumerators to operate more or less independently, collect data when offline and receive their pay in response to uploads. The app could record location and enable uploads of photos of HWS labels, to track where data was collected. The app also had a back-end data repository so we could check each submission for accuracy before accepting them.

Screen grab of Poket’s data collection app on an Android phone

Enumerators observed HWSs and recorded data using the app developed by Poket. Building on our experience from a similar handwashing project in Bangladesh, enumerators were also instructed to record usage of soap by measuring soap levels in the soapy water bottles at the beginning and end of their shifts.

Enumerator training

In spite of the robust features of Poket’s tools, we faced problems with data collection. Multiple events occurred during the trial period which made it difficult for enumerators to conduct their observations. Whilst we knew there would be entry restrictions during Ramadan, and that sporadic incidents of violence means it is sometimes not safe to enter the camps, there was also a series of unexpected natural disasters during our trial period. There was a cholera outbreak in one of the camps, as well as a heatwave in April, and Cyclone Mocha in May – all this just in the space of a few weeks.

The scale of the difficulties residents in these camps face is simply immense, and the fact that this is then compounded by climate chaos is hard to contemplate. Camp residents often experience information fatigue given the constant instructions on every aspect of their daily routine, such as when, where and how to receive food, everyday essentials and medicines, how to prevent and respond to outbreaks of cholera, diarrhoea and other diseases, as well as safety, health, and hygiene messages. For nudges to cut through this cacophony of information they must be clear, actionable and salient.

On top of all this, network/GPS connectivity issues within the camps made it difficult for the team to match submissions with HWS locations. Poket made extensive efforts to retrieve location data by reviewing the HWS images submitted by enumerators. However, most of the photos taken by enumerators did not display visible labels. Overall, although we attempted to prepare as best we could, the challenges to implementing support within the camps proved enormous – a tiny insight into just how difficult it is for these communities to get the support they need.

Despite these challenges, we were able to learn a lot about this incredibly complex context, thanks both to our preparations before implementation and hard work by BIT, BRAC and Poket during and after the trial was conducted.

Behaviour change is about more than communication

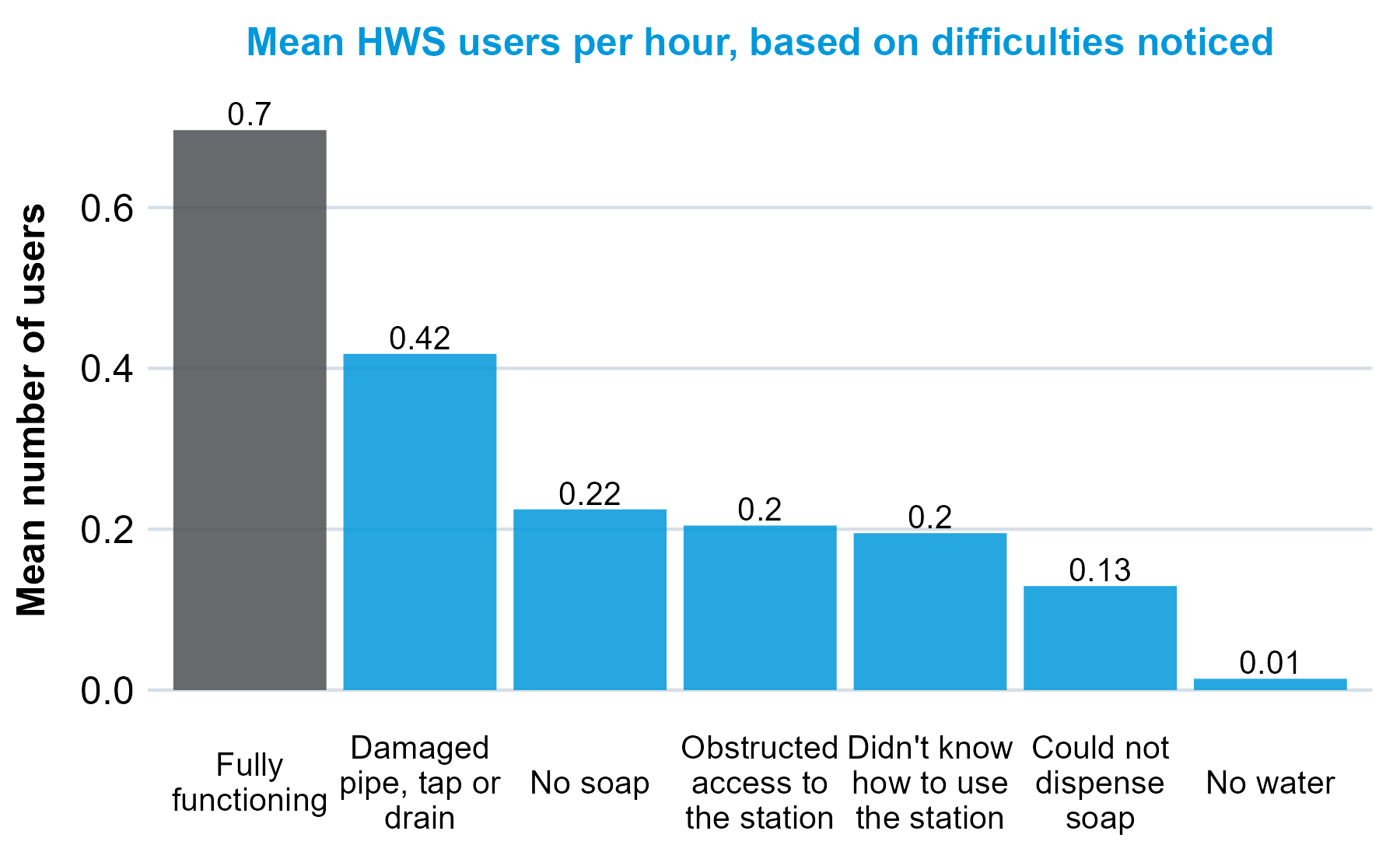

Our overwhelming conclusion from what we saw in our data was that individual behaviour change can only happen if there is a foundation of sustainable structures and systems. Despite continuous efforts to maintain HWSs, HWSs continued to fall into disrepair. HWS parts, such as the tap or even the entire water tank, regularly went missing. The proportion of observations recording functional HWSs with water fell from 18% at the start of the trial to 6% at the end of the trial. Unsurprisingly, people were much more likely to wash their hands if the HWS was fully functional, and it was most critical to have water and soap available.

Given this, we need to implement infrastructural hygiene interventions alongside behaviour change interventions. Based on our insights from the trial, we have three key recommendations to increase hand hygiene behaviours, particularly for displaced populations in temporary settlements:

- Encourage access to sustainable handwashing infrastructure. We need to build resilient handwashing infrastructure that cannot be easily damaged. This requires more investment in design and engineering for vulnerable populations. In addition, we need to expand access to handwashing infrastructure. This requires greater education on how to use HWSs, as well as safety measures for population subgroups (e.g. women) who may face threats of trafficking and violence. Simple measures such as adequate lighting, and calls to action for the community, could help.

- Encourage behaviours within the community that promote ownership and maintenance of handwashing infrastructure. Sustainable infrastructure is not just a matter of materials or designs, but also dependent on behaviours within the community (e.g. ‘borrowing’ bar soap, levels of carefulness when using HWSs). We need to expand our view of behaviour change, from individual handwashing behaviour alone to wider community behaviours surrounding ownership and maintenance of HWSs. For example, we could make it easy for people to take ownership, such as by having clear and simple mechanisms for individuals to report damaged HWSs. We could harness the endowment effect, by officially granting ownership to a specific local leader, or set of households, and allowing them to redecorate the station to reflect their ownership. With our previous engagement with BRAC on hand hygiene, it is worth noting that we spent six months together working on passing ownership and responsibility for HWSs to village leaders.

- Encourage other hand hygiene behaviours that are less reliant on infrastructure. The best hand hygiene practice is one that can actually be practised. Beyond handwashing, we could consider encouraging the usage of anti-bacterial hand sanitiser wipes. It is important to ensure that alternative hand hygiene practices are aligned with local cultural and religious practices. For instance, during COVID-19, sanitisers were sanctioned by Islamic religious leaders as permissible on health grounds making it acceptable to use among orthodox Muslim communities such as the Rohingyas. These could be distributed to each individual or household for personal use or placed in sturdy public dispensers. These might be less prone to wear-and-tear, though they may be more resource-intensive to provide. Promoting these alternative hand hygiene behaviours need not be mutually exclusive to handwashing – we could encourage individuals to make use of permanent HWSs (which are less likely to break than temporary ones), while using personal hand sanitisers when they are not close to a HWS.

This project highlighted the fact that handwashing behaviours are dependent on the structures and systems of specific settings. The core premise of a behavioural insights approach, and how it sometimes differs from social and behaviour change approaches, is the idea that, as Kahneman put it “environmental effects on behaviour are a lot stronger than most people expect”. To change behaviour, we need to change the environment.

—

| This project was a part of the Hygiene and Behaviour Change Coalition-2, an initiative supported by BRAC and Unilever R&D.

BIT’s involvement in the project was supported by the Reckitt Global Hygiene Institute (RGHI). |