Do you know how many variants SARS-CoV-2 has mutated into since the inception of the pandemic? You may have already stopped keeping track for one simple reason – the pandemic is no longer at the top of our minds. Yet back at the start of 2021, when the WHO issued the first emergency use of a COVID-19 vaccine, it was all everyone was talking about. You could be forgiven for thinking the pandemic was already a thing of the past, even as countries around the world continue to grapple with its effects. Perhaps the hardest part has been that the policy and behavioural challenges have been constantly evolving, just like the virus itself.

Like many other countries, the pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to vaccination systems and processes in Indonesia. Vaccines became first accessible to the general public in limited numbers in April 2021, and yet this progress was met with initial vaccine hesitancy. Added to this were logistical constraints, including storage, registration requirements, health worker shortages, and delivery challenges. Fast forward to mid-2022, the vaccination rate had become stagnant; and by 2023 the task of vaccinating the public had only become more challenging as people began questioning its necessity, asking, “buat apa vaksin lagi udah nggak butuh..” (“Why get vaccinated again? I don’t need it anymore”).

Vaccine access and hesitancy are as much behavioural challenges as they are policy challenges in Indonesia, and globally, which threaten to prolong the impact of the pandemic. The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) have been working to address this issue with national governments, donors, academics and service delivery agencies on the ground. In partnership with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), we collaborated with the Vaccine Data CoLab, ‘Aisyiyah, and Tulodo to view this problem from a behavioural lens. BIT led a project to motivate individuals to receive vaccinations in this new phase of the pandemic, or post-pandemic, where attention may be wavering but the threat remains.

Based on vaccination uptake data, we decided to focus on increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake among adults in Lumajang Regency, East Java. From a conventional policy angle, we might approach this issue based on the assumption that people are willing to get vaccinated when presented with the right information, so governments should provide accurate and up-to-date information about vaccine safety and efficacy. However, as in all projects at BIT, we acknowledge that to create effective policies, we must also understand the intriguing realm of human quirks and social context. We ran formative research including interviews and observations to embrace the story of real people making real decisions that may affect real lives in Lumajang.

What stopped people from getting a jab?

A perception that the pandemic has ended

More and more individuals believe that the pandemic has subsided, and hence perceive little need to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. With the diminishing intensity of communications on COVID-19 from the government and health professionals, albeit some strong pushes from the East Java government, people may self-licence themselves to be waived from getting vaccinated. This reflects our ‘optimism bias’ when it comes to, for instance, the probability of suffering from severe symptoms.

Competing priorities between work and vaccine schedule

If you were a farmer or a factory worker in these villages, making a decision to get vaccinated would not be so simple. The ramifications of taking ‘time off’ from work to get vaccinated could mean losing portions of your wage because the ‘nearest’ Puskesmas (community healthcare facilities) may be hours away. In other words, the opportunity cost of spending half a day getting vaccinated heightens as you can now get back to work.

Our approach to the problem

We decided to address these major barriers to vaccination. Whilst our thinking was informed by our past experience to increase vaccination both in high-income and low-middle-income countries, we had to be cognizant of the importance of local context for Indonesia. With this in mind, we crafted an intervention package that was not only effective but also more in tune with the stories of our target population, gathered through qualitative research. We wanted to:

1) Reduce practical barriers to getting vaccinated by providing longer opening hours, more local vaccination sites, and highlighting the existence of a walk-in service

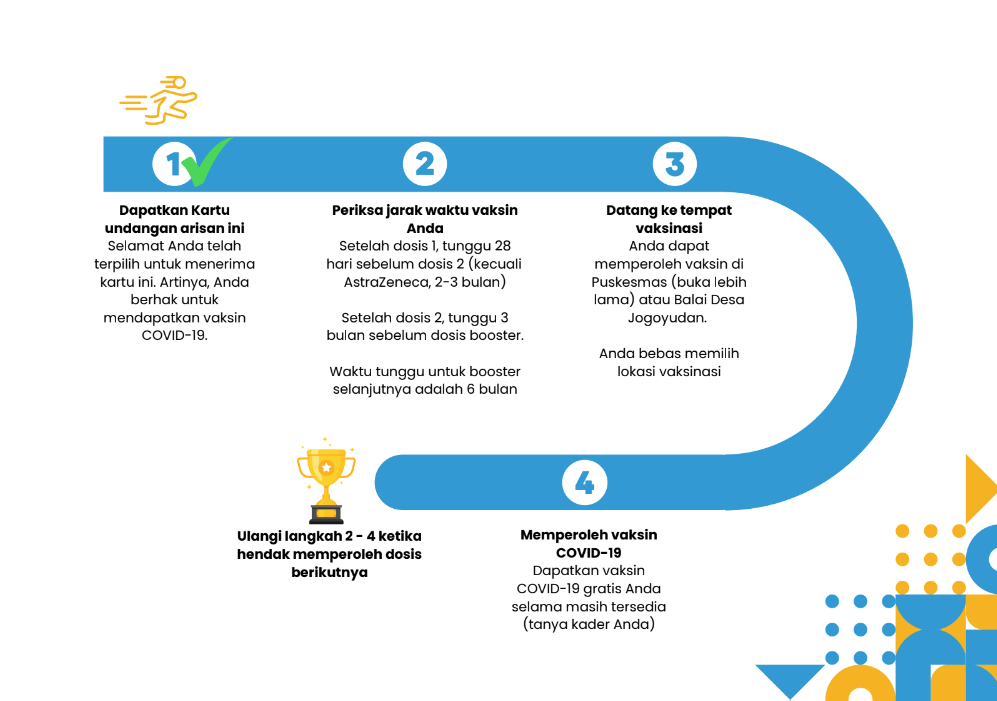

2) Create a tactile checklist – the ‘Adventure card’ – to visualise the user journey of getting vaccinated and self-signal the incremental progress towards receiving vaccines

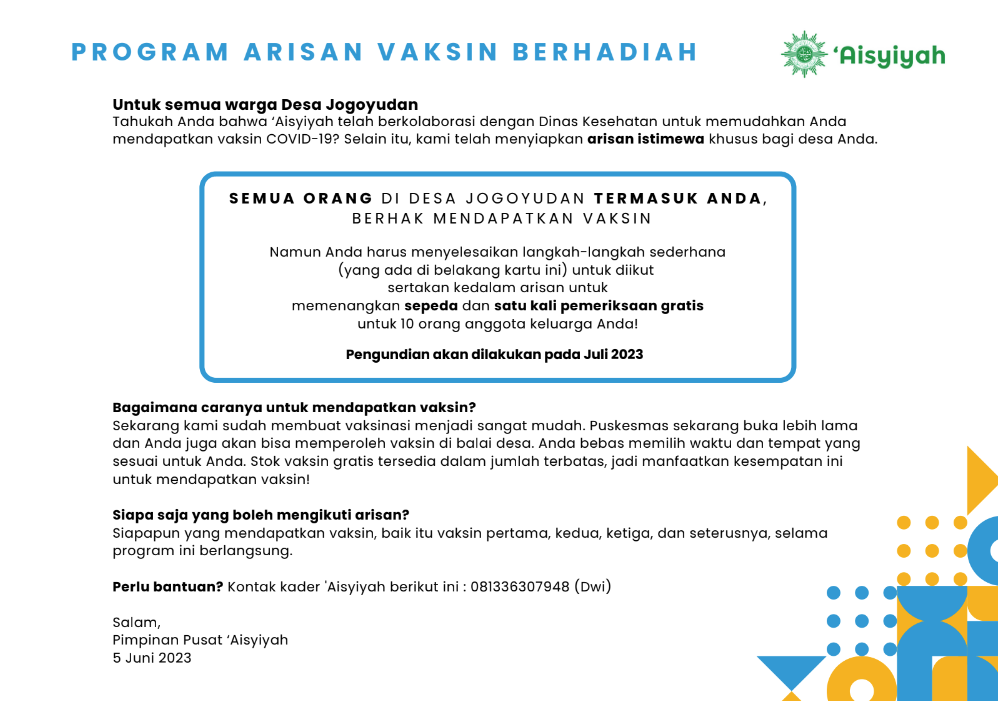

Figure 1. the Adventure card

3) Set up a lottery to win free medical check-ups for the whole family and a bicycle upon completing the Adventure card – see below one of our winners:

4) Disseminate communication material to encourage vaccine uptake via WhatsApp groups

Figure 2. One of the messages being sent during the intervention (translated to English).

5) Mobilise ‘Aisyiyah’s cadres (volunteers) to motivate and assist people to get vaccinated by facilitating social gatherings and direct community engagement

Rigorous testing of our intervention package

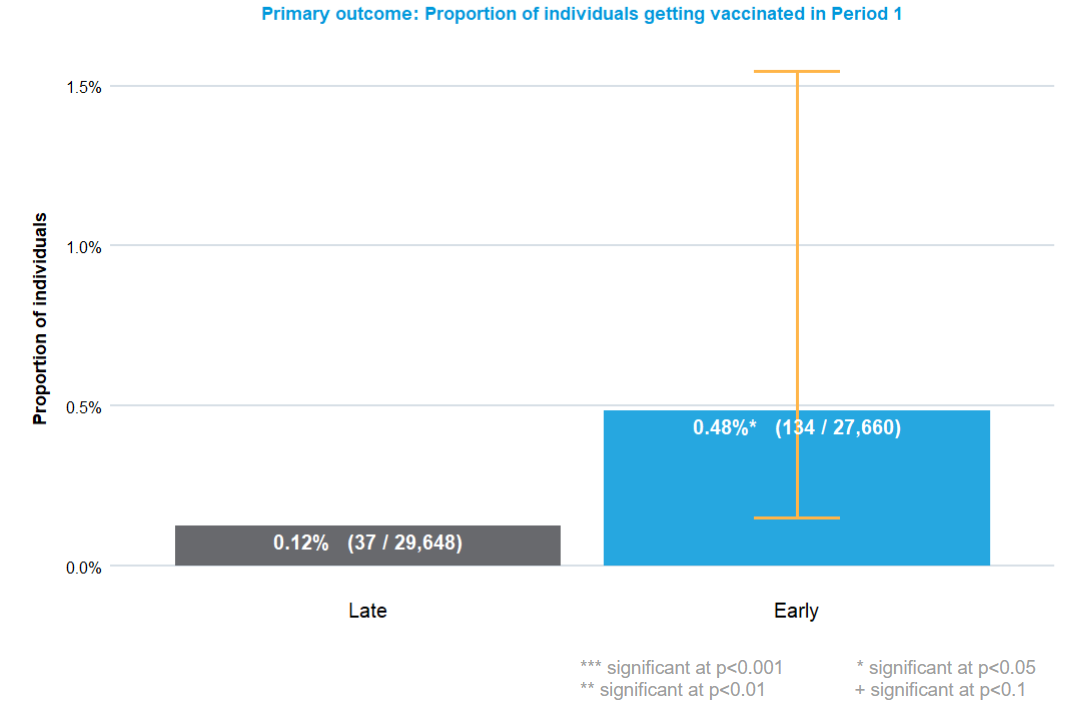

The intervention package was deployed in two phases using a waitlist control design. We found evidence that the intervention increased the proportion of eligible individuals getting vaccinated (0.48%) compared to our ‘Control’ group (0.12%). Notably, the treatment effect varied across villages as some villages had more vaccines being administered than others. One possible reason could be more conveniently located Puskesmas: for some villages, these are close by, for others, they are much further away.

Up to several weeks before the trial, very few individuals in these villages were going for vaccinations and boosters. Our intervention successfully vaccinated 633 individuals, using only vaccines that would have otherwise passed their use-by date. As well as generating this quantitative evidence on how to increase vaccinations, we also gathered enormous qualitative evidence to inform practice and policy by directly engaging with citizens, community leaders, health workers, and religious leaders, among many others.

This project is another testament to demonstrate the potential of behavioural insights to be applied beyond its WEIRD origins, but to do so we need to build from its fundamental principles. We know that some organisations, particularly in developing countries are facing incredible challenges trying to get health initiatives on their feet. Most do not have the time to review thousands of academic papers for their insights. While the findings we describe here may not be fully exhaustive, we believe it is accessible, evidence-based, and practical. Having said that, we want to distil three key takeaway messages:

- Access is key. Although we can promote vaccine uptake by making it easy, the effort to establish fundamental infrastructure to facilitate people to get vaccinated remains essential. We found that villages with more convenient access to Puskesmas had relatively more individuals getting vaccinated. This could mean that policymakers can get the most return out of their investment by combining infrastructure upgrades with behavioural insights because our findings show that provision alone may not be sufficient.

- The power of incentives. Incentives are a powerful tool to encourage vaccination, but must be carefully executed to mitigate unintended consequences. We anticipated that people might abandon the recommended dosing interval for the sake of chasing the reward – accordingly, we had built a countermeasure into the intervention design. One of the steps in the Adventure card required participants to wait for the dosing interval, which successfully impeded participants from circumventing this requirement. Overall, providing lottery-based incentives can be a more economical yet effective solution to help encourage vaccination in this context.

- Embedding behavioural lens into policy. Practitioners and policymakers seeking to change behaviour should consider using behavioural insights. This approach involves designing an intervention for a specific problem by understanding the behavioural barriers, and evaluating whether the intervention results in the intended behaviour change. Such an approach ensures that we are addressing the right barriers and help us learn not only what works but also what does not. Understanding how people actually behave in the real world is a worthwhile undertaking.

We carried out this work as part of the Vaccine Data CoLab, which improves vaccine uptake by strengthening health data systems and data-based decision-making processes. These findings from Indonesia underline the Vaccine Data CoLab’s wider learning, from its portfolios in Nigeria and Uganda, about the importance of working with local realities (from overworked health workers to unreliable power supply) and taking a systems approach which connects people and ideas at national, local, and global levels.

Countries like Indonesia, Nigeria and Uganda are trialling a variety of innovative approaches, enhancing their policy and legislative frameworks, and developing or implementing long-term plans for digitisation. However, for those interventions to be brought to life at the local level, holistic wrap-around support which considers all possible barriers to change, but which flexes to meet a diversity of contexts, is key. We see behavioural insights as a potential route to connect national decision-making with the local realities which drive vaccine behaviour, enhancing the effectiveness of nationally-driven vaccination programmes.

What’s next

We believe that these learnings can be transferred to neighbouring efforts to boost the overall uptake of child immunisation, or other health-related responses more broadly. In countries like Indonesia, such findings could be extremely valuable because immunisation remains one of the most effective public health interventions that is estimated to avert between 4 – 5 million deaths globally each year. If implemented on a national scale, our intervention would have resulted in an additional 84 million eligible individuals getting vaccinated compared to merely providing access to the vaccines alone. Given the availability of funding, we would love to run this intervention at a larger scale, working with the community and government to tackle other vaccine uptake challenges, like HPV. However, the ‘million dollar project’ would be not just to run a behavioural insights project, but work more with the Indonesian government. We want to build these behavioural insights approaches into the heart of health and healthcare policy and service design, integrating with the significant expertise and incredible determination we saw in our partners in the Indonesian healthcare system. If that sounds like what you want as well, please get in touch with us here.

The answer to the question at the beginning of this blog:

As of October 2023, the WHO assigns Greek labels for five variants of concern, namely Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 was identified to have thousands of distinct genome variants.