Of the almost 10,000 patients critically ill with COVID-19 in hospitals in England, Wales and Northern Ireland since the start of the outbreak in the UK, 33% were from Black, Asian, Mixed or Other ethnic minorities – even though people from these groups account for 14% of the population (excluding Scotland).

Why are ethnic minorities being hit harder by COVID-19 in the UK?

It may be because people from ethnic minorities are more likely to live in densely populated and economically deprived areas, and to work in key sectors of the economy, making it more likely that they will be exposed to the virus in the first place. Among those who do catch the virus, people from ethnic minorities may also be more likely to suffer more severely from it. Hypertension and diabetes, which can compound the health consequences of COVID-19, are more prevalent in several minority ethnic groups.

Racism may be a root cause of these differences between ethnic groups. After engaging with over 4,000 stakeholders and reviewing the wider literature, Public Health England found that racism, discrimination and structural disadvantage contribute to poorer health outcomes among ethnic minorities, both pre- and post-COVID-19. For example, stakeholders reported differential access, experiences and outcomes when interacting with health services. Outside of health, structural racism affects the broader life chances of ethnic minority groups in the UK, and the discrimination they experience in other areas can in turn undermine mental and physical health experiences and behaviours.

What we can learn from BIT’s experimental data

At BIT, we have run over 20 experiments looking at how people in the UK respond to messages about coronavirus. We re-analysed some of these with the aim of identifying suggestions that could help reduce the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities.

In the process, we found three things:

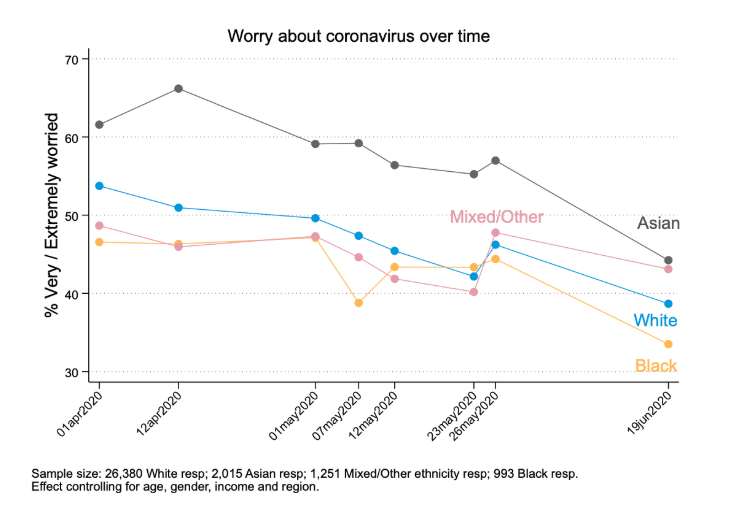

1. When transmission rates were higher, worry about coronavirus was significantly more prevalent among Asian respondents

Through to the end of May, Asian respondents in our sample were about 10 percentage points more likely to report being worried about coronavirus than other respondents (differences between other groups were not statistically significant). As the number of new coronavirus cases and deaths has declined, the differences between individuals of different ethnicities have narrowed somewhat, but these differences may re-emerge if infections resume spreading more rapidly.

Worry and fear are a natural response to danger. However, persistently high levels of stress are bad for our health. Making more resources available to help to manage coronavirus-related worry (and lowering barriers to access) may help reduce the psychological and physical consequences of these higher levels of stress.

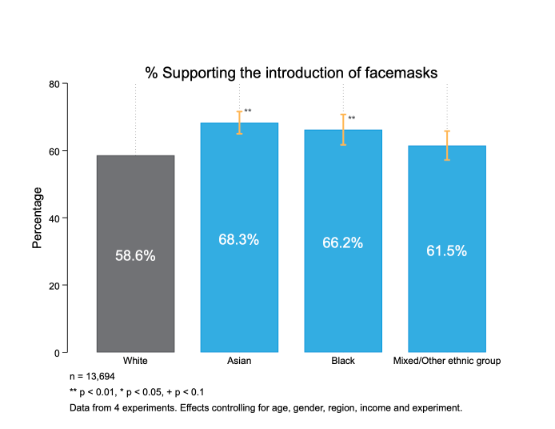

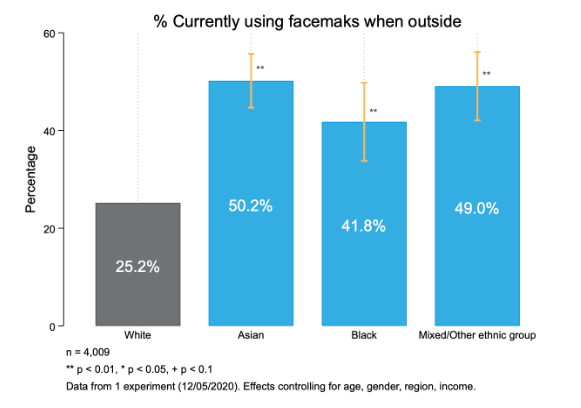

2. Ethnic minorities are substantially more likely to be using facemasks

In data collected in April and May, we found that Asian and Black respondents were more likely than White respondents to support mandating the use of facemasks in public. They were also substantially more likely than White respondents to wear facemasks, as of May 2020. While evidence mounts that widespread adoption of facemasks can reduce the spread of COVID-19, minority groups will continue to be disproportionately impacted unless adoption increases among all of us. Fortunately, the vast majority of UK residents say they are willing to use facemasks, even among groups that are less likely to be wearing them currently; policymakers must find ways to turn this positive intention into action.

3. Individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds may face circumstances that make it harder to strictly follow self-isolation guidance

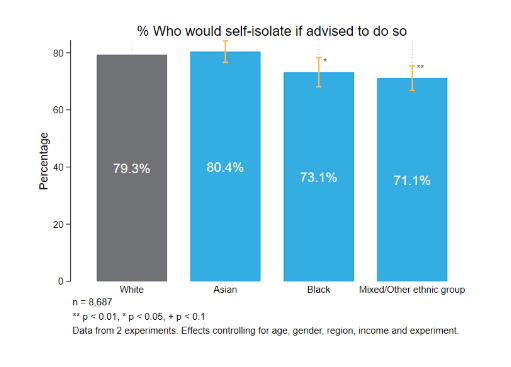

In late May we measured intentions to comply with NHS advice to self-isolate following contact with someone who had coronavirus. While 80% of respondents of Asian and White ethnicities said they would ‘definitely’ follow the advice, the proportion was somewhat lower among respondents of Black, Mixed and Other ethnicities. The most commonly reported barrier was the need to buy food, while the need to work and see family were mentioned more often by ethnic minority respondents than White respondents. We also found that individuals from Asian, Black and Mixed and Other ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely than White individuals to interpret the guidance as allowing trips outside the home to obtain food and other necessities, suggesting that safe alternatives to acquiring essentials are not sufficiently salient and accessible.

While financial and non-financial support is available for families who are self-isolating, these results suggest that more needs to be done. Existing support may need to be increased or made easier to access. Improving access of low-income communities to digital technologies (e.g. online shopping services) could also help.

What is the way forward?

Based on our analysis, we think that policy-makers should

- Make public health guidance and resources to help support people worried about coronavirus more salient and accessible to all parts of the population.

- Turn widespread willingness to wear face masks and coverings into a norm of widespread (and correct) use, to protect individuals who are more at risk of contracting COVID-19.

- Make it easier for people who need to self-isolate to do so, for example by increasing financial support and access to online services.

Of course we know that these policy changes do not come close to addressing the root causes of the disproportionate impact of coronavirus on ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, as part of our solidarity with Black Lives Matter and our commitment to antiracism, we at the Behavioral Insights Team are committed to sharing insights that may help the cause.