Lucía is tired. She has a full-time job, house work, and two young children. But getting them to school feels like its own job. This morning, Lucía’s 8-year old complains that he doesn’t feel like going while her toddler throws a tantrum, threatening to make her late for work.

“I don’t think Federico has missed a lot of classes this month… skipping today is probably okay. My mom can babysit him.” She knows how important education is for her child’s future, but thinks that missing a few days a month is fine.

Lucía’s story is common in Uruguay, which has one of the highest student absenteeism rates in Latin America despite efforts to improve attendance. Structural issues, like socioeconomic status, contribute to this problem, but people’s beliefs and behaviors also play a role. These can be influenced by applied behavioral science.

Reducing absenteeism by 6%

Ceibal’s Behavioral Science/Insights Lab and BIT made an impact on student absenteeism. A multi-component behavioral intervention reduced primary school absences by an average of 6%, equivalent to 1.7 days per academic year. In total, our intervention led to an additional 16,920 days of school attended.

Diagnosing behavioral barriers

Ceibal, Uruguay’s digital technology center for education innovation in public policy, partnered with BIT to boost primary school attendance. We started by analyzing attendance data and conducting in-depth qualitative research. We interviewed parents and teachers, which revealed many cognitive and behavioral barriers to absenteeism, including:

- Lack of knowledge: Parents don’t have a good sense of how much school is acceptable to miss or how many absences their children already had.

- Saliency and survivorship bias: Schools mostly focus on students with many consecutive absences. These cases are salient in administrators’ minds and trigger a protocol to check on the child and parents, overlooking other risky cases.

- Optimism bias: Parents think that their children don’t miss more classes than the average and consistently underestimate their total absences.

However, parents know that education is critical, and understand their responsibility in getting their kids to school.

Testing a letter, brochure, calendar, and chatbot

To address these barriers, Ceibal and BIT replicated a behavioral intervention that was successfully tested in US and UK schools. But we added a few innovations.

From March to December 2023, we ran a large-scale field experiment with a 3-arm clustered randomized controlled trial. 210 schools and families of 29,851 1st through 3rd grade students participated. The schools were in six departments, including Artigas and Montevideo, which have some of the highest absenteeism rates in Uruguay.

The treatment group received the full intervention:

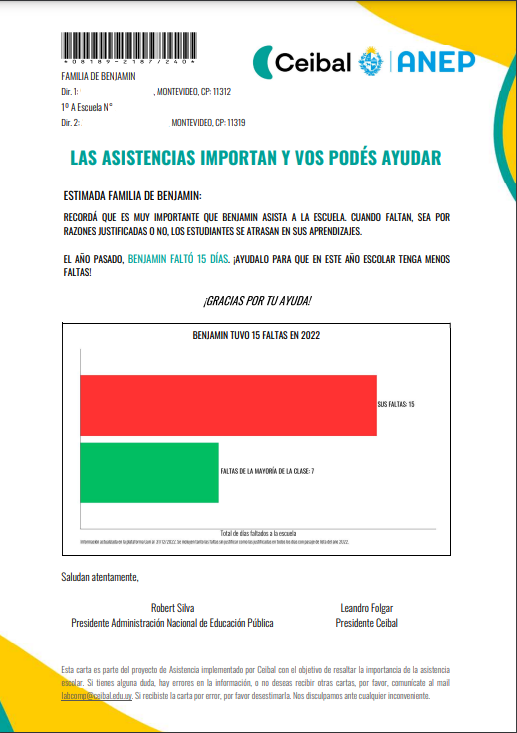

- Families were mailed three personalized letters throughout the school year informing them of their kids’ total absences (similar letters were found effective in other countries), plus

- A brochure about the importance of attending school, tips to improve attendance, and a commitment for parents to sign saying that they will send their children to school, along with

- A calendar to track missed school days with their children at home.

- We also created a WhatsApp chatbot that messaged teachers a monthly report of their students’ absences.

The calendar keeps school absences top-of-mind for parents and children as they mark attendance and missed days.

The personalized letter mailed to families.

The second treatment group included only teachers who received monthly reports via WhatsApp. We compared the results of the treatments to the control group, who didn’t get any communications.

The result: improved attendance at relatively low-cost

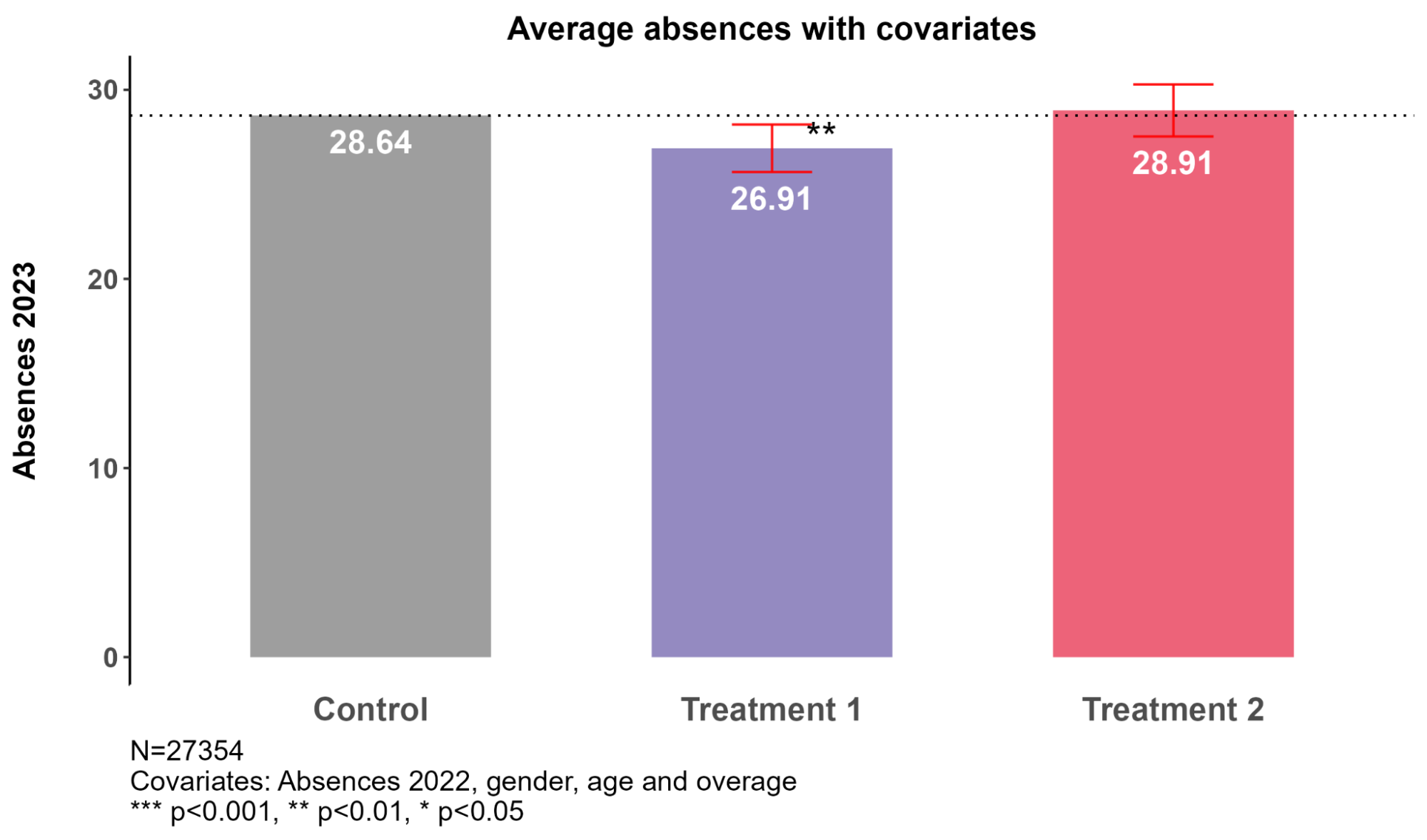

Students in the full treatment group saw a 6% reduction in absences, or 1.7 fewer missed school days, compared to the control group.

The full treatment had the biggest impact in schools serving under-resourced students, where absenteeism is typically higher. In these schools, it resulted in a 6.8% reduction in absences, or 2.2 fewer missed days.

Effects were also greater for those with average attendance levels. The majority of students fell into this group. They weren’t missing the most school, but didn’t have perfect attendance either. We saw a 7.6% reduction in absences for these students.

This finding is particularly relevant for applied behavioral science. Often, behavior change efforts focus on the “movable middle” rather than on people already performing the desired behavior (students with good attendance) or those who are very unlikely to change (students with the worst attendance). In latter cases, barriers to attendance are likely more structural in nature, which may require deeper strategies to address.

These improvements were more cost-effective compared to similar studies. The full treatment helped nearly 10,000 students boost their attendance. All together, they gained around 16,920 additional days of school at just USD $2.50 per day.

However, the treatment group of only teachers didn’t produce an effect on student absences. Teachers serve an important role, but simply raising their awareness of absences through monthly reports may not be enough.

From evidence to public policy: scaling the intervention nationwide

Ceibal and the National Administration of Public Education are planning to scale personalized letters to parents of at-risk 1st to 3rd grade students nationwide—nearly 50,000 students total. If successful, it could lead to 110,000 days of school attended that would be missed otherwise.

Our work together exemplifies the positive impact of behavioral science in government. This experiment was among the first that Ceibal’s behavioral insights unit conducted. In early 2023, with the Inter-American Development Bank’s support, Ceibal and BIT established this team’s structure and theory of change.

Drive change in your school system

We hope this success encourages other Latin American countries to replicate this study. Most behavioral science research has been done in WEIRD societies (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), which limits how generalizable the results are. BIT has done similar work in US preschools, for example.

This intervention’s impact in Uruguay gives us more confidence that personalized letters can increase student attendance in many different places around the world.

Facing similar struggles in your school system? Contact us here to explore applying behavioral insights to your challenges, from absenteeism to educational attainment.